Interview,

Randall Scotting on Senesino

Best known today as the creator of heroic Handel roles such as Giulio Cesare, Orlando and Bertarido in Rodelinda, the Italian alto castrato Francesco Bernardi (aka 'Il Senesino') has inspired all-Handel recital-discs from artists including Drew Minter and Marijana Mijanović - but a new project from American countertenor and scholar Randall Scotting with the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment (released on Signum this Friday) takes a road less travelled, exploring music written for the star singer by composers including Bononcini, Ariosti, Orlandini, and the virtually unknown Giovanni Antonio Giaj.

Best known today as the creator of heroic Handel roles such as Giulio Cesare, Orlando and Bertarido in Rodelinda, the Italian alto castrato Francesco Bernardi (aka 'Il Senesino') has inspired all-Handel recital-discs from artists including Drew Minter and Marijana Mijanović - but a new project from American countertenor and scholar Randall Scotting with the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment (released on Signum this Friday) takes a road less travelled, exploring music written for the star singer by composers including Bononcini, Ariosti, Orlandini, and the virtually unknown Giovanni Antonio Giaj.

Randall spoke to me over Zoom last month about how the album grew from his doctoral research on Senesino's long and often tempestuous career, the insights which the music here provides into the castrato's remarkable vocal qualities and how they evolved (and eventually declined) over the course of his life, and some of the fascinating new repertoire which he unearthed along the way...

What sparked your interest in Senesino, and at what point did that transition into a PhD?

I’d been singing several of the roles Handel composed for him, like Giulio Cesare and Orlando, and they were such a great fit for me vocally and dramatically that I became curious about other operas that had been written for him. During a block of singing work a few years ago I found myself alone in Germany in the middle of winter with some time on my hands, so I started putting together a spreadsheet…First it was twelve roles, then it was twenty, and eventually I ended up with 114 operas that I know that he sang in - then I realised that if I wanted to take things further I needed the structure of a PhD programme that would also give me access to the archives.

It also struck me that although Senesino was super-famous during his lifetime, nobody had ever really delved into his background: singers today might recognise the name, but relatively little is known about him and I just thought that we needed to connect the dots. I started looking at what people said about his style of performing: the ornaments he excelled at, the way that he could execute a messa di voce and that sort of thing. That was one aspect of it, but I was also interested in how he built his reputation very consciously in various places throughout his career.

And then of course there was the repertoire itself: a large part of the PhD was digging up this music and creating editions. I absolutely loved doing it, and there was always something like this album in mind as an end-goal when I started my PhD research: because those Handel roles by had suited me so well, I knew that (at least theoretically) I should be able to sing whatever I found by these other amazing, but unknown composers.

Did you find that other composers explore elements of his voice that we don’t necessarily see in Handel?

Indeed. Handel wrote thirteen roles for him in London, and now that there’s been so much Handel scholarship and performances of his music, I felt like the door was open to start exploring at everything else… It was especially fascinating to look at Bononcini, who was composing for Senesino at the same time as Handel in London but was doing different things: he wrote in a much lower range for Senesino (maybe a third lower than Handel ever did), and also used the lower voice in a different way. With Handel it’s a gentle dipping in-and-out of the low range rather than a feature, whereas Bononcini would really sink him in the basement for extended passages - Senesino obviously had this strong chest voice which Bononcini wasn’t afraid to utilise, but perhaps Handel didn’t like that part of his voice so much?

Actually, Bononcini just used more of his range overall: as well as a bunch of low As there are notated top Gs, far higher than anything Handel ever composed for Senesino. There’s also an aria by Orlandini on the disc that uses an ornament called a martellato, which is repeating the same pitch in quick succession – Faustina [Bordoni] was famous for it, but this is the only place where it crops up in Senesino’s entire repertoire…I did a bit of research and it turns out that Senesino was performing in this opera with Faustina in 1729 in Venice; my theory is that he wanted to prove that he could do everything she could do, so he insisted on including this particular ornament. He never wanted to be outdone! Things like that became quite fascinating for me as a singer; to honour and know about all sides of this performer really influenced my interpretations of his music.

Apart from the music itself, what were your main primary sources?

There are so many. I recently came across a fascinating reference in a collection at the Yale archives in the Horace Walpole collection – it dates from a couple years after Senesino passed away, and discusses his later life when he wasn’t doing so well…He left the stage in 1739 and died twenty years later, and those last two decades of his life were full of turmoil and conflict with his family: issues about who was worthy to inherit his fortune and so on. The source mentions the fact that he basically wasn’t allowed to be around polite company anymore!

The major vocal treatises outlining good singing practice are also important sources for understanding his voice and why people revered him so much, because they give a lot of time-specific examples: Giovanni Battista Mancini’s Pensieri e riflessioni pratiche sopra il canto figurato (1774) mentions Farinelli’s capabilities and his particular strengths, and Pier Francesco Tosi’s Observations on the Florid Song (1723) mentions Faustina. Senesino performed with both of those singers and these mentions of their singing become quite valuable when I’m looking at what’s on the page for Senesino, because it helps you to put it all in context and understand what other people were doing.

You mentioned the rivalry with Faustina - how much do we know about his relationships with other castrati?

He and Farinelli actually sang together, in the 1730s. After Senesino left Handel’s Royal Academy of Music, he founded an opposing company called The Opera of the Nobility and they brought in Porpora as the main composer who oversaw everything musically; that coincided with Farinelli finally coming to London, and he ended up singing with Senesino’s company rather than Handel’s. Who knows how accurate these things are, but there’s a famous anecdote about how Senesino broke character and gave Farinelli a hug on stage because he was so moved by what he could do. If those accounts are accurate, then Senesino definitely knew that Farinelli was an amazing talent and couldn’t help but acknowledge it.

Later in life he didn’t like to be compared to any other castrati –Farinelli is one of two that he mentions, along with Carestini, saying ‘OK, you can go ahead and put me in a league with them but everybody else is basically garbage!’. That’s where he was at the end of his career, and it really shows how he felt about himself and his performing: he seems to have deluded himself that he was still this reigning primo uomo who could do anything, even though he was obviously declining in terms of his abilities.

And he had a fairly long career compared to other castrati…

Yes, unusually long. The main part of Farinelli’s career only lasted about a decade; then he went to Spain and sang privately for the King of Spain and ran an opera-company and did all sorts of other civic things - overseeing how towns were laid out and that kind of stuff, so he had quite an important position there.

Senesino, by comparison, sang for thirty-three or thirty-five years – we used to think he made his debut in 1707, but recent research suggests he may have started even earlier…

The album includes repertoire spanning virtually his entire career - do you see the later composers working around the increasing technical limitations of an ageing voice?

Yes – it’s so interesting to look at the whole canon of his work and see these little differences. When he was just starting out his voice was essentially a high mezzo, and he wasn’t delving too much into the lower range, other than for occasional dramatic effect. Then in the middle period of his career, as we see in the Bononcini arias, it seemed like he could do everything: highs, lows, coloratura, triplets, the whole lot.

After he returned to Italy from London in the later 1730s you see certain composers trying to support the voice more, for example by doubling his line in the violins. Sometimes that’s just a stylistic feature (Vivaldi for instance wrote a lot of unison arias with violin because it was simply his style), but towards the very end of his career it does seem like it was a useful tool for giving him a bit of reinforcement.

His lower register seems to have remained quite strong until the end. For example, in Giaj’s ‘Fra l’orror’ there are a lot of low As against a big orchestration, including a pair of horns, which suggests that part of Senesino’s voice was still something composers knew they could use as a showpoint.

Giaj was a completely new name to me, and there's so little information about him in the public domain: tell me a little more about him…

Giaj was the big surprise for me too: in his career, he wrote eighteen large-scale vocal works, including operas, which isn’t a small number! He spent most of his career in Turin, which had a very wealthy court: there was a lot of money there to produce opera, so he was bringing in major singers like Farinelli, Faustina and Senesino, and everything was quite lavish. He didn’t travel a great deal, but his works were also presented in Venice, so he’s someone who was really known in the eighteenth century: composers would come to Italy and seek out his music, and once they’d heard it on stage, they’d have copyists transcribe arias to take back with them.

His family had French roots, and the surname was originally ‘Jay’ - when they settled in Turin people didn’t know what to do with it, so it’s spelled about seven different ways in the sources and I had to just decide on one for the album! It’s fantastic music, and he’s just one example of these seven composers on the disc that I think we are in a place to understand more about, now that we know Handel so well.

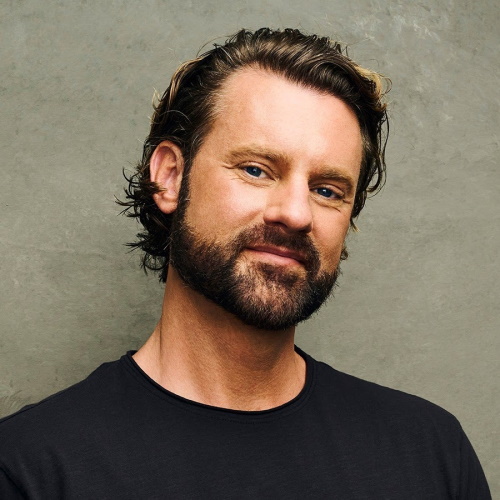

What’s the story behind the cover-image?

The fantastic jacket I’m wearing was made specifically for me, for a production of Giulio Cesare. They absolutely went to town on costumes, and there were ten different looks: two for me and amazing gowns for Cleopatra in every scene! That was one of the first Senesino roles I did, and as soon as I put that garment on, I felt I could immediately embody the strength of the character: sentimentally, I wanted to connect to that and represent it on the cover of the album, and the company kindly let me rent it for the photoshoot.

The photographer was actually a neighbour of mine! My partner’s a wonderful graphic designer, so he enhanced it afterwards and made it into the majestic image that you see on the cover. I think it really sums up how Senesino viewed himself – the heroic king who’s above everything, not just on stage but in his everyday life…

Randall Scotting (countertenor), Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, Laurence Cummings

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC