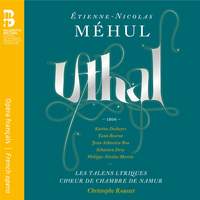

Recording of the Week,

Christophe Rousset conducts Étienne Méhul's rarely-heard opera, Uthal

‘Absolutely no idea, but I’m going with Meyerbeer’; ‘one of those Wagner or Berlioz orchestrations of Gluck?’; ‘like some sort of musical face-swap between Beethoven and French Rossini’. I’ve been harassing colleagues and musician friends over the past few days by asking them to ‘blind-taste’ my Disc of the Week, and the answers (excluding ‘Go away, I’m wrestling with my sales-figures’ and ‘I really can’t see this taking off as a pub-quiz round’) bear witness to the music’s weird and rather wonderful hybridity. Unsurprisingly, no-one guessed Étienne Méhul – the French composer has been little more than a footnote in musical history for far too long, but the bicentenary of his death this October looks set to kick-start a reawakening of interest in works which often blaze with revolutionary fervour and vivid, imaginative orchestration.

Until a couple of weeks ago my knowledge of him was limited to La Chasse du Jeune Henri, a favourite of Sir Thomas Beecham (possibly the last great champion of Méhul in this country), but a marvellous showcase for the composer in London last Friday alongside this new release of his one-act opera Uthal have made me ravenous for more.

Premiered in 1806, Uthal tells the tale of the ageing, Lear-like Scottish chieftain Larmor facing down rebellion from his hot-headed son-in law (who gives the opera its name) - but much of the piece’s emotional weight is centred on Larmor’s daughter Malvina as she wrestles with her duty to both husband and father, sung with style and fierce commitment by the French mezzo Karine Deshayes (her recent Rossini disc is well worth checking out if you’ve not come across her before). It’s set in the Scottish Highlands, but the musical landscape is distinctly wilder and woollier than that of Donizetti and Rossini’s Walter Scott operas: the electrifying opening storm, depicting Malvina’s nocturnal flight to her father through forests, crags and glens, has more in common with the storm in Berlioz’s Les troyens than the rather more sedate tempests that crop up so often in bel canto works.

In the hands of Christophe Rousset, it (and indeed everything that follows) simply crackles with energy, particularly in the incisive, turbulent string-writing: Méhul’s great imaginative coup in this work was to exclude violins altogether and instead use divisi violas to conjure up the Gothic ‘blasted heath’ and dark psychological terrain of his subject-matter. (The composer André Grétry remarked rather bitchily after an early performance that he ‘would give a louis d’or for the sound of an E-string’ but thanks to Rousset’s advocacy and balance - and to Méhul’s judicious use of upper woodwinds in particular - I never felt that the sonorities outstayed their welcome, though perhaps it helps here that Uthal clocks in at just an hour, and is punctuated with substantial sections of dialogue rather than recitative).

There are other striking innovations in the orchestration, such as the liberal use of the harp alongside the luminous four-part writing for the bards-in-residence who soothe and serenade Malvina in her torment (their lullaby was sung at Méhul’s funeral, and for my money yields nothing to Berlioz’s ‘Shepherds’ Farewell’ in its hushed beauty) and the eerie sul ponticello solo cello which accompanies Uthal’s opening scene (sung with plenty of Byronic Sturm und Drang, if one can say that about French music, by Yann Beuron) and sounds so uncanny that my colleague wondered whether it was actually an accordion!

In terms of the vocal writing, Méhul is primarily concerned with combining beauty of line and psychological drama rather than with pyrotechnic display – indeed, some of the libretto’s most emotive passages are spoken rather than sung, which could feel like short shrift were it not for the investment and energy of the Francophone cast. And the final hymn to reconciliation put me irresistibly in mind of Fidelio, which Beethoven was working on at the very same time. All in all, this lovingly and lavishly documented new set makes a strong case for a reappraisal of a composer once described as ‘The First Romantic’, and I for one will be actively seeking out more of him.

Karine Deshayes (Malvina), Yann Beuron (Uthal), Jean-Sébastien Bou (Larmor), Sébastien Droy (Ullin), Les Talens Lyriques, Christophe Rousset

Available Formats: CD + Book, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC