Interview,

Alessandro Marangoni on Rossini

I’ve always rather envied Rossini’s approach to life/work balance – after composing nearly forty operas before his fortieth birthday (and amassing a small fortune in the process), he essentially retired from professional musical life after completing Guillaume Tell in 1829 and devoted himself to indulging his life-long enthusiasm for cooking and fine dining, eventually settling in Paris with his second wife Olympe Pélissier and hosting lavish entertainments at his country house in Passy. Though ill health necessitated a complete break from composition for some years, he eventually began writing again purely for the entertainment of himself and his many friends, and the final decade of his life was quite astonishingly prolific – the wryly-titled Péchés de vieillesse (or ‘sins of old age’) numbers 150 small-scale vocal, chamber and piano pieces, and just over a decade ago the Italian pianist Alessandro Marangoni embarked on a mission to record the piano works in their entirety for the first time.

I’ve always rather envied Rossini’s approach to life/work balance – after composing nearly forty operas before his fortieth birthday (and amassing a small fortune in the process), he essentially retired from professional musical life after completing Guillaume Tell in 1829 and devoted himself to indulging his life-long enthusiasm for cooking and fine dining, eventually settling in Paris with his second wife Olympe Pélissier and hosting lavish entertainments at his country house in Passy. Though ill health necessitated a complete break from composition for some years, he eventually began writing again purely for the entertainment of himself and his many friends, and the final decade of his life was quite astonishingly prolific – the wryly-titled Péchés de vieillesse (or ‘sins of old age’) numbers 150 small-scale vocal, chamber and piano pieces, and just over a decade ago the Italian pianist Alessandro Marangoni embarked on a mission to record the piano works in their entirety for the first time.

I spoke to Alessandro shortly after the release of the final volume last month about how the effects of this decades-long sabbatical play out in the Péchés, the technical demands of Rossini’s piano writing, and some of the many in-jokes which play out in the pieces which he composed with specific friends and house-guests in mind…

Rossini famously took a long sabbatical from composition before writing the majority of these works – do you see any evidence in any of these pieces that he’d stayed attuned to musical developments during his ‘time out’, particularly the influence of Verdi, Wagner, Liszt or Brahms? Or was he just concerned with having fun?

After Guillaume Tell Rossini retired from opera, but he remained at the centre of the musical world: he was rich, famous, and for the many musicians, intellectuals and artists who went to visit him in Paris he was like a saint or a god! In Péchés de vieillesse we see Rossini writing music purely for the joy of it, and because he simply couldn’t stop writing: his mind was continually teeming with new ideas, without any commercial purpose, which is a very different approach than in his theatrical period. He was of course influenced by the Romantic aesthetic and by composers like Chopin, Wagner and particularly Liszt, who went to Rossini’s house to play (and especially to play Rossini’s Péchés, too): the piano was Rossini’s new special confidant.

How obvious is it that these pieces were predominantly for private performance among friends rather than for the concert-hall? For instance, are there any examples of private jokes in the works, or of pieces that were written to appeal to a particular friend or acquaintance?

Initially Rossini didn’t want to publish these pieces, because his purpose was to write for himself and for his friends, and to give a musical testament to his beloved second wife Olympe Péllissier. He compiled an official catalogue of Péchés de vieillesse in fourteen volumes, but there are other pieces of this period that he didn’t fit in it: Rossini was able to write a new sketch or a little piece very quickly for a dinner with friends, or a meeting on Saturday afternoons when he invited people to his villa in Passy for the joy of playing chamber music together before a nice big dinner (Rossini also loved to “compose” menus!).

There are other works (sometimes just a few bars each) which include jokes or bizarre dedications: for example a little piece written to be transmitted with the pantelegraph invented by Caselli, or another in which the pianist must sing like a parrot, or the famous Petit Caprice in the style of Offenbach in which the performer must make the shape of horns with his hands [playing with only the index and little fingers], because Rossini thought that Offenbach brought bad luck! I also found some short manuscripts with dedications to some Mademoiselle or friends, and he also sometimes inserted his own sign to indicate that certain passages were to be sang by baritone or mezzo-soprano, with the accompaniment of the piano of course.

Rossini wrote for the Italian and Parisian stage throughout his operatic career – do the piano works contain a similar mixture of French and Italian influences?

L’innocence Italienne, le candeur francoise is the title of a piece taken from Album pour les enfants adolescents: with great irony Rossini highlights the differences between Italy and France, and the two souls were combined in the composer’s life and in his music. In his Péchés de viellesse we can find the sunniness, the beautiful melodies, the love for bel canto that are typical of Italian music, as well as many reminders of his own Italian operas. But we can also pick up on the key features of French music of that period, in particular its experimentation with harmonies and tone-colours.

Much has been written about Rossini’s immense skill in writing for the voice – is his writing for piano equally idiomatic, and what does it tell us about his own strengths as a pianist?

Rossini wrote very well for the piano, but that’s not to say that his music isn’t difficult to play! He had a consummate knowledge of piano technique and explored all the possibilities of the keyboard. His writing is quite often transcendental: he uses a lot of octaves (Liszt-style), uncomfortable leaps around the keyboard, tremendously difficult fast passage-work, octave glissandi etc. He considered himself a “fourth-rate pianist” but of course you need “first-rate skills” skills to play his pieces well! We know that Rossini played his own music at home with friends: perhaps they stuck to the easier pieces, but he himself was used to practising Bach and Clementi at the piano every day!

Do you hear any obvious echoes of Rossini’s operatic writing in these pieces, or do you they occupy a completely different space?

I think there are some operatic echoes in terms of themes and even construction, but in Péchés de vieillesse Rossini is a chamber music composer tout court. Sometimes he was making fun of himself with quotations of themes from his own operas, so I think there is definitely a conscious desire to distance himself from that world, but we could do a long psychoanalytic essay about this…!

Finally, what drew you to this repertoire in the first place? As the booklet-notes for the first volume state, Rossini’s piano music was more or less neglected throughout the twentieth century…

When I was very young, I loved to improvise variations on 'Dal tuo stellato soglio' from Rossini's Moïse: my love for his music started early, but it's only during these last few years that I've had the opportunity to get to know Péchés de vieillesse better. Maria Tipo, my piano teacher, introduced me to a couple of pieces and I wanted to know more: it was real a lightning-bolt! My work for Naxos is indeed the first complete recording in the discography. I made several research-trips around Europe: I have to thank Fondazione Rossini in Pesaro and especially some researchers and collectors, such as Reto Müller, Sergio Ragni, Bruno Cagli and Philip Gossett who gave me some manuscripts. I also found some interesting unpublished works in a library in Brussels.

I believe that if you want to know Rossini well, you have to know his Péchés: they are a very important part of his creativity, and are essential to complete the vision we can have about this incredible man and composer. But there is also an other important motivation to listen to them: many aspects of Rossini's piano music anticipate the twentieth century, and knowing it helps us towards a better understanding of composers as diverse as Satie, Milhaud, Shostakovich and even Stravinsky. Rossini seems to have had an almost uncanny awareness of the music of the future.

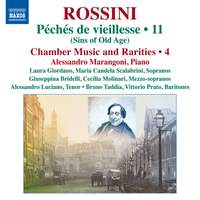

The final volume of Alessandro Marangoni's survey of Rossini's complete piano music was released on Naxos last month.

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC