Interview,

Antonio Pappano on Donizetti's Queens

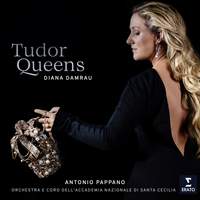

The German soprano Diana Damrau has sung Donizetti’s Maria Stuarda at several major opera-houses over the past couple of years, but her partner on her new recording focusing on the composer’s three Tudor queens is a rather more recent convert to this repertoire – barring a youthful stint as a repetiteur for Anna Bolena, Sir Antonio Pappano had never worked on these operas until they embarked on this project in Rome last summer.

The German soprano Diana Damrau has sung Donizetti’s Maria Stuarda at several major opera-houses over the past couple of years, but her partner on her new recording focusing on the composer’s three Tudor queens is a rather more recent convert to this repertoire – barring a youthful stint as a repetiteur for Anna Bolena, Sir Antonio Pappano had never worked on these operas until they embarked on this project in Rome last summer.

I spoke to him last month about the differing demands of the three works, the special qualities which Damrau brings to this music, the challenges involved in putting these operas on stage, and why the Tudor queens continue to be such a rich source of inspiration for novelists and film-makers today…

How common is it for a single soprano to tackle all three Tudor Queens?

All three operas are extremely demanding, and for very different reasons: Roberto Devereux is the most declamatory of them, and Anna Bolena’s incredible outbursts require the greatest control of line, so I think the numbers of sopranos who will try to tackle this trilogy will always be very small. But what’s interesting (and I think this has always been the case) is that this repertoire has attracted more dramatic voices as well as the lighter lyrical ones - we tend to think of the bel canto repertoire as a lighter genre, but the dramatic content of these pieces appeals to the bigger-voiced girls too if they have the technique to manage all the demands that are put in their path.

By the time we get to Roberto Devereux, operas like Nabucco and Macbeth are not that far around the corner – do we know how familiar Verdi was with those works, and might he have drawn on them when it came to creating characters like Abigaille and Lady Macbeth?

He certainly knew most of Donizetti’s output: Verdi definitely came from a particular school, and that school is the Donizetti-Rossini line. Donizetti was of course dealing with an established bel canto template, but in these works he somehow outdoes himself - he’s constantly pushing its limits, and Verdi obviously sensed that. Especially with Roberto Devereux, I think his response was: ‘Wait a minute: if the style can encompass the line of the bel canto but become more declamatory at the same time, then I can create characters that are truly larger than life’. And I think he was acutely aware of not only Donizetti but also Rossini: when you look at the late Rossini operas like Semiramide (I say ‘late’ - he was only in his thirties when he retired!), they’re full of moments where you think ‘Verdi really could have written this’.

In terms of Donizetti’s approach to orchestration, how much progression do we see from Anna Bolena in 1830 to Roberto Devereux in 1837?

Donizetti’s orchestra is basically a Beethoven orchestra plus trombones (Beethoven does use trombones in symphonies Nos. 5, 6 and 9, but I wouldn’t say they were part of his basic working model). The challenge this presents today is that Donizetti’s use of the brass is often not especially refined: the instruments were smaller back then, and if you’re not using original instruments then as a conductor you’re constantly having to do what I call ‘surgery’ to balance the brass with the strings and the woodwinds. This is something Verdi certainly went on to develop in interesting directions: if you look at a score like Nabucco you see that the brass is used more individually, whereas with Donizetti it tends to be deployed in all the familiar places! (That said, Donizetti’s writing for woodwinds in Maria Stuarda and Anna Bolena is often extremely beautiful, and he makes some wonderful use of the horns). I think that despite being the latest of the three operas Roberto Devereux is somehow more simply written than the other two. Its effect is more direct - it achieves drama through a more declamatory vocal style and the more judicious use of a bigger orchestra, and that’s a progression which Verdi would really think about…

One very specific question about this recording: how did you achieve that arresting cannon effect in the final scene of Maria Stuarda?

I’m glad you noticed – I was actually quite underwhelmed with the original effect when I heard the first edit, so I begged the engineers to use the sample of the cannon we had for Otello instead!

These three women continue to exert a strong fascination for us today, with the past few years bringing a slew of new adaptations of their stories on film and TV and in popular fiction such as Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall trilogy – have any of these contemporary depictions fed into your perspective on Donizetti's settings?

I think we undeniably retain a certain fascination with royalty in our society - look at where we live and at how much news is generated through their good works, through their foibles, through their political involvement or non-involvement… It’s all bound up with our relationship with tradition, and that's something that doesn’t jibe at all with our lives today but which we somehow still need as a point of reference. Diana and I really approached this project dramaturgically together, and when you try to put yourself in these situations involving matters of life and death, betrayal, destruction of countries and borders, you see that the burden was (and is) huge. I think that we can learn from people’s responses to that at any time, and it’s no wonder that Donizetti was particularly inspired by the material.

So my sense of discovery has not come from outside sources, but rather from the material itself, which I find extremely compelling. Doing this recording was a revelation for me, first of all because I’d never conducted any of these operas. I was familiar with Anna Bolena because I’d been a pianist for it many moons ago (I think in 1985) in Chicago with Joan Sutherland in the title-role, and I couldn’t believe the enormity of it: when you perform it without cuts it’s as long as Parsifal! For the conductor the bel canto repertoire is supposed to be, shall we say not exactly a must-do, but having just recorded Otello the week before this project I was so stimulated by the simplicity, directness and perhaps even lack of sophistication of this music. It really won me over, and I’m definitely a fan now: this stuff is absolutely incomparable.

Was this your first recording project with Diana Damrau?

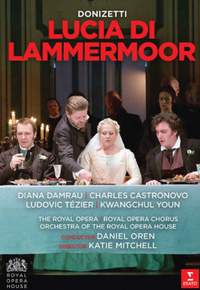

It was. We'd done some filming for the BBC a few years ago when I was making a documentary on Italian opera and she very kindly agreed to do some excerpts from Lucia di Lammermoor, which she sang quite wonderfully. Just recently we had a plan to do a bunch of recitals together in Amsterdam, Vienna, Paris and New York, but three of those were cancelled – New York because of the virus, and the other two because Diana wasn’t well. We did do the Amsterdam performance, though, which I’m very happy about, because it was such a beautiful programme – all music by operatic composers, so Rossini, Bizet, Strauss. Hopefully we’ll be able to pick that up again at some point, because I admire her so very much. Here’s a German singer who has made the Italian repertoire her own in a very sincere and probing way: Diana doesn’t give you just the glitz on the surface, but the real heart of it. That was absolutely the case when she sang Lucia di Lammermoor for us at Covent Garden a few years ago, which was an incredibly courageous performance.

Maria Stuarda was last staged at Covent Garden in 2014 - are there any plans to programme the other two operas there in the relatively near future?

I’m really not sure – it’s so difficult to plan anything at the moment for the obvious reasons, but these pieces do present particular challenges even at the best of times. Of course it all depends on the girl, but there are other issues to consider as well: major conductors are not typically drawn to this repertoire, and neither are many directors, because there’s an implicit conservativism in terms of the visual element. I guess I have to do them, but let’s see…!

In one of your Saturday morning ‘House Music’ broadcasts earlier this year, you mentioned the connection between bel canto and Beethoven, and when I listened to your recent Beethoven recital with Ian Bostridge I was very struck by that kinship. How much Italianate influence do you find in Beethoven’s songs?

I see An die ferne Geliebte as a very German affair – the bel canto element is less in evidence there than it is in the Italian settings. The emphasis is really on narration, whereas in a song like Adelaide you have very obvious bel canto reminiscences: Italian opera was hugely in vogue at that time, and I think Beethoven had the power of those Italian voices in mind when he wrote it. (Beethoven was a great admirer of Rossini, but specifically of the comic Rossini, which I find very interesting – he actually told Rossini that he viewed him as a comic genius). What the bel canto sparked in Beethoven was maybe not so much an admiration of the music itself, but rather a fascination with the possibilities of the voice, with the ornamentation that was part-and-parcel of that singing style, and you can really hear that in his piano sonatas. He saw that these singers’ skills and mobility could be harnessed to adorn, embellish and beautify the simplest of material, and like Mozart he took these elements of variation and coloratura and incorporated them into his writing for the piano to create a similar sense of wonder.

Diana Damrau (soprano), Orchestra e Coro dell'Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, Antonio Pappano

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC, Hi-Res+ FLAC

Ian Bostridge (tenor), Antonio Pappano (piano), Vilde Frang (violin), Nicolas Altstaedt (cello)

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC

Diana Damrau (Lucia), Charles Castronovo (Edgardo), Ludovic Tézier (Enrico), Taylor Stayton (Arturo), Kwangchul Youn (Raimondo), Rachael Lloyd (Alisa), Peter Hoare (Normanno)

Orchestra and Chorus of the Royal Opera House, Daniel Oren, Katie Mitchell

Available Format: DVD Video

Diana Damrau (Lucia), Charles Castronovo (Edgardo), Ludovic Tézier (Enrico), Taylor Stayton (Arturo), Kwangchul Youn (Raimondo), Rachael Lloyd (Alisa), Peter Hoare (Normanno)

Orchestra and Chorus of the Royal Opera House, Daniel Oren, Katie Mitchell

Available Format: Blu-ray