Interview,

Sarah Willis on Mozart, Mambo and Cuba

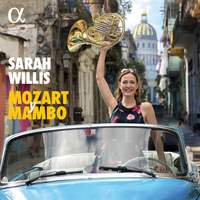

Widely-known for her work with the Berliner Philharmoniker and her extensive efforts to raise the profile of the French horn with a wider audience online, Sarah Willis has been exploring new musical paths in Cuba in an imaginative partnership with the Havana Lyceum Orchestra. Mozart y Mambo takes two seemingly wildly opposed musical idioms - the refined gentility of Mozart's Europe and the cosmopolitan vivacity of contemporary Cuban dance music - and finds a surprising amount of common ground between them.

Widely-known for her work with the Berliner Philharmoniker and her extensive efforts to raise the profile of the French horn with a wider audience online, Sarah Willis has been exploring new musical paths in Cuba in an imaginative partnership with the Havana Lyceum Orchestra. Mozart y Mambo takes two seemingly wildly opposed musical idioms - the refined gentility of Mozart's Europe and the cosmopolitan vivacity of contemporary Cuban dance music - and finds a surprising amount of common ground between them.

I spoke to Sarah about the music on this album, and the musicians she worked with in bringing it into being.

You refer to the comment made by one of your Cuban collaborators that “Mozart would have been a good Cuban”, and this providing some of the impetus for the creation of this. What do you think they were alluding to?

I asked them about this, and having spent quite a lot of time in Cuba myself now I totally agree! I was out and about the very first time I was in Havana, and I turned a corner and saw a quiet courtyard with a bust in it. And when I went a bit closer I thought it looked slightly familiar, though you wouldn’t really know it was him! But underneath it says “Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart”, and I thought “what’s he doing in Havana?” So I went back and spoke to members of the orchestra and they told me that the connection is mostly to do with the way their orchestra (the Havana Lyceum Orchestra) is supported by the Mozarteum in Salzburg, which is how it was originally founded. But when I asked them what they thought of Mozart, they told me everyone in Cuba knew him and that he would have made a good Cuban. And the answer turned out to be the way he uses dance-rhythms. In all his operas there’s always things to dance to – that light, airy, rhythmical style that he has. How many last movements of his symphonies make you just want to jig about? It’s completely there in his music.

It’s partly just the sheer joy of living but there’s also a darker side to him, and that’s very Cuban too; they have this incredible musical history of popular musicians who were, almost all of them, trained classically, which is something I didn’t know before I went there, but they do in many ways have quite difficult lives and there is a dark side to that. Sometimes there’s not enough food, the transport is a disaster and they never know whether they’re going to get to their rehearsal on time. Their day-to-day life is actually quite hard.

They all just seem to love Mozart, but I was very touched to see that they thought this way about him – because of his music, but also because he was good with the ladies! And of course for the Cubans that’s quite relatable.

But musically, I think it really is the rhythm and the dance, and the passion that also goes into it. So they definitely think he would have been a good Cuban.

You’re playing the more recently-uncovered version of the Concert Rondo K371, featuring 18 additional, previously unknown bars that you describe as making a huge difference to the demands the piece places on the performer. To the outsider, 18 bars doesn’t sound like a lot; what is it about this new material that’s so uniquely tiring?

Yes – these eighteen extra bars are killers. They’re early on in the piece – and the Concert Rondo is a very tiring piece at the best of times, because it stays in a certain range that’s quite tiring to play in. We like to have a rest now and then, even if it’s just half a bar, just to get some blood back into our lips! I’d never performed the Concert Rondo in public before, and when I said to Stefan Dohr, our principal at the Berlin Philharmonic (who is the strongest horn player I know) that I was going to play it on a recording, he said “don’t play it in the concert!” And when I asked him why, he said that it was a very tiring piece – and if Stefan says that, then it must be!

Initially I thought that looking at the notes it didn’t seem that bad; and then when you come to actually try and play it, the whole first page and a half (with these eighteen extra bars), it’s just a killer. It hovers around a certain pitch that really exhausts you. Personally I find leaps and intervals easier than staying in one range the whole time, and this is just relentless. The secret of it is to play it lightly – it was the first pre-release track of the album, and everyone was telling me how easy it sounded, and of course I knew just how much work it really was underneath.

The extra material, for those that are interested, comes early in the piece, just before letter B, where in other editions the rondo would come back in – but instead the lyrical material at letter A comes back in a sequential pattern. It doesn’t last that long but it certainly feels like it does.

What’s more, I actually ended up recording that piece at two o’clock in the morning – it was one of the last pieces we recorded. We had to record between 10.30pm and 2am because the church that we were using was right in one of the main streets in Havana, and Havana is pretty loud in the evening. This is also the piece where I incorporated a little bit of cheeky mambo into the cadenza – but I don’t think Mozart would have minded. I decided not to do this for the concerto, because it is a common audition piece – so if you put something out there, it is likely that some students will copy it. And I didn’t really want all the horn players in the world going into auditions and playing mambo there! So I thought I’d better stay classic for that, and put this little twist into the Concert Rondo instead.

The only complete concerto on the album is No.3 in E flat K447, widely seen as suited to lower players. That distinction between the low and high members of the section may be well established in Classical and Romantic horn parts, but is there still a perceptible gap between low and high players today, or is the modern horn player expected to be equally at home across the whole range?

Once you’ve got a job, if you are a second or a fourth horn you’re put into the box of being a low player and if you’re a first or a third you’re a high player. But, a good horn player has four octaves and while I’m officially a low horn player in the Berlin Philharmonic, but if you’re playing second horn in Shostakovich or Bruckner you have to play all the high stuff as well. There’s absolutely no way around having to practise your entire range every day. I tell all my students this – please don’t specialise until you really have to! When I got my job at Berlin it was a low horn job so I really did my best to beef up my lower range, but it wasn’t my intention to become a low horn player; I just wanted to be the best I could and get the best job I could.

I make it a point of pride to keep my high range up; I play in the Berlin Philharmonic Brass Ensemble where I’m actually the only horn player, which means hardly anyone will hear me because there are eleven brass players pointing outwards and I’m pointing backwards, and I have to really go into a kind of bodybuilding training for my lips before concerts like that! And likewise on this album – yes, I’m playing Mozart 3, which is maybe not the highest notes in the world, but in the cadenza there are quite a few top B flats, and also in the rest of the programme there are plenty of high notes here and there. It’s definitely a matter of pride as an official low horn player to get those in there!

The most apparent challenge in this project seems to be the melding of a fairly precisely-laid-out idiom with a much more improvisatory one, and you hint at having initially found this a challenge. How did you go about overcoming this, and do you think it’ll feed into your playing more generally now that you’ve done so?

To answer the second question first: Absolutely, there will be cross-pollination into my playing. I’ve found that my rhythm has got better since I’ve been working on this Cuban stuff, I’ve dared to improvise which is something I’d never done before. And also, I’ve just learned to love what I do more. I don’t know if you’ve seen any of the videos – the accompanying documentary came out recently – but you can see the joy that they have in making music with each other. As a professional, of course I’m always happy to be making music and I love my job, but there’s this pure joy that the Cubans have with everything they do – it’s very contagious. Those are all things I’ve definitely taken away.

I did feel like the stiff classical musician, and I still do, when I play with them – it’s got better, but I still feel that way. I did have one advantage, though, which is that I love salsa dancing, and the Cubans said I danced like a Cuban, which is one of the best compliments I’ve ever had in my life! I learned salsa dancing from a Cuban teacher with Cuban music, so I felt it in my body. And that’s the huge difference that you can see in these Cuban musicians: they have the music in their body. Whereas we classical musicians are sometimes encouraged not to move around too much while we’re playing, for them it’s almost involuntary, whether they’re playing Mozart or mambo, they put their bodies into it. Even when they’re counting rests! We count silently on our fingers, whereas with them you can see the shoulders moving.

It’s lovely to see; I did have that advantage of having the salsa beat in me, but I really had to learn. One other thing that was different was that coming from a German orchestra I’m used to playing behind the beat a lot, whereas the Cubans will play precisely on the beat, like an American or British orchestra, and I had to get used to that. It was very inspiring, and it went both ways; I was very strict with them about Mozart, phrasing, articulation, bowing, sound quality in both the wind and the strings, so I think we all really learned from each other.

You mention being surprised at the large number of horn players who attended a masterclass you gave in Cuba, and by extension at the vitality of its classical music scene. Why do you think we hear so little about this side of Cuba? Is it just at odds with most people’s pre-formed mental picture of Cuba?

I think many people don’t see beyond that. Classical music particularly struggles with that in Cuba, because about 95% of their economy comes from tourism and when people go there, they don’t think of going to a classical concert, they want to hear Cuban popular music. And of course I totally understand that, but it’s quite difficult. They do have an orchestra there, the National Symphony Orchestra of Cuba, and they have the Havana Lyceum Orchestra who I was working with, but it’s sometimes a struggle to fill the hall.

I was simply blown away by the standard of these musicians – and not just the horn players who I met on the first day there. They took me to their rehearsal and I met the conductor and listened to them play. There was an all-girl string ensemble that had a concert the next day, and I found myself wondering “where am I?” You walk out of the church having heard Mozart, Beethoven and Bach and you immediately hear mambo, bolero and cha-cha-chá playing in the bar next door!

This has become my mission – I was so impressed with the standard of classical music that was going on there. They have fantastic training; they can all do perfect solfege, they all have amazing understanding of harmony and orchestration which they also learn, they can all arrange. It’s a really good basic training. So I really wanted to show the world that there were these classical musicians there; I made four programmes of my TV programme Sarah’s Music there, we did a whole feature on the Havana Horns, and now every horn player knows that there is an ensemble called the Havana Horns now (and they were marvellous on the recording).

Where should people look if their interest has been piqued by this album and they want to find out more about classical music in Cuba?

Well, they should keep an eye on the Havana Lyceum Orchestra; they should definitely watch the documentary film that we made, which is out online now, it’s called Mozart y Mambo: A Cuban Journey. . And there you really get a little bit more background about what it’s like in Cuba for classical musicians.

I should mention that part of the proceeds from this recording are going towards raising money to buy instruments for them, because they are amazing musicians but they play on instruments that are sometimes just absolutely dreadful. It just breaks my heart to see such great musicians with such terrible instruments! The instruments are a bit like those famous old-timer cars. They are amazingly beautiful, but if you’re sitting in one you often can’t open the door because there’s no door handle, or you can’t roll the window down because there’s no handle for that – or there’s no window! – or you can see the ground below the floor. They’re polished and put together, tied together sometimes, within an inch of their lives. It’s exactly the same with their instruments; I was giving a class and I wanted to show one of the horn players something, and I picked up her horn and it came apart in my hand! I was terribly apologetic, but she said “oh, it doesn’t matter, it happens all the time”, and took her scrunchie out of her hair and tied the instrument back together with it. So I decided: I’m going to get that girl a new horn. We have a donation page for it, if people want to donate – or they can just buy the recording.

All the trade troubles, and the embargo, which is why those old-fashioned cars are so common because they simply can’t get newer ones or replacement parts, apply equally to instruments. They’re handed down from one musician to another, which means that the beginners have the most unbelievably challenging instruments ever – I find it incredible that they even persevere as horn players at all! I remember getting my first lacquered horn and I was so proud; it was so beautiful and pretty and I just wanted to practise it all day long, but some of these kids have horns that have to be seen to be believed. And if they can get new instruments I know they’ll get handed down to the next generation. In Cuba you take good care of what you have because you never know when the next one’s going to come along.

Donations for Sarah’s ‘Instruments for Cuba’ initiative can be made at https://sarah-willis.com/instruments-for-cuba

Sarah Willis (horn), Havana Horns, Havana Lyceum Orchestra, José Antonio Méndez Padrón

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC