Interview,

Madeleine Mitchell on Grace Williams

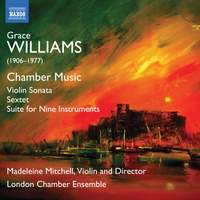

Violinist Madeleine Mitchell has always been a musical explorer, recording newly-composed works (some written for her specifically) and pieces by lesser-known British composers throughout her career. It's no surprise, then, that her latest album focuses on the compositions for violin of the twentieth-century Welsh composer Grace Williams - a pupil of Gordon Jacob, Ralph Vaughan Williams and Egon Wellesz who eschewed her native country's predominantly choral emphasis in favour of instrumental music.

Violinist Madeleine Mitchell has always been a musical explorer, recording newly-composed works (some written for her specifically) and pieces by lesser-known British composers throughout her career. It's no surprise, then, that her latest album focuses on the compositions for violin of the twentieth-century Welsh composer Grace Williams - a pupil of Gordon Jacob, Ralph Vaughan Williams and Egon Wellesz who eschewed her native country's predominantly choral emphasis in favour of instrumental music.

I spoke to Madeleine about her relationship with this music, and Williams's unique but hard-to-define musical style.

How did you first come across Williams’s music yourself, and what factors led to this fascinating album which draws together some very varied examples of her chamber output?

I knew of some of Grace Williams's orchestral works, and heard the Missa Cambrensis on BBC Radio 3 in 2016 when it was performed successfully by the BBC National of Wales and Chorus. This project began when I went to Tŷ Cerdd, the Welsh Music Information Centre in Cardiff - then run by Gwyn L Williams, formerly a BBC producer with whom I'd worked a lot. I asked to see music for violin by Welsh composers; the manuscript of Grace Williams's Violin Sonata caught my eye, and I asked if I could have a copy. Serendipitously a conference was convened in Bangor in 2017 on the fortieth anniversary of her death - the first International Women's Work in Music - and I performed the Violin Sonata with the pianist Konstantin Lapshin (who was Chappell Gold Medal winner at the Royal College of Music, where I've been a professor for many years).

The performance was very well received and set me on a path to discovering what other chamber works there were. The Piano Quintet of 1928, which awarded second place in the Cobbett Prize, is sadly lost, as is the Rhapsody for cello and piano. The British Music Society were very supportive and I was awarded a major grant, though not sufficient to record the two major chamber works - the Sextet for Oboe, Trumpet, String Trio and Piano and the Suite for Nine Instruments, so I sought further funding from the Ambache and Vaughan Williams Trusts. I assembled a marvellous group of colleagues under the auspices of my London Chamber Ensemble, and was given invaluable support in kind by being able to record at City University Performance Space and the Tŷ Cerdd studio in Cardiff. The three short pieces, for players with our instrumentation, complemented the three substantial works.

Although her voice is distinctive, naturally it’s possible to hear the influences of various other composers in Williams’s music – Bartók, Shostakovich and others. Where do you feel her compositional style sits in relation to her contemporaries?

The three major chamber works we’ve recorded are relatively early works, written when Grace Williams was aged 24-26. I think in the Violin Sonata one hears the influence of her teacher Vaughan Williams in the glorious slow movement with the folk-like theme and the pentatonic scale. She wrote the work whilst in Vienna, studying with Egon Wellesz on a travelling scholarship which Vaughan Williams had helped her obtain (revising the first movement in 1938 when she was back in London). She went to the opera almost every night, and would have heard music from central Europe. I do think hers is a strong personal voice, influenced by her Welsh roots. The slow movement of her Sextet of 1931 featuring the trumpet (her favourite instrument) does have similarities with Britten, but came before much of his work. By the time she wrote the Suite for Nine Instruments in 1934, however, she had developed a more modernistic style, rather minimalist (over thirty years before Michael Nyman coined the phrase) in that she employs the tritone B-F throughout most of the work.

Although there are only six works on this album, they span Williams’s career; the three most substantial ones are all from the 1930s and there’s quite a difference in style between these and the smaller, later works. Do you think she consciously struck out in a new direction at some point, or is this just the natural evolution over time of her compositional voice?

Grace Williams was a practical and versatile composer. She was already accompanying her father's choir on the piano whilst she was at school. She wrote on the manuscript of her short Romanza for Oboe and Clarinet, from the 1940s: 'pastiche but nice'. The Sarabande for Piano Left Hand of 1958 was written for her friend Eluned Davies, who lost the use of her right arm for a while. The Rondo for Dancing for two violins and optional cello (or double bass or piano accompaniment) was written in 1970 specifically as a teaching piece in an album published by the Welsh Guild for Music. She was also the first woman to write music for a film, The Blue Scar in 1949.

Williams marked many of her own works as ‘not worth performing’ – less extreme than Sibelius’s famous burning of manuscripts, but still significant. Do you think we go against the composer’s wishes when we subsequently revive and perform works that they themselves withdrew?

It’s a very interesting question. I wouldn’t say she ‘withdrew’ her manuscripts - with the Violin Sonata, Grace Williams wrote ‘second movement worth performing, outer movts not good enough’ on the title-page when revisiting her manuscripts in 1957. Knowing that the composer was very self-critical and tended to be rather depressive, I feel one has to make an executive decision to give people a chance to decide if they agree! I consulted the Grace Williams Estate and her niece, who was enthusiastic about my project.

Why do you think Williams’s reputation has tended to lag behind that of composers such as Maconchy or in particular Britten, both of whom she studied alongside?

She didn’t push herself forward at all or have influential connections; nor did she have an effective publisher like Britten, and it was generally more difficult for women in those days. These chamber works were unpublished, and I obtained copies of the manuscripts from the National Library of Wales. She was a very respected musician, but seemed to be almost self-denigrating. She turned down an OBE later on, wasn't ambitious, and the disastrous first performance of her major work the Missa Cambrensis must have been so disappointing for her. I do hope through this project we have been able to bring this work to the public she deserves.

Madeleine Mitchell (violin), London Chamber Ensemble

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC