Interview,

Bantock's Omar Khayyám on Lyrita

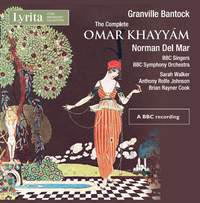

Granville Bantock's 'exotic' epic Omar Khayyám was surely one of the most remarkable English choral works of the early twentieth century: setting a selection of Edward FitzGerald's translation of the works of the eponymous eleventh-century Persian poet, it's scored for a vast orchestra including quadruple wind and double strings, and clocks in at nearly three hours. Despite its popularity with choral societies and festivals in the first half of the century, it rather fell off the radar after the composer's death, only receiving its debut outing (and that in truncated form) on CD in 2007. However, its first radio broadcast (from 1979) has recently been issued on Lyrita and presents the work in its entirety.

Granville Bantock's 'exotic' epic Omar Khayyám was surely one of the most remarkable English choral works of the early twentieth century: setting a selection of Edward FitzGerald's translation of the works of the eponymous eleventh-century Persian poet, it's scored for a vast orchestra including quadruple wind and double strings, and clocks in at nearly three hours. Despite its popularity with choral societies and festivals in the first half of the century, it rather fell off the radar after the composer's death, only receiving its debut outing (and that in truncated form) on CD in 2007. However, its first radio broadcast (from 1979) has recently been issued on Lyrita and presents the work in its entirety.

I spoke to Adrian Farmer of the Lyrita Recorded Edition Trust recently to find out more…

Omar Khayyám’s been recorded once before, with the BBC Symphony Orchestra under Vernon Handley on Chandos: how does the newly-released recording differ from that earlier one?

For some reason, they cut 20 minutes from the score - mostly chorus material. It gives the impression that this was some sort of authorised shortening by Bantock himself, because perhaps in some performances it was too long. I’ve certainly never come across any version of the score like that, but comparing the recording with the full score you can see very clearly where cuts have been made. That’s all completely restored and included in the version we’ve just put out.

Are there any significant differences between Del Mar and Handley in terms of performance style?

One of the confusing things when I first listened to the Del Mar version was that he’s within a few seconds of the playing time on the Chandos version – however, it’s got that extra 20 minutes of music! What it does tells you is that Del Mar whips through the piece with more pace and vigour than Todd [Handley] – it’s really very astonishing that he could make up the time to include that.

What excites you about the piece itself?

I came from a position of not knowing the piece at all. When we found it in the archives and decided to transfer it, I was initially rather sceptical, because big Victorian choral pieces like this can be a bit of a bore! But I have to say that the first time I heard it I was completely converted. Bantock is the most extraordinarily successful big dramatic composer – he knows exactly how to pace these huge works, how to vary the texture…The choral writing is powerful not particularly complex, so the choirs are obviously going to have a ball. He was just very, very good at that type of thing, and his personal selection of verses from Omar Khayyám makes for a very convincing dramatic experience. So yes, put me down as a reformed Bantock sceptic!

So why has Omar Khayyám fallen out of fashion, do you think? Is it down to its sheer scale, or the musical language itself?

I don’t think it can be the musical language itself, because after all we’re perfectly happy with Elgar: people still flock to hear Gerontius, and all sorts of other huge choral pieces! And the time-lapse between Elgar and Bantock is not very long. And it can’t be the texts because Omar Khayyám has been one of the longest-lived, most exploited texts in history. I think it’s Bantock himself – I think there’s a certain perception of his music that’s relegated him to the second tier, which is a shame.

But the scale of the piece is an absolute barrier! Although in itself it wouldn’t present many technical problems at all for a twenty-first century orchestra and chorus, the problem is that it’s completely through-composed. It doesn’t stop, and you find that within as little as twenty bars there can be several changes of key-signature and tempo. The level of concentration required on the part of the conductor and all the performers is immense. It’s not like performing something like the Verdi Requiem, where you have self-contained sections: each of Omar's three parts is absolutely continuous! It’s an extremely fluid work, in an unusual compositional style that is more akin to late nineteenth- century German opera than to English Oratorio.

What else is in Lyrita’s immediate future in terms of new release?

We’ve transferred 104 discs-worth so far, and we’ve only just started to scratch the surface…! There are two things I can mention – in October we’re bringing out a recording of Humphrey Searle’s Symphonies Nos. 3 & 5, which I don’t think have ever been recorded before, plus a couple of his orchestral works. That will definitely appeal to people who are interested in music from the 1960s and 70s in the UK, I think: Searle is basically a serialist composer, but within a British framework rather than a central European one. And then finally, after 80-odd years, we have the first recording of Bernard van Dieren’s Chinese Symphony – it’s conducted by William Boughton, and we recorded it with the BBC National Orchestra of Wales in Cardiff. It’s a grand work for full orchestra, chorus and five vocal soloists: curious music-lovers have long wondered what it sounds like and soon they’ll get the chance to find out!

Sarah Walker (contralto), Anthony Rolfe Johnson (tenor) & Brian Raynor Cook (baritone), BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, Norman Del Mar

Available Formats: 4 CDs, MP3, FLAC