Interview,

Nicolas Hodges on Birtwistle and Beethoven

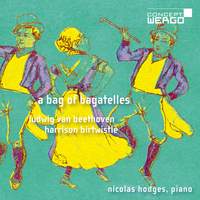

German-based pianist Nicolas Hodges – known for his interpretations of contemporary music, and a regular dedicatee of new works by living composers – talks about his recent album Bag of Bagatelles. The recording sees Hodges juxtapose works by Birtwistle, with whom he has a long-standing and close musical relationship, and Beethoven at perhaps his most improvisatory. The two composers might seem on the surface to share little in common, but as Hodges explains, there's more linking them together than one might expect.

German-based pianist Nicolas Hodges – known for his interpretations of contemporary music, and a regular dedicatee of new works by living composers – talks about his recent album Bag of Bagatelles. The recording sees Hodges juxtapose works by Birtwistle, with whom he has a long-standing and close musical relationship, and Beethoven at perhaps his most improvisatory. The two composers might seem on the surface to share little in common, but as Hodges explains, there's more linking them together than one might expect.

Birtwistle comments that he often doesn’t know how one of his compositions will turn out, likening it to growing a plant from its seed. But once the composition has been written and pinned down on the page, that unexpectedness can be lost – how do you recapture that feeling in performance?

I do this both in performance and in my life, in different ways. In performance, you are in a sense at the mercy of the composer; they have to articulate whatever came out of the chard seed in a precise way on the page, and then you interpret that as precisely as you can, as a musician. But there’s another aspect to it which feeds into it, which is what I meant by “in my life” – every time I play a piece again, I’m always surprised by it, even if I’ve known it from memory for twenty years. I remember an earlier piece of Birtwistle, Harrison’s Clocks - when I played that again after many years, I thought that I was actually playing parts of it wrong! So I went rushing back to the score to check, and it turned out that I was playing it right after all – but the passage of time leads you to hear things differently. It’s often compared to walking around a sculpture – that’s a common analogy when talking about modern music, but I think it really is true. It’s the same object but you see it differently because of walking round it or the passage of time.

Changes in who you are as a person also matter – I’ve changed a lot over the years. I’m fifty now, and while I don’t feel old, I do feel that some water has gone under the bridge and I’m not a youngster any more, and there are periods of my life when certain things were present and other things weren’t; my relationship with particular composers has changed over the years, as has my relationship with pieces. And I absolutely love that – the honour that I have of being able to play really great contemporary music more than once! Playing a piece of Birtwistle once is great, but to get to do so on tour and to do strong pieces multiple times is really fantastic. There are pieces that I’ve played forty or fifty times, and that brings not just slickness but a lot of context and peripheral considerations, and different views on the material.

People do come to my concerts and hear the same pieces, because of the way that I cycle through the repertoire during the year, and they comment backstage on how different it was to the previous time they heard it. People aren’t really aware of the interpretative role of the performer in contemporary music – nothing like as much as they are in Classical and earlier music. When someone goes to a concert and hears, for example, Maurizio Pollini playing Stockhausen, which he does occasionally, they’re hearing someone who’s known that music for fifty years and deeply loves playing it – but his public will probably never have heard that piece before, and it’ll just sound like complete gobbledygook to them, whereas in reality they’re hearing someone who has thought very deeply about it, and who has a lot of experience of it and of playing it in different ways.

Beethoven’s baffling Fantasy Op.77 shows clear influences from his experiences as an improvisatory pianist – more so even than the Bagatelles. How far do you think it’s possible to trace the impact of improvisation in Beethoven’s output generally?

I’d actually challenge the assumption there. On the one hand it’s obviously true that it’s an improvisatory piece – I even read recently that we know, or at least strongly suspect, which concert Beethoven first played it at as an improvisation. But there’s a very crucial difference which is that it’s now a published work, printed and fixed with an opus number. That means it can’t be an improvisation any more. There was probably an original improvisation, and he made some notes on what he did and then composed a piece using those ideas. But at some point he’s definitely sat down and composed. It’s not simply a transcription from memory.

Having said that, if you look at it the other way round, a composer like Beethoven who we know wrote very quickly – you can see it from his manuscripts – probably everything he wrote was improvised, in a sense. The music came out of him pretty quickly a lot of the time, I think. I’d contrast him with Mozart, who was producing huge amounts of stuff all of his life, but that was largely because he was operating in one very small area within the possible musical and stylistic languages, so to speak, staying in that one place. And in that position it’s easier to produce more stuff.

The Birtwistle Variations from the Golden Mountain seem to have taken their final shape only in the recording session itself, in a collaborative process between Birtwistle and yourself that “discovered” a way to end the piece. Is that level of exchange between performer and composer common, in your experience?

No, that’s not normal at all. In a way it’s a function of my own relationship with Birtwistle. Most composers write down what they think they want, and then you go from there. There are some composers who don’t know what they want, and in rehearsal they’ll say “what do you you think?” – and that always really upsets me because when a composer asks my opinion about what I should be playing in a particular piece, that makes the composer look rather weak in a way.

But with Birtwistle in this example, he knew exactly what he wanted, he just couldn’t put it into words and couldn’t find it and notate it as a concrete musical thing. It’s actually a long story – in the score it says you can do one thing, or you can do another, and I called him and asked him what he really wanted, and he said he wanted a sound that was really hard, and high, and not a normal sound, but had to be played on the piano. So I told him what I was going to do and he said “OK, do that”. And at the premiere he came up to me and the first thing he said was “It wasn’t right”! And at every concert where I’ve done this piece and he’s been there he’d always say the same thing. I’d use different preparations, or a wood block as a separate instrument where I’d have to take up a stick and play it. Every time he’d say “No, it’s got to be more like this” or “it’s got to be more like that”.

In Cologne what I think triggered it was that we had instruments all over the stage, because we were recording during an orchestral week. In the evenings the orchestra was in, so the whole percussion department was out on the stage, including a celeste. And Harry just started walking around hitting things! And he’d still be saying “no, that’s not right, that’s not right” – and then we started messing around with the celeste and I played something, and that was very close, but the sound was too quiet. So I played it on the piano – and it ended up just being a cluster of chromatic notes high up on the piano. But I’m sure that in a way the process of searching for it was important to him – to find the right sound, not just an approximation.

In addition to the Fantasy, you include Beethoven’s six Bagatelles Op.126 on this album as a counterpoint to, and reflection of, Birtwistle’s piano works. What do you think are the main qualities that Birtwistle’s writing shares with Beethoven’s?

To be honest, I just put them on the CD because I wanted to record them! But these pieces are, first of all, very enigmatic. Each individual one is quite straightforward, and does what it says on the tin. But as soon as you put two or three of them together, you start to think, “What is this? Is it one piece? A cycle?” To me, it’s obviously one piece and yet they’re all different and somehow not related. It’s amazing how it hangs together. It reminded me of something I read about the Debussy Préludes, which is that it’s very hard to say why they’re in that order, but if you try to play them in a different order from what Debussy chose, it doesn’t work. It’s the same with the Beethoven. You can mess around with the order of them, but if you do that, you realise that it just doesn’t work except in the intended order.

I find that aspect very mysterious, and it’s the same with Harry’s music as well. He can put very simple things together in a way that makes you say “Oh my God, what just happened?” Obviously there are many other aspects, too; Harry is a very contrapuntal composer, in a way that’s quite close to Beethoven in a sense. With both of them, I think of orchestration when I’m studying their piano music. Harry has written so much big orchestral music, and the operas as well – a huge number of hours – and you can feel that with the piano music, much more than with, say, a piece for solo oboe. The orchestra is somehow kind of in the background of his imagination when he’s writing for the piano.

The second substantial Birtwistle work on this album, Gigue Machine, was dedicated to you personally – can you tell us a little about your own relationship with Birtwistle?

It’s evolved over time. When I was in my ‘20s we were with the same agent, Andrew Rosner. And I had assumed that one of the perks I would get from that would be instant access to Harrison Birtwistle! Which obviously turned out not to be the case – that’s just not the way the world works and it’s not the way people work. Harry and I had to find each other in our own personal way. I said in an interview during the recording that we’re “kindred spirits”, and I said it in a rather tongue-in-cheek way, but he took it very seriously and said he really did think that was the case, that we have some traits in common.

In relation to Gigue Machine, you observe that “the ‘machine’ always falls apart, fails somehow” – yet you clearly don’t consider this disintegration a failure on the part of its ‘creator’. As a performer, how do you square the circle between pieces that are supposed to come apart at the seams, and deep-seated musical expectations of coherence and satisfying structures?

I think I’d go back to what I was saying earlier – if the composer has done their job, and I play what’s on the page, it will work. And I do mean that quite literally, in the sense that you shouldn’t have to make the piece sound like it’s “not working”; it should just happen. I’m reminded of the recapitulation of the Eroica’s third movement, where the horn entry comes in early – I don’t think anyone, except perhaps at the very first performance, has ever thought that was anything other than Beethoven making a joke. No-one really thinks it’s “wrong”, and I think that’s to do with the way it’s contextualised and put in its place.

It’s a question of the integrity of the whole work of art; this is music that’s composed and created in a very high-level way, and it’s not going to suddenly sound like it’s somehow incompetent just because it’s in danger of falling over. There are lots of places where it feels like it’s fallen apart or run out of energy, but so much of it is so dynamic and motoric that those moments where it fails only ever sound deliberate – part of the whole object.

Nicolas Hodges (piano)

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC