Interview,

John Corigliano - The Ghosts of Versailles

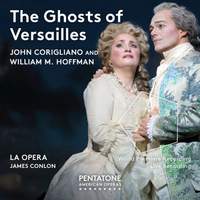

When our friends at Pentatone told me in December that John Corigliano's The Ghosts of Versailles (premiered in 1991) was finally getting its first outing on CD, I felt like Christmas had come early: I've loved this extravagant, madcap 'grand opera buffa' ever since my Presto colleague James introduced me to it about ten years ago via an old VHS tape of the original Metropolitan Opera production (starring Teresa Stratas, Marilyn Horne, Susan Graham and Renée Fleming, among others). I think said introduction came about because I was waxing lyrical about my love for two of my favourite operas, Le nozze di Figaro and Il Barbiere di Siviglia (both based on dramas by Pierre Beaumarchais), and lamenting the fact that there wasn't a major operatic setting of the third play in Beaumarchais's 'Figaro trilogy', La Mère coupable, which follows the fortunes of Figaro and Suzanne/Susanna, the Count and Countess Almaviva and their illegitimate children during the French Revolution. It turned out that Corigliano and his librettist William M. Hoffmann had not only granted my wish but taken it one step further by setting the action of La Mère coupable as a play-within-a-play, conjured up by the ghost of Beaumarchais for the ghost of Marie Antoinette as they languish in the theatre of Versailles (and the afterlife!) in the wake of the guillotine.

When our friends at Pentatone told me in December that John Corigliano's The Ghosts of Versailles (premiered in 1991) was finally getting its first outing on CD, I felt like Christmas had come early: I've loved this extravagant, madcap 'grand opera buffa' ever since my Presto colleague James introduced me to it about ten years ago via an old VHS tape of the original Metropolitan Opera production (starring Teresa Stratas, Marilyn Horne, Susan Graham and Renée Fleming, among others). I think said introduction came about because I was waxing lyrical about my love for two of my favourite operas, Le nozze di Figaro and Il Barbiere di Siviglia (both based on dramas by Pierre Beaumarchais), and lamenting the fact that there wasn't a major operatic setting of the third play in Beaumarchais's 'Figaro trilogy', La Mère coupable, which follows the fortunes of Figaro and Suzanne/Susanna, the Count and Countess Almaviva and their illegitimate children during the French Revolution. It turned out that Corigliano and his librettist William M. Hoffmann had not only granted my wish but taken it one step further by setting the action of La Mère coupable as a play-within-a-play, conjured up by the ghost of Beaumarchais for the ghost of Marie Antoinette as they languish in the theatre of Versailles (and the afterlife!) in the wake of the guillotine.

When the new recording finally arrived and I put it on in the office, those who hadn't heard the work before were soon smiling in delight as snatches of Figaro and Barber emerged from the weird and wonderful world of smoke and mirrors which Corigliano creates for the ghosts, and nodding along to the affectionate (and maddingly catchy!) pastiches of Rossini's patter-arias and Mozart's glorious operatic ensembles. It was a real pleasure to chat to the composer from his home in New York on Friday to dig a bit deeper into the genesis of Ghosts and to find out a little more about how this long-overdue recording finally came about…

Did you set out to write a straightforward completion of the Beaumarchais trilogy, or was the framing device of the ghosts there from the start?

The framing device was not thought of at all! The first thought I had was to get my librettist William M. Hoffmann (who speaks French very well and knows these plays) to read and translate the Beaumarchais play (there was no existing English translation) and to do it like The Marriage of Figaro and The Barber of Seville – but also sort of like The Rake’s Progress, using techniques that are contemporary but with musical material in the spirit of the old plays. But when we deciphered the text, we found that it just wasn’t a very good play! And this posed a problem for us, because we loved the characters. There’s Bégearss, this villain who’s a revolutionary posing as a friend to the Almaviva family and especially to the children - to Léon, who is a product of the famous seduction of Rosina [the Countess] by Cherubino, and to Florestine, who is the illegitimate daughter of the Count with some unknown woman. And these two are in love with each other (they’re not actually related, they have completely different parents!), and the Count doesn’t want to allow the marriage, and that was the conflict that we wanted to see. But I didn’t want to write The Rake’s Progress – neo-Classicism is a wonderful thing, and in my youth I wrote that way, but [by the time of starting work on Ghosts) my vision had changed and I had ways of writing that are more contemporary and I think more interesting to me, exploring sonority and sound. So I said to Bill: ‘Can you come up with some setting for this play we’re going write that is in flux, that has no time?’ And he thought about it, and he came back to me and said ‘Well, there are two ways we can do this – we can set it in the world of dreams, or we can set it in the world of ghosts’.

And the idea of the ghosts won, because I wanted to write music of a certain nature. Then the logical thing was to have Beaumarchais as a ghost, alongside his own characters living in this ghost world - and it’s logical that Marie Antoinette is involved because Beaumarchais really DID know Marie Antoinette, from the theatre. One of the last things she did was The Marriage of Figaro, and she was one of the people who convinced the King not to suppress it). So we fictionalised a love-affair between them…well, not strictly a love-affair: Beaumarchais was in love with Marie Antoinette, and Marie Antoinette was desiring to not have her head cut off, so his role as a ghost was to essentially change history and keep her alive.

Bill’s idea gave me the opportunity to create a sonic world of ghosts, just as I created a sonic world for the eighteenth-century characters. The image you should have is of cigarette-smoke - it goes up, it swirls, it becomes thicker, then it becomes invisible. So what the drama became was slightly different from what we started out with. It was two stories, really: it was a story of love set in the world of ghosts (Beaumarchais’s love for the queen), and it was also the story of freeing the queen within the play, set in the 18th century because La Mère Coupable is set in the French Revolution, with the whole Almaviva family living in Paris. It felt very natural to us to also have a plot where Figaro would try to steal a particular necklace from the Turkish embassy and all that sort of convoluted business, and to have all of that going on whilst Beaumarchais is courting Marie Antoinette, who is oblivious to it all at first and then becomes more and more entrapped by it.

You’ve mentioned Stravinsky’s The Rake’s Progress in relation to the music for the play-within-the-play – were there any twentieth-century operas which influenced you when it came to creating the sound-world for the ghosts?

No, not at all! I actually created it by literally sketching out what I thought it should be, then to take coloured pencils and draw a world of smoke: there’d be a block of color (pictured in music by a chord or cluster of a choir of the orchestra, say the woodwinds) and it would little by little disappear and slide down and to another block of a different color, (say the strings,) which would slide into another sonority, and so on - I wanted to create that world, a world of smoke and flux.

So at the beginning of the opera, I created these single chromatic line of ‘cigarette smoke’ played by a synthesizer, very, very quietly - then gradually introducing eight instruments that at any time can double the synthesizer, taking the sound over, and slowly crescendo to from piano and then diminuendo to niente ad lib. l’d take a little of that chromatic line , and change the sound to a clarinet, or to a flute, or a violin. Like smoke changes shapes as it rises. And by doing that I created a line (it’s actually a twelve-tone row) that’s constantly changing color.

In terms of harmony, I took four chords, none of which have the same notes in them. This meant that you could float one into the other because they had no notes in common…So the whole idea was that you have one chord, then another that will just wipe through that chord, and that chord would disappear.

The original production of the opera at the Met had a very starry line-up of singers indeed – did you have these specific voices in mind when you started writing, or were the roles cast further down the line?

Well, that’s a very strange story, because I had images of people I wanted - and every one of them either died or stopped singing! Donald Gramm was the Beaumarchais I had in mind, and he died whilst I was working on the piece, I read it in the paper. Then there was a fabulous old tenor, James McCracken, and he was my Bégearss, and he also died; the singer who replaced him, Graham Clark, was tiny and acrobatic, and just exactly the opposite of what I’d imagined - but he had the voice for it, kind of a heldentenor, and he did a fantastic job. Quite amazing.

Did you revise the score very much for the Los Angeles Opera production from which this recording was made? The scene in the Turkish Embassy, for instance, which was originally sung by Marilyn Horne, and features a musical theatre star this time around…

No, I didn’t change much at all, and they were such wonderful singers - Bégearss was just terrific and Figaro was amazing! There was so much energy coming off the stage

The Turkish Embassy scene actually comes from the end of Act One of [Rossini's] L’Italiana in Algeri; I love the joy and insanity of that! I mean, people are dancing around in the audience because the energy-level is so high and Rossini goes beyond words, beyond patter, into all these funny sounds…the orchestra are playing away and it gets wilder and wilder and wilder, and I said to Bill ‘We have to end Act One in the Turkish Embassy in Paris - it’s the only way to do it!’ I wanted that kind of anarchic, wild music, that kind of excitement.

Patti LuPone took this on [in the LA production], and I thought I’d rewrite it for her, make it a real Patti LuPone piece, but she was determined to sing it the way it was - and she really could do it! For a show-singer, it’s really unheard of to get the chest-voice up as high as she did - she sang it as a real operatic mezzo.

How did this first recording of the work come into being, fifteen years after the premiere?

It was a favourite piece of Gordon Getty, after he saw it in Evanston, Illinois - they have a music school with a huge opera department there and they did Ghosts, and afterwards he came over to me and said ‘Come out and have some to dinner - I want to thank you for what a great opera you’ve written!’. He told me that he wanted to establish a new series of American operas on record, and I suggested Ghosts, and he said ‘But Ghosts is already recorded!’. And I said ‘No it’s not! There’s this DVD of it [from The Metropolitan Opera, only available as part of a boxed set], but there’s no audio recording’, and he jumped up and down and said ‘Well there’s gonna be one now!’! And before I knew it, it was all taken care of, and I am SO grateful to him. He’s also recorded Jennifer Higdon’s opera Cold Mountain, which is a wonderful work. Getty is really a remarkable man: it’s a great idea because opera is so expensive to record, and recording it is so rare. So to do this for American opera is fantastic.

Will you write any more opera?

I’m just orchestrating one! It’s my second, and probably my last, because I’m 78 years old now – and they take so long! It’s rather wild, and I wouldn’t want to go into too much detail just yet, but it’s called The Lord of Cries, and it’s a combination of two completely opposite fictional things…but when you follow the storyline and the characters, you see that they’re not opposite at all. It is a wild and passionate love story with a horrifying Greek tragic ending.

The Ghosts of Versailles was released on Friday on Pentatone, starring Patricia Racette as Marie Antoinette, Christopher Maltman as Beaumarchais, Lucas Meachem as Figaro and Robert Brubaker as Begearss.

Available Formats: 2 SACDs, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC