Interview,

Alan George on Shostakovich's String Quartets

The Fitzwilliam Quartet turns 50 this year, and are marking the milestone with a retrospective look at some of the repertoire that has helped to define them - revisiting the late string quartets of Shostakovich. The Quartet's relationship with the Russian composer during his lifetime was a uniquely close one, with Shostakovich corresponding in some detail with its members.

The Fitzwilliam Quartet turns 50 this year, and are marking the milestone with a retrospective look at some of the repertoire that has helped to define them - revisiting the late string quartets of Shostakovich. The Quartet's relationship with the Russian composer during his lifetime was a uniquely close one, with Shostakovich corresponding in some detail with its members.

I was lucky enough to be able to catch up with founder-member and violist Alan George to talk about Shostakovich, the changing lineup of the Fitzwilliam Quartet's musicians over the years, and the future...

The Fitzwilliam Quartet has always been associated particularly strongly with the music of Shostakovich. Can you tell us a little about how this connection first came about?

The Shostakovich connection goes back to our first year in Cambridge; those of us who were there then as students gave our first public concert outside Cambridge in June 1969, which saw us playing No. 8. This was kind of on the cards from the beginning; three of us were in the National Youth Orchestra, and got together to form a string quartet in Cambridge as soon as we arrived. We were all violinists, so I had to change to the viola! We’d done the Tenth Symphony in our last concert with the NYO and it rather infected us, so playing the quartets seemed the natural thing. So after that, while still at Cambridge, we just learned a few more; hardly any of them were played in the West apart from No. 8. We were so lucky to be able to go straight from undergrads at Cambridge to being the Quartet in Residence at the University of York, and we brought it all up here with us.

There used to be a place called the Anglo-Russian Music Shop, next to Foyle’s, and one day I saw an LP of Quartet No. 13, which I had no idea existed; I bought it and listened to it, and it just blew me away, so we decided we’d like to play it. But there wasn’t any music available, so a good student friend of mine (the writer Erik Levi) suggested that we write to Shostakovich. I got an immediate reply from him saying that when he got back to Moscow he would send the music and that he was going to be back in England in November, so if it happened then he would come to hear it. It was really rather a bombshell – we had had no expectation of anything like that, as I didn’t even know that he was coming back to Britain again. Sure enough, a few weeks later the music arrived with another letter, saying he still hoped to be able to come. I had a phone call from the Hochhausers, who were managing him at the time, informing me what train he was going to be on and what kind of accommodation he’d need; we got the university to fix everything up and I went and met him from the train, and it was as straightforward as that! It was unbelievable, life-changing in a way. Every time I walk to the station it keeps that memory fresh: I don’t go up to the university that much any more, but just being in that hall is enough for me to picture exactly where he sat.

And it all developed from there; Decca wanted us to go on and record the whole lot, and I’m glad to say the recordings did get a bit better over the course of that project and we got some very good reviews which led to the label asking us to do even more. In many ways we were running before we could walk; we’d come out of Cambridge and gone straight into this amazing residency at York that had enabled us to rehearse, do concerts and find our feet; but with the Decca contract under our belts we were always struggling to keep up, both with the recordings and with the reputation we were forming. It was quite tough, actually, and it put a lot of strain on us for a while. But the origin of it all was just being in the right place at the right time.

The membership of the Quartet has evolved over the years – how would you say this has affected the sound?

When we got to York, part of the residency deal was that there was a grant for us to go and study with whoever we wanted to, so for three years we went to London every Monday on the train to Sidney Griller at the Royal Academy, and he was a mentor, a father-figure and more. He produced five or six quartets around that time – the Lindsays, the Albernis, ourselves, the Medicis, the Coull Quartet, and the Bochmann. We were just part of his production-line in a way, though I think we kept more in touch with him, and stuck with his teachings longer than some of the others. One of the principles he kept banging into us is that a quartet is its four members, and you have to acquire techniques to play in a quartet, and so on – he was very hardline on this. Apart from the very beginning when they were students and one or two people didn’t quite work out, his own quartet stayed the same all through their lives, as did the Amadeus. As soon as somebody died, both those quartets finished (in both cases, as it happens, it was the viola player…).

To answer the question in a roundabout way… A year or two ago I was playing a CD of something, and my son Jacob, who is a fantastic fiddle-player in his own right, commented that he thought Chris [Rowland] sounded amazing on the recording; but it wasn’t Chris at all, it was Lucy Russell! Which rather demonstrates that the quartet, as it is, has somewhat inherited that old sound and the older tradition, and that same attitude to playing. It’s not identical, of course, with different players, but it all comes from the same stable. And somehow or other, a lot of that style from the ‘80s has reinvented itself in the last twenty years or so.

Some composers’ string quartets fall neatly into sets, or even constitute some kind of overarching cycle in their own right. Do you think this is the case for Shostakovich, or are the quartets more self-contained?

Well, it’s a bit of both. They are far more of a coherent unit than almost any other set, except maybe the Bartók quartets – because you can hear in Bartók that development from one to the next. With Beethoven, for instance, they basically come in three batches, and it’s not really a cycle at all; he certainly didn’t think of it that way. You have the early, the middle and the late sets, and each of those has developed based on what he was writing in between. With the Shostakovich quartets there is no 'early' set, because he didn’t start writing them until he was into his thirties, so we’ve only got the middle and the late periods, as it were. There is a cyclic element: from No. 7 onwards, or thereabouts, he realised that they’d all been in different keys so far, so he then set out to complete a cycle of 24 all in different keys. But this was something that was introduced along the way rather than having been the idea from the outset – I’m not sure exactly at what point he realised that that was something he could do (and of course he did end up rather short of 24 in the end).

They do have different personalities, one after the other, until you get to No. 12, which is a radical change. At that point, after No. 11, he’d had a serious heart attack and it was touch-and-go whether he’d survive, which affected the colour of just about everything he wrote after that - not just the quartets but the last two symphonies, the sonatas for violin and viola, and the last couple of song-cycles. The last four quartets are all completely different from each other, of course: they’re not all totally obsessed with death, but there’s certainly that overriding sense of mortality. There’s also the use of twelve-note rows, which started with the Violin Sonata. There is certainly a sense of the last quartets standing apart.

Here Shostakovich is getting to the point where his harmonic language is so very chromatic: officially he’d decried Schoenberg’s twelve-tone method, though he adored and revered Alban Berg, and some of his tone-rows (like the beginning of Quartet No. 13) are really quite tonal, like the opening of the Berg Violin Concerto, with thirds and scales. That kind of much newer, at times atonal language, but still within a context of tonality, creates this tussle going on between tone-rows and diatonic melodies. No. 12 in particular is really invigorating from that point of view.

Can you tell us anything about the Fitzwilliam Quartet’s future plans?

We’ve already got sessions booked to do the Schubert C minor and G major Quartets (on gut strings, to go with the A minor and D minor, out in February); we’ve had Schubert coming out of our ears! As for Beethoven, we’d previously taken a slight sabbatical from him: Jonathan, our second fiddle player, got to the point where he simply refused to play any more, because he found it too stressful. This is Jonathan through and through, endearingly eccentric as ever: the only piece by Beethoven he would play was the Grosse Fuge! So we did that every now and then; but then when Jonathan retired, we got down to it again. This was partly encouraged by Richard Wigmore, because we present these study sessions with him in Cambridge – two a year there, and one in Hay on Wye – and he has his clientele who come year after year after year. We’ve been doing these for about ten years now. And of course you have to have different repertoire for each session, which has been quite demanding! We started off doing a bit of Haydn and Mozart, and then working through the Beethoven and the last Schubert quartets, so we had no choice – and it really got us going, so we had Beethoven coming out of ears for a while as well.

Whether or not I’ll be able to stay around long enough to get any of the Beethoven quartets recorded on gut, I don’t know: we planned to record three of them, but then we were nudged towards Schubert rather than Beethoven. I know everybody does it, and everybody’s going to be doing Beethoven next year, so we might just back off a bit. It really is a huge task!

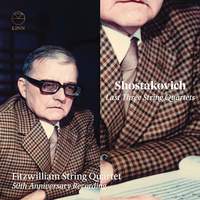

The Fitzwilliam Quartet celebrate their 50th anniversary by returning to the repertoire that made their name - revisiting Shostakovich's enigmatic late quartets.

Available Formats: 2 CDs, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC