Interview,

Wu Wei on Silk Baroque

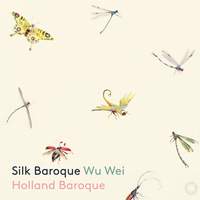

Cross-cultural concept albums are a relative rarity in the classical world, but when they do come along they’re often profoundly thought-provoking. One recent musical partnership which certainly fits this description is Silk Baroque, a collaboration between the acclaimed Dutch early-music ensemble Holland Baroque and leading sheng player Wu Wei, which was released on Pentatone earlier this summer.

Cross-cultural concept albums are a relative rarity in the classical world, but when they do come along they’re often profoundly thought-provoking. One recent musical partnership which certainly fits this description is Silk Baroque, a collaboration between the acclaimed Dutch early-music ensemble Holland Baroque and leading sheng player Wu Wei, which was released on Pentatone earlier this summer.

Unsurprisingly, the repertoire is highly varied, encompassing relatively intact arrangements of Baroque instrumental pieces, traditional Chinese melodies, and more free-form, improvisatory works. Wu Wei was kind enough to share some of his thoughts about this album, and about how he views the interaction between what appear at first glance to be two very distinct musical languages.

Wu Wei image credit: Liudmila Jeremies | Sheng image credit: Wouter Jansen | Translation & interpreting: Katharina Parczyk

This album breaks new musical ground in the combination of two very different musical cultures, but putting a traditional Chinese instrument into a Western Baroque context isn’t the most immediately obvious concept for an album. How did the idea for this collaboration first take shape?

I was lucky to meet Judith and Tineke Steenbrink, the founders of Holland Baroque and artistic directors of the SILK BAROQUE project. Their roots are in Baroque music, but they are very open to other musical eras and cultures. During our first meeting in Sanssouci in Potsdam, we immediately got along well with each other. Even then, they were already playing Chinese melodies on their Baroque instruments, just as I was already playing Baroque music on my Chinese instruments. It was a fortunate coincidence that we were able to combine our different backgrounds and thus discover new aspects of two worlds already known to us.

Furthermore, I don't see any separation between Chinese and Baroque musical culture. The sheng’s sound is very rich in overtones, but crystal-clear like the light, a golden shimmer in the overtone spectrum. So in one sense, the main theme of my instrument is the light. And to me Baroque music also has this silvery-white, golden sound. String instruments strung with gut strings and their shining, transparent sound have always particularly fascinated me. When the two qualities of light merge, a new, even more radiant, all-transparent sound quality is created. Both musical traditions search for this light, its different weights and depths, widths and heights, and it’s not limited to one identity: enthusiasm, momentum and light-heartedness, but also sadness, melancholy and thoughtfulness. It is a willingness to illuminate each other, to shine together, to complement each other and to share the beauty of light. The light also reflects our life. I am always looking for a light that is very positive.

My instrument’s history of approximately 3000 years is based on a philosophy in which something given by nature is brought into harmony. The Chinese character for “sheng” is 笙, meaning "harmony". The sheng’s task is to bring elements into harmony with each other through its sound – be it people with people, people with nature, or people and nature with the universe – and that is the instrument’s philosophy. Sometimes people lose sight of this element of harmony, and they either give it up entirely or fail to restore it when it falters. This even happens in some ensembles, and it can impact the sound. Thus, my historical instrument’s philosophy and task is to restore this kind of interpersonal harmony.

Holland Baroque remains musically curious, despite its highly specialised style, and seem enthusiastic to bring its radiant and clear sound world into a new context and to spread harmony – without any sense of this new context posing a threat to the Baroque idiom. We hope that this will communicate itself our audience just as positively.

For those of our readers who may not be closely familiar with the sheng, can you outline mechanics of the instrument and how it’s traditionally used?

The sheng is the world’s oldest free-reed instrument and among the oldest Chinese instruments. This mouth organ is not only the only wind instrument on which chords can be played, but also the only Asian instrument that inspired the Western world. It didn't come to Europe until the 17th century, but many European instrument builders were inspired by the free-reed sound production and its construction, leading to the invention of, among others, the harmonica, bandoneon and accordion. They form a family of instruments, all descended in some sense from the sheng.

In the sheng’s case, the reed is a hand-made metal strip which is mounted in a bamboo pipe and resonates at a certain pitch when air is blown through the pipe. To obtain the correct pitch, the length of the reed tongue must be adjusted exactly to that of the bamboo pipe. The pipes are all connected to the mouthpiece by a wind chest. In order to make the reed tongues vibrate, the grip hole of the corresponding bamboo pipe must be closed while blowing. A unique aspect of the sheng’s construction is that the very sensitive reed tongues are cut from its surrounding reed-plate, and therefore respond to both directions of airflow (blowing and drawing), without altering the tone.

The original form of the sheng has 17 pipes. My instrument is a modernized model with 37 pipes – 20 additional pipes have been added, to enable a diatonic instrument to play chromatically. The original 17 pipes are closed with the fingers, the other 20 pipes are closed with keys. Since the pipes are always open through the finger-hole and are only closed for sound production, a lot of air escapes through the pipes during playing, so a high volume of air is needed to produce the sound. For the higher range, additional resonance pipes are attached to my sheng, which support the middle range and enrich its overtone spectrum.

This modernisation was all done with respect to the instrument’s original form: the traditional construction with its 17 pipes is left unchanged “underneath”, and the extensions complement it. So I almost have two instruments in one: one traditional diatonic sheng with a range from g up to g’'' (G-4 to G-6), and one adapted to Western music.

A sheng’s sound always has its own character due to the composition of its overtone spectrum. On the one hand, the traditional Chinese understanding of musical harmony can make interaction with Western instruments more difficult. But equally, this spectrum can wonderfully expand and soften the sound of other instruments, especially in interaction with wind instruments.

Your talents aren’t limited to the haunting sound of the sheng; you’re also an accomplished Erhu player, and that’s an instrument that might fit in more easily with the sound of a Western early-music ensemble. Why did you decide to focus in on just the sheng?

I see it the other way around. I have played together with a Baroque ensemble, the Lautten Compagney, on the Erhu before. This is a string instrument with a bow technique very similar to the viola da gamba, but the sound is unmistakeably Chinese. The combination with Baroque music has to be handled very carefully. For this project I preferred to use an instrument that complements Baroque music, rather than imposing a new character on it, and I felt the sheng was more neutral and therefore more suitable for this.

The sheng shares certain qualities with Western instruments such as the harmonica – what makes its sound so distinctive?

I have already mentioned the special features of the sheng's construction and its effects on the sound spectrum. The harmonica is an instrument that calls to mind the blues, folk music or military styles. Most people like to think in clichés – particularly with the harmonica, whose sound has long been used to evoke very specific imagery. Of course I am also influenced by my own tradition, and I cultivate the Chinese musical culture through my instruments. But I see my task rather as using my musical language to enrich the Western sound-world, rather than imitating or reshaping it. It is not a case of imposing an attitude on something else, but of viewing it as a whole.

I almost feel this question is too narrowly formulated; the juxtaposition of these two sound-worlds shouldn’t be seen in competitive terms. I wouldn't even think of it in terms of a direct comparison. The task of any instrument is to look to the future, not just to establish one clichéd sound and adhere to it. Sometimes artistic risks are necessary to make this kind of progress; if you’re wary of things that are different or unfamiliar, you need to take the opportunity to explore and experience something new. The sheng is just as “serious” as the popular harmonica – and likewise, the harmonica is just as “serious” as the sheng. So I prefer to avoid these direct comparisons.

Alongside the improvisations and arrangements of Chinese folksongs, there are a number of baroque pieces that have been presented relatively „intact“. How much trial and error was there in creating these new versions? Were there some that you found just didn’t work, and had to be discarded?

I honestly didn't expect that all three Chinese Traditionals would be included in the album – I thought it might be a bit too much for a Baroque recording. But maybe it’s an intentional gesture by Holland Baroque, to give Chinese music a place as well, to appreciate it and not to hide it. We’ve also played these songs live and they were very well received by the audience, but I had been concerned that including them would affect the unity of the recording, and that we might have to discard some of them for that reason. So I would like to leave the answer to the listener.

For me it has been wonderful to experience the openness of Holland Baroque and the way they opened their music up to the influence of Chinese music. We certainly convinced the Chinese audiences of this – people were very appreciative when they heard Chinese music in this Baroque arrangement. Judith and Tineke’s arrangements were fantastic, too. Of course there is a lot of trial and error, but that is the nature of every learning process. Above all it is the attempt that is important, because it creates new possibilities and beginnings. So I would never call it an “error” as such, just a learning process – if you’re too concerned about “errors” then you run the risk of being prejudiced.

Do you worry that by taking the sheng out of natural habitat and building an album around the idea of its alienness and mysteriousness to Western years, you’re reinforcing questionable ideas about the „exotic“ Orient?

After one concert a composer came to me and said to me that she had been very surprised not to hear any Orientalism in our music. I don’t see anything mysterious about this myself; everyone has their own concept of beauty, be it flowers or a landscape or something else. The fact that I came across Baroque music by chance was a great stroke of luck, since its musical qualities lend themselves very well to being adapted to the Chinese traditions. And the curiosity about these two worlds, which seem so culturally opposite, is what makes it possible to bring them together into something that is, ultimately, unified. This unifying power is fundamentally the essence of music; it is multi-dimensional, not limited by nationality or other barriers. It is a language of the soul that transcends geography; regional identities don’t enter into it. We certainly shouldn’t limit ourselves to fixed reference-points like Shanghai or the Orient – the fact that we think in such compartmentalised terms is probably due to the way we’ve been trained and brought up.

Fundamentally, music is about the universal content behind the various musical forms, which can be brought out regardless of what tradition one uses to access it – it’s about the overarching wisdom which underpins all musical cultures and which can be brought into the light by performers. J. S. Bach, for example, opens up different dimensions, but we as humans can never truly say "we understand Bach", because our minds only allow us to understand a very compressed form of the intelligence that underlies the music.

Silk Baroque was released on Pentatone in June, and was described as 'a summer joy' by The Times.

Available Formats: SACD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC