Interview,

David Skinner on Praetorius

A linchpin of the renowned English early music community, vocal consort Alamire draws on the extensive musicological experience of its artistic director David Skinner to produce programmes with an engaging narrative - most notably their recent album 'The Spy's Choirbook', a selection of music from a musical collection compiled by Petrus Alamire, who spent part of his colourful career as a spy both for and against Henry VIII.

A linchpin of the renowned English early music community, vocal consort Alamire draws on the extensive musicological experience of its artistic director David Skinner to produce programmes with an engaging narrative - most notably their recent album 'The Spy's Choirbook', a selection of music from a musical collection compiled by Petrus Alamire, who spent part of his colourful career as a spy both for and against Henry VIII.

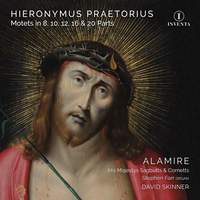

Their latest recording has no such skulduggerous connection, focusing rather on the polychoral works of North Germany's Hieronymous Praetorius - music of breadth and majesty on a par with the better-known Gabrieli style from Italy. I spoke to David about how this album came to be, and what sets Praetorius apart from his contemporaries.

You refer in the notes to this album to the different ways the Venetian style crossed over into Germany; the Southern Germans such as Hassler being able to learn from masters such as the Gabrielis in person, while further North such music was only disseminated in print. Do you think this extra distance (literally and metaphorically) affected the way the North German polychoral style developed?

It’s difficult to say. Distance and local custom could be a factor, but musicians working at this level would have been well aware of practices elsewhere. Printed music at this time was widely circulated, so access to the likes of Lassus and others would have been relatively straight forward. In the case of Hieronymus, while he spent the majority of his life in and around Hamburg, we know that at least once he met with other polychoral masters. This happened in 1595, when he was invited to the extraordinary Gröningen organ examination; here he met Hassler and Michael Praetorius (no relation). Undoubted the event made a lasting impression on Heironymus, which went on to influence his some 100 published works in German and Latin between 1599 and 1625. there is so much more here to explore.

Some of these works have bass parts extending far down into the depths, with pedal B flats that one might normally associate with the oktavist tradition and works such as Rachmaninov’s Vespers. Was this style of singing in fact more widespread than the popular Russocentric stereotype would suggest?

The vocal range of a renaissance choir was probably no different to that of a modern choir, give or take a tone or semitone in either direction. In the end the canvass would include the typical five general voice types of soprano, alto, tenor, baritone and bass, and one could imagine that this normally (in a capella performace) would range from a low bass F to a high soprano G or A. The presence of low B flats is therefore good evidence that these parts were likely to be performed by instruments. For our recording with cornets and sackbuts, this low part was taken by bass trombones in F. The vast textures of Heironymus’s larger polychoral works really does demand instrumental support, not only for the depths of the lowest choir, but to the heights of some of the treble parts which frequently ascend to top As. What is particularly magical here, with the right musicians, is the sublime blend between a high soprano voice and a cornet creating a warm and vibrant tone.

The music recorded here is clearly every bit as majestic and finely-crafted as anything from Gabrieli or Schütz, yet Praetorius’ reputation has tended to lag behind those of his contemporaries. Why do you think this is?

A very good question, and one that I’ve asked myself for many years! Of course his 8-part motets and Magnificats have made it on to past and recent recordings, many of them very fine indeed. But these tended to feature voices only, either choral or solo consort. In order to realise Heironymus’s larger-scale works from 10 to 20 parts, obviously many more singers are required as well as instruments and organ continuo. Each motet has its own individual scoring and ranges: two choirs of five parts, four choirs of four parts, five choirs of five parts, a choir of low voices pitted against a choir of high voices, etc. So many possibilities and so many combinations. While the result is indeed majestic it’s interesting to note that the music itself is relatively easy to sing and play. The only practical issue — and one that may have played a part in his relative obscurity in the past — is the sheer expense of production. Alamire certainly stretch its forces for this project, normally being used to repertoire requiring five to 14 singers. For Praetorius we stretched to 20 singers and 10 instrumentalists, which was glorious to behold in the flesh.

For a German Protestant composer, Praetorius seems to have been unusual in writing a substantial amount of sacred music in Latin, a language generally eschewed by his contemporaries both in Germany and across Protestant Europe. How much significance do you think we should ascribe to this decision?

In protestant Germany, like Elizabethan and Jacobean England, there was nothing offensive in music being set to Latin. It wasn’t the language that was at issue, but the content. Biblical texts, especially from the Psalter, were the staple fare while Catholic texts venerating the Virgin and Saints would have been far less appropriate.

In music of this kind the line between a vocal and an instrumental line is often blurred, with doubling or reassignment of parts commonplace. How much leeway did you have (or allow yourself…) in experimenting with sonic combinations within these rich textures?

There are many ways in which each of the motets we recording might have been realised. Indeed in his Syntama musicum (1614-20), Michael Praetorius describes up to 12 principal styles of performance options for such music. While we opted for various combinations of voices, cornets, sackbuts and organ — the scoring of each being highly mindful of clarity of text declamation — we could have used various combinations of practically any instrument in common use at the time be they plucked, bowed or blown. In the end, like all of our projects (and surely as it would have been in Praetorius’s time) we were working within the confines of a set budget. I would imagine that in the early 17th century performances of multi-choir works in a large provincial church verses those in a grand royal or noble occasion would have been markedly different. I suppose one can argue that we took the high to middle ground, and one that might have been most common at the time.

Alamire has hitherto recorded for Obsidian Records, with five previous albums of Renaissance music available on this label. What led you to set up your own label, Inventa Records, which you’re launching with this recording?

In fact Alamire recorded 10 projects with Obsidian Records, which was founded by my dear friend Martin Souter in 2007 in order to create a recording platform for Alamire (founded in 2005). Much thought, care and passion went into every project and we always did the editing together: Martin on the computer and me wearing the cans. Martin died in September 2014, the month in which our Spy’s Choirbook was released which went on to win a Gramophone Award. It was the start of our trilogy commemorating Henry VIII’s three musical queens. The second was Anne Boleyn’s Songbook (2015) while the last was Thomas Tallis Songs of Reformation (2017). This seemed a good time start something new, and it has been great to work with Adam Binks of Resonus Classics to create the latest label dedicated to the research and continued proliferation of early music, and I look forward to seeing what the future holds for Alamire and our specialised projects. Certainly there are still many ideas waiting in the wings!

Stephen Farr (organ), Alamire, His Majestys Sagbutts & Cornetts, David Skinner

Available Formats: 2 CDs, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC