Interview,

Harry Bicket on Handel's La Resurrezione

Musical responses to, and settings of, the Passion narrative that sits at the heart of Christianity are not hard to find. A huge number of composers over the centuries have found inspiration in the dramatic events leading up to the Crucifixion. But at that point the story tends to end; the listener is assumed to know what happens next. Oratorios dealing with the post-Resurrection events do exist, but are relatively rare; James MacMillan's 2012 Since it was the Day of Preparation... is one such work that takes up the next part of the story.

Musical responses to, and settings of, the Passion narrative that sits at the heart of Christianity are not hard to find. A huge number of composers over the centuries have found inspiration in the dramatic events leading up to the Crucifixion. But at that point the story tends to end; the listener is assumed to know what happens next. Oratorios dealing with the post-Resurrection events do exist, but are relatively rare; James MacMillan's 2012 Since it was the Day of Preparation... is one such work that takes up the next part of the story.

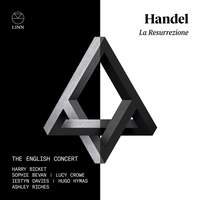

Another is Handel's much earlier La Resurrezione, a lavish and colourful work commissioned by a wealthy patron while Handel was working in Rome in the 1700s. Conductor Harry Bicket's new all-star recording of La Resurrezione with The English Concert certainly gives this flamboyant work the treatment it deserves; I spoke to Harry about where La Resurrezione came from and what makes it so different from many of Handel's other sacred works.

This piece is so lavish, and it seems to be what today I guess we’d call a flex by the patron, Ruspoli. Were we ever in danger of it falling into an archive and never being rediscovered?

I think it’s always been around… but Handel, like every composer, went out of fashion because everything in the eighteenth century (and into the nineteenth century) was all about new music, so people weren’t doing pieces that were old. The original Academy of Ancient Music was set up to perform music that was more than twenty-five years old: that was the definition of ‘ancient’ music! So it wasn’t surprising that people said ‘Yes, of course there are all these pieces’.

Bach was dropped for years and years until Mendelssohn started saying ‘You should listen to this guy’ and started doing organ recitals and the St Matthew Passion - now we can’t believe that, because where we would be in our concert-programming without Bach? So this piece was always there, but I think also as you say it’s very lavish… That’s fair enough if you’ve got a wealthy patron who wants a lavish show with lots of effects - that’s why he’s paying for it! - but obviously if you’re going to take a financial risk yourself you don’t do an expensive show. And as Handel got older and moved to London he started being his own impresario and selling tickets for his own concerts and taking the financial risk himself. I don’t think he ever wrote anything quite like this again.

One of the great things about this piece is it’s at the roots of everything that Handel ever wrote. Handel was well known for recycling a lot of his stuff – and a lot of other people’s stuff – all his life, and there’s barely a number in this piece where you don’t go ‘Wait a moment, that sounds familiar… Oh yes, he uses that in Agrippina, or he uses that in Rinaldo, or many years later he rewrote it for this other thing’. So it’s a fascinating piece in that respect, but having said that there’s also some totally original music there which he never re-used, and is so virtuosic and so completely off the charts in terms of wildness.

One of the things I love about early Handel is that it’s really wild – as he got older he kind of refined his art in a way so that he used fewer notes. It wasn’t that he got more staid in his writing, it just became more distilled. But he wrote this piece as a young man who hadn’t had his big hit yet – he was a pretty unknown composer so he had nothing to lose and everything to prove. There’s a kind of abandon about the way he writes here – I love early Handel because it’s so wacky and crazy, but also very heart-on-sleeve.

So he doesn’t really have a hard and fast boundary in his head between the sacred and the secular music here?

No, it’s funny – the little C major aria ‘Ho un non so che nel cor’ in this piece becomes another aria in Agrippina, which is about as secular as you can get – it’s the bawdiest, real playing-to-the-peanut-gallery kind of piece you can imagine. I was doing Agrippina two years ago at the Met, just before the lockdown, and Joyce DiDonato who was singing Agrippina came up and said ‘I never understand – why is this aria even here?’ And David McVicar who was directing said ‘Oh, well it originally comes from La Resurrezione’. At that point I hadn’t really done La Resurrezione, and when we started working on it I looked at it and thought ‘What is this aria doing here?!’ It’s a very weird piece. When we were recording it I said this to the orchestra – we have a lot of very brilliant, clever minds in the orchestra, and our second violinist who always knows the source of every piece of music we play and has all the original manuscripts said ‘Oh well it’s only in La Resurrezione because it’s actually a violin sonata by Corelli!’ Corelli was the principal violin at the premiere of La Resurrezione – he led the orchestra. So the reason why it’s there is that as a tribute to his leader Handel took a violin sonata of Corelli’s and set some words to it – it wasn’t even really because it necessarily reflected the text (although it reflects it better in La Resurrezione than it does in Agrippina).

There are often other reasons why these repurposings happen. ‘Lascia ch’io pianga’, one of the most famous arias Handel ever wrote, started off just as a sarabande movement of an Overture to an early piece which Handel wrote when he was in Hamburg. Then he puts words to it in Rinaldo, and now you hear it in every elevator in the world and what seems like every TV advert - everyone goes ‘Oh brilliant!’, but that’s not why he wrote it.

So in the original performance context – would it have been a very small audience like a private screening, or a larger gathering for Ruspoli to show off to a bigger audience?

It was a private, exclusive thing. I think the room where it was premiered is still there – I haven’t been there, but I don’t think it was huge and the orchestra probably took up a lot of it. As you say it was a huge orchestra and a smallish cast, but it was all about the effect and the instruments. We know from writing that he used a trombone; we don’t know where because there’s no trombone part, but we know it was in there somewhere because we have the receipts of what he paid the musicians.

The trombone had gone a bit out of favour at this point; it never completely died out, but it hadn’t really come back into the orchestra… So why was he using it, and how was he using it?

He uses it to solidify the bass – he essentially uses it as a continuo instrument, and that’s probably why there isn’t a part, because the trombonist would’ve just read off a bass line. And when we’ve done it in the past I said to the trombonist ‘Look, you’re just going to have to make up your own part’. The writing isn’t really trombone writing – you play what we call a structural bass. You don’t play literally every note of bass line – you play a tonic note, a dominant note and maybe a little arpeggio or something if that works on the instrument. You don’t really hear it – it’s not like it’s a big voice – but it adds to the sonority.

On the vocal side of it, Handel got into a bit of trouble – he used a castrato for the Angel, but it was Mary Magdalene who really caused problems, because he used a female soprano and then had a sudden warning from the Pope ordering him not to! In the light of all that, did you consider using a male soprano on your recording?

No, because I don’t know any male singers who could possibly do that: Handel of course had castrati, and basically countertenors just don’t sing up there. I’ve done the piece with a female Cleophas – here Iestyn Davies sings Mary Cleophas, so it’s slightly strange in that he’s playing a woman. In Handel because it’s usually the women that play the men, not the men that play the women! But in the historical context of this, I think that was fine. Also you have to remember that in the eighteenth century people didn’t worry so much about the sex of the character, but they did worry about the pitch. We know that when Handel rewrote stuff for a different voice he didn’t just say ‘Sing it down an octave’ - that never works, because you’d get all sorts of inversions of harmony and things like that.

This recording was done in lockdown; the previous year we’d already lost a big tour of Rodelinda, though we did manage to record it. For Rodelinda everybody was six feet apart, and it was actually a really, really hard couple of weeks’ work – I think it came out well, but it was really not the way we normally play. We were due to do Tamerlano this last year, and then for all sorts of reasons it fell through: COVID came back, a lot of our venues had lockdown, then the guy singing Bajazet got COVID a week before we were due to start recording…We realised we were never going to get somebody to sing the role such short notice, but we’d done La Resurrezione in the gap between lockdowns with a slightly different cast and as we had all these singers booked for Tamerlano I said ‘Why don’t we just try and record La Resurrezione with as many of these singers as we can? They’re on contracts and we know they’re free, and we promised them the work…’. Iestyn was one of the people who’d been booked to sing Tamerlano, so I thought it made perfect sense for him to sing Cleophas. And I also think that was a very Handelian solution – it’s exactly the sort of thing that Handel would do. He was a very pragmatic musician, and if somebody wasn’t available he’d say ‘Well OK, we’ll use you, and we’ll tweak this’. So that’s how the casting happened.

She seems to have been quite a character, this ex-Queen of Poland who employed the librettist, Carlo Capece - did she have any input into the libretto other than just keeping him fed and housed?

I don’t know, really, but I’m always very interested that this libretto has very striking similarities with a piece by Stradella - a Christmas cantata which has a similar theme in that the whole thing starts with Lucifer kind of cursing because he hears that Jesus was born, and it’s sort of almost humorous in a way!

It’s like those bits of Paradise Lost…

Exactly, which of course were hugely influential on this whole world. And we know that Handel knew Stradella, because used a lot of Stradella’s music in Israel in Egypt, so I wonder if he also thought that that was a model which he could also use for the Resurrection story. But beyond that, the libretto itself is a funny mix – I think as Handel got older, he got more proactive in terms of guiding his librettists to what he felt would be the most theatrical solution. I don’t know if you’ve ever been in a situation where you work with a librettist or whatever – in my other hat at Santa Fe Opera, we have a new commission every year, and it’s fascinating to me how now the librettist writes the libretto and then the composer writes the music. Back in the eighteenth century there was no way that would have happened, and it was a very collaborative or very combative process: Mozart and Da Ponte, for instances, was not a relationship without its fights about what they felt would be most theatrical. But I think that at this point in his career Handel was maybe less assertive: there’s quite a lot in this libretto (particularly in the recitative, and at least two arias) which I feel are a bit overwritten and overblown. He was probably just thrilled that he’d got this commission and thought ‘OK, these are the words I’ve got to set – I’ll just crack on with it!’.

Mary Magdalene, Mary Cleophas and St John aren’t that surprising characters to see in a work like this - but it is quite surprising to see the literal Devil! Given all the restrictions about women and all of that, did they not get any flak for putting the Devil on stage?

It’s a really good point. Of course I’m not such a Bible expert, but I’m not sure there’s much writing there where the Devil is personified in this way, other than the Temptation in the Wilderness. The music that Handel writes for the Devil is very theatrical and could easily be played in a very camp way. It’s like that movie where Robert De Niro plays him as a guy called Louis Cyphre! Of course Lucifer’s a bass, and of course his part’s very wide-ranging, because that’s how those characters were musically described. I’ve done performances where basses snigger and laugh and do it in a very pantomime kind of way, because the music can feel like that as well – but I think we just chose not to do that too much because I don’t know quite what sort of piece it becomes then, especially on disc where you don’t have the visual element for context.

There is some Handel which is very vaudeville in the best sense – the whole Venetian carnival tradition which he would have known, has this thing. You see it in something like Monteverdi’s L’incoronazione di Poppea, where you have Arnalta (who’s a man in drag) singing about how she’s not going to get all her perks any more with the change in regime, and it’s very funny and witty, but then it’s immediately followed by Ottavia being banished from Rome in this incredibly long lament ‘Addio Roma’. So there is that kind of carnival thing where Handel and many composers juxtaposed very comic scenes with very serious scenes. As you said earlier, ‘What is this piece? IS it a sacred piece, or is it a secular piece?’. It’s based on the scriptures, but it wasn’t performed as part of a religious ceremony: for instance, it’s not like doing the St Matthew Passion which was written for divine worship, it was an entertainment.

Another thing which struck me as a little bit odd is that not much actually happens in terms of a plot advancing – it’s more about the reaction of other people to the main event which is never seen, and of course there isn’t a Christus coming and bopping the Devil on the nose…

And no Evangelist, either. That’s Handel though, isn’t it? You see that also through the operas, where the action is forwarded by the recitative: the arias are never about pushing the action forward, they’re about the characters’ emotional responses. I’ve just come back two days ago from doing the St Matthew Passion with the BBC National Orchestra of Wales, where I was asked the same question about the candour and it was the same thing – you have the Evangelist telling the story and other characters popping up. It’s quite linear, and the choruses do push the action forward, particular as the crowd: but the arias are absolutely about the human aspect and the human reactions. Of course in the St Matthew Passion a lot of them aren’t even given names, they’re just SATB; in La Resurrezione they are given names, and we know who all the Marys were. Then there’s all the references to what it means to be a mother and to lose your son, and that interesting little aria that the Angel sings about women. It’s quite a feminist piece, and the women are the main protagonists – John the Baptist makes an appearance and of course he’s this wild visionary, but it’s really the women that dominate this piece.

Was that unusual in itself compared to other things that were happening at the time? Was that Stradella cantata you mentioned similarly women-focused?

Yes, a little bit, and I think that ultimately comes from Greek tragedy – I think I’m going to be proved wrong on this, but if you look at Euripides the majority of the titles of his plays are women’s names. Women weren’t allowed to vote, and they didn’t have a place in society – but one place women were allowed was in the Odeon, in the theatre and I think that’s why a lot of the plays were written with women in mind. And in Shakespeare you have the whole thing about women on the stage too.

Lucy Crowe (Angel), Sophie Bevan (Mary Magdalene), Iestyn Davies (Mary Cleophas), Hugo Hymas (John the Evangelist), Ashley Riches (Lucifer), The English Concert, Harry Bicket

Available Formats: 2 CDs, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC