Interview,

Michael Waldron on Colourise

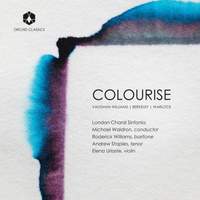

Featuring music by Warlock, Vaughan Williams and Berkeley, London Choral Sinfonia's Colourise on Orchid Classics was one of my personal favourites from this summer's crop of new albums - the chief attraction for many listeners will be the first-ever recording of Berkeley's ravishing Variations on a Hymn by Orlando Gibbons, though Roderick Williams's eloquent account of Vaughan Williams's Five Mystical Songs (given here in the composer's own arrangement for baritone, choir, piano and strings) is also worth the price of the recording in itself...

Featuring music by Warlock, Vaughan Williams and Berkeley, London Choral Sinfonia's Colourise on Orchid Classics was one of my personal favourites from this summer's crop of new albums - the chief attraction for many listeners will be the first-ever recording of Berkeley's ravishing Variations on a Hymn by Orlando Gibbons, though Roderick Williams's eloquent account of Vaughan Williams's Five Mystical Songs (given here in the composer's own arrangement for baritone, choir, piano and strings) is also worth the price of the recording in itself...

I spoke to conductor Michael Waldron last month about how the Berkeley piece came onto his radar after all but disappearing from the repertoire for nearly seventy years, why he thinks it's never achieved the popularity which it deserves, and how both the Five Mystical Songs and The Lark Ascending spring into sharper focus in their chamber-choral incarnations...

How did you originally come across the Berkeley piece?

The discovery was really pure fluke. I was just browsing through the choral scores in Chappells/Yamaha on Bond St one day, and pulled out this score for choir, string orchestra, tenor soloist and organ: that’s exactly the kind of remit of the London Choral Sinfonia, and at four quid I thought I’d take it!

Then it lived in the pile of music on my piano for a while, but once I played through it I realised it really had legs and would sit nicely on the recording I was planning, so I wrote to the publishers asking if they knew of any existing recordings. They could only find evidence of one performance by some random provincial German choir in the early 1990s, and certainly no recordings, so I then got onto the Lennox Berkeley Society who were immediately very enthusiastic. They said: ‘We think this is a great piece, and Britten was involved in the premiere and thought so too - we’ve got no idea why it’s never been recorded!’.

What are your own theories on why it vanished from the repertoire?

I think there are two possible factors. The first is that Britten is such a dominant force in mid-to late twentieth-century music that sometimes people don’t go out of their way to profile his contemporaries, apart from a relatively small number of celebrated works.

Perhaps it’s also suffered from its duration and instrumentation: at just under 19 minutes it’s a slightly awkward length, and from a logistical and financial point of view it’s a bit on the short side for the effort required. You need to assemble an excellent tenor soloist, a great choir, very good string-players and a venue with an organ, and once you’ve pulled all those forces together you’ve only got one half of one half of a programme, so what do you put alongside it?

But people who are skilled at putting concert-programmes and budgets together could still make it work - do something else with a tenor soloist in the other half, do something that’s strings-only, do something with strings and choir…there’s no reason for it not to be in the repertoire.

What do we know about its reception at the premiere?

It was premiered at the Aldeburgh Festival in 1952, and by all accounts it wasn’t a great performance: it was under-rehearsed and didn’t go as well as it might’ve done, so maybe that’s been a factor in why it’s not endured. But Britten wrote to Berkeley afterwards and was very complimentary about the piece itself, so it did get a positive reception in that sense. Peter Pears sang the tenor solo, and it’s very much written with him in mind.

Before we even started rehearsing, our soloist Andy Staples said to me that the tenor writing is almost Britten-esque, because Berkeley knew the voice he was writing for and played to Pears’s strengths. Rather than going in for the sort of declamatory octave leaps we see in a lot of dramatic tenor writing, he takes a much subtler approach: it sits in that very tenorial, clean high register around F/G, where Pears’s voice was at its strongest, so it’s very powerfully written in that respect.

How close were Britten and Berkeley at this point in their careers, and how much do we see their personal relationship reflected in the piece?

I knew there had been some sort of romantic association between Berkeley and Britten, but I didn’t know the full extent of it until the opera critic George Hall (a very good man, and the font of all knowledge!) got involved with the project – George views the piece as a love-letter, and I feel very much the same now.

We know that Britten and Berkeley had some sort of relationship quite early in life, but when Pears arrived on the scene and he and Britten went over to the States there was a parting of the waves in all senses. When they returned to the UK there was a rapprochement of sorts – by this point Berkeley was married anyway, and the two of them re-established their connection, albeit not in an active physical sense.

After talking to George in detail about all of this, I really saw the piece in a different light. It’s based on a hymn-tune and they are verses of a hymn set to music, but there’s something almost sensual about the writing - the third verse, which is just for tenor solo, is like a love-story set to music. There’s not much God in there, let’s put it that way!

And we see a similar blurring of boundaries between sacred and secular in Vaughan Williams’s Five Mystical Songs…

Yes - there’s a spirituality to those texts which isn’t necessarily just religious, and that’s what I love about these pieces. He uses the O sacrum convivium plainsong for the (wordless) choir at the end of one of the songs, but so much of the rest of it is just beautiful English song: there are choral interjections, sure, but it’s mainly a showcase for the baritone, and there’s something so human and direct in the way he sets those words.

And Roddy’s performance here is something else: the range of colours in the voice and the way he looks after every word without it ever feeling mannered or affected is just next-level stuff. It’s a masterclass for anybody in English song.

What’s the story behind the version we hear on the recording?

I’d love to be able to say I’m a great detective, but again that was down to pure luck! LCS had previously done the Serenade to Music in a version with identical scoring – the vocal parts were the same and the orchestral accompaniment was strings and piano. It says quite clearly at the top of the manuscript that the arrangement was by somebody else, but apparently it was sanctioned by Vaughan Williams. In the lead-up to his 150th anniversary I started thinking that we should do the Five Mystical Songs, and went on the Oxford University Press website to look at the full orchestration and see which instruments were absolutely necessary. The short description said ‘or version for organ and piano, or version for strings and piano’, so I just assumed it was another one arranged by somebody else - probably the same guy that did the Serenade to Music…

We did it in concert and I thought it worked very well - in fact better than the Serenade to Music, in terms of the textures and colours - so I wrote to OUP asking who’d arranged it, and they replied that it was actually Vaughan Williams himself! We couldn’t find any evidence of it being recorded, so it seemed like an obvious choice for this disc.

Paul Drayton’s arrangement of The Lark Ascending was also a new discovery for me – how did you find it, and how much does it differ from the original?

That was something else I came across when I was researching our plans for RVW150: orchestral and choral excellence is at the heart of everything we do, so it fitted our remit so well. The Lark is Classic FM’s No. 1 piece every year, so I knew that people liked the piece, but I thought a few die-hard followers and music critics might be a bit sniffy about the arrangement…when we did it in concert, though, everybody was so positive about it. A pretty decent recording exists already, but I felt LCS had something more to say about it; we had Adrian Peacock as our producer and Dave Hyatt as our sound engineer, and I swear those guys do black magic when they record things!

Elena of course plays it absolutely sensationally: we were introduced through Orchid, our mutual record-label, and it was a dream to have her on board. One of the things which she and I discussed was how effective this choral arrangements is in the quiet moments, where the violin writing is super-delicate: there’s just a much smaller sound-world from the backing, which allows some of the really minute detail to register more clearly than it does on recordings of the full orchestral version where the mics have to capture a much bigger sound-world.

Most of the writing for choir is just a translation of the orchestral parts, but of course voices bring a different sort of timbre and clarity, and I think it sheds a very new light - more of a focused laser as opposed to the big floodlights of the symphonic version. And hopefully that’s one of the attractions of this album: alongside the world premiere of the Berkeley, we have a different take on one of the best-loved works in the repertoire, and I wanted to highlight the fact that contemporary arrangers can offer a valid new perspective on existing popular works.

Andrew Staples (tenor), Roderick Williams (baritone), Elena Urioste (violin), London Choral Sinfonia, Michael Waldron

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC, Hi-Res+ FLAC