Artist Profile,

Jimmy Smith

All of that John Zorn last week gave me the heebie-jeebies so I’ve retreated to one of my safe places, the world of organist Jimmy Smith, the Hammond B3 trailblazer who established the instrument as an authentic jazz instrument. Influenced by swing band Hammond innovator Wild Bill Davis, Smith dragged the B3 out of the ballroom, into the jazz club, but kept the rhythm & blues foundation, and earned his chops by playing with the toughest hard boppers.

Born in Norristown, Pennsylvania in either 1925 or 1928 (some confusion around the exact date, but not on Mars at least), by the time he was nine Smith had won a Philadelphia talent contest thanks to his boogie-woogie piano skills. ![Jimmy Smith] Jimmy Smith](https://d27t0qkxhe4r68.cloudfront.net/images/articles/smilingsmith.jpg) After serving in the Navy, Smith studied music with composer Leo Ornstein and had his first exposure to the Hammond in 1951, playing in local R’n’B bands. Blue Note owner Alfred Lion happened to hear him play in a Philadelphia club and signed him up, leading to a staggering forty-ish recording sessions for the label between 1956-64 (...how'd ya like them apples, all you 'reclusive geniuses' out there). In the sixties Smith signed to Verve and recorded some cracking sessions with plush Lalo Schifrin and Oliver Nelson big band arrangements, the classic being Nelson's majestic Walk on the Wild Side. Smith was active up until his death in 2005, recording some quality late albums like Damn! in his seventies, but most Jimmy Smith fans still rate the Blue Note sessions as the prime period, and Back at the Chicken Shack holds up with the best of them.

After serving in the Navy, Smith studied music with composer Leo Ornstein and had his first exposure to the Hammond in 1951, playing in local R’n’B bands. Blue Note owner Alfred Lion happened to hear him play in a Philadelphia club and signed him up, leading to a staggering forty-ish recording sessions for the label between 1956-64 (...how'd ya like them apples, all you 'reclusive geniuses' out there). In the sixties Smith signed to Verve and recorded some cracking sessions with plush Lalo Schifrin and Oliver Nelson big band arrangements, the classic being Nelson's majestic Walk on the Wild Side. Smith was active up until his death in 2005, recording some quality late albums like Damn! in his seventies, but most Jimmy Smith fans still rate the Blue Note sessions as the prime period, and Back at the Chicken Shack holds up with the best of them.

![B3 and Leslie Cabinet] B3 and Leslie Cabinet](https://d27t0qkxhe4r68.cloudfront.net/images/articles/hammond.jpg) At this juncture it’s worth having a quick look into the origins of the Hammond B3 organ, to better understand how an instrument designed to accompany hymns became the slinky sound of soul jazz. Invented by Laurens Hammond and John M. Hanert, the first Hammond organs went on sale in 1935. Designed to replicate the sound of a pipe organ for smaller church halls by offering similar registers, foot pedals, and many of the favourite pipe organ stops and settings, the Hammond was quickly very successful. The technology involved wasn’t new though, being derived from the Teleharmonium of 1897, invented by Thaddeus Cahill, which used revolving electric alternators to generate tones that could be transmitted over wires. It was a gargantuan piece of kit, requiring whole railway cars to transport it, and needing dangerous voltage levels to make the sounds heard, and Hammond solved this by generating the tones with a much lower voltage, and then amplifying them electronically. But how do we get to that funky B3 sound? Step-up Donald Leslie, another inventor who decided the Hammond didn’t accurately replicate the spatial characteristics of a real church organ, leading him to experiment with placing a rotating ‘baffle chamber’ in front of the speaker, essientially creating a strobing effect like a giant FX pedal, which added a whirring, vibrato effect to the speakers output. The addition of a ‘Leslie Cabinet’ to your B3 didn’t make it sound much more like a church organ, but it suddenly had a new funky vibe when played in gospel churches, or by early rhythm and blues adopters like the forementioned Wild Bill Davis. Once club owners realised that hiring a drummer and organist was cheaper than a full band (thanks to the Hammond’s foot pedals it could cover the usual upright double bass parts too) the popularity of the organ trio took off. As a side-note, Hammond didn’t take kindly to Leslie’s offers to improve his instrument and rejected any suggestion of a collaboration, even going so far as to changing the speaker connections from the Hammond to try and curb customers from buying a Leslie. So the Hammond B3 and Leslie Cabinet were always separate pieces of kit, but together they sounded so naughty. Here’s a video of a Hammond and Leslie together, in slow motion so you can see the rotating baffle chambers in action, but no need to watch the full hour and a half...

At this juncture it’s worth having a quick look into the origins of the Hammond B3 organ, to better understand how an instrument designed to accompany hymns became the slinky sound of soul jazz. Invented by Laurens Hammond and John M. Hanert, the first Hammond organs went on sale in 1935. Designed to replicate the sound of a pipe organ for smaller church halls by offering similar registers, foot pedals, and many of the favourite pipe organ stops and settings, the Hammond was quickly very successful. The technology involved wasn’t new though, being derived from the Teleharmonium of 1897, invented by Thaddeus Cahill, which used revolving electric alternators to generate tones that could be transmitted over wires. It was a gargantuan piece of kit, requiring whole railway cars to transport it, and needing dangerous voltage levels to make the sounds heard, and Hammond solved this by generating the tones with a much lower voltage, and then amplifying them electronically. But how do we get to that funky B3 sound? Step-up Donald Leslie, another inventor who decided the Hammond didn’t accurately replicate the spatial characteristics of a real church organ, leading him to experiment with placing a rotating ‘baffle chamber’ in front of the speaker, essientially creating a strobing effect like a giant FX pedal, which added a whirring, vibrato effect to the speakers output. The addition of a ‘Leslie Cabinet’ to your B3 didn’t make it sound much more like a church organ, but it suddenly had a new funky vibe when played in gospel churches, or by early rhythm and blues adopters like the forementioned Wild Bill Davis. Once club owners realised that hiring a drummer and organist was cheaper than a full band (thanks to the Hammond’s foot pedals it could cover the usual upright double bass parts too) the popularity of the organ trio took off. As a side-note, Hammond didn’t take kindly to Leslie’s offers to improve his instrument and rejected any suggestion of a collaboration, even going so far as to changing the speaker connections from the Hammond to try and curb customers from buying a Leslie. So the Hammond B3 and Leslie Cabinet were always separate pieces of kit, but together they sounded so naughty. Here’s a video of a Hammond and Leslie together, in slow motion so you can see the rotating baffle chambers in action, but no need to watch the full hour and a half...

Smith was the genius who put the B3 on a par with piano, saxophone and trumpet as an improvising instrument, able to make it sound just as organic and human via his mastery of the various stops. He perfected controlling the B3’s attack – listen to how restrained his tone is on When I Grow Too Old to Dream, especially when comping behind a Kenny Burrell or Stanley Turrentine solo, then subtly brightening the attack for his own turn in the spotlight. Or marvel at his basslines, how his feet working independently from his hands to create counter rhythms. The sidemen on this date are superb as well - Kenny Burrell’s electric guitar complements Smith’s Hammond, instruments that occupy similar tonal characteristic and yet also contrast with each other. Stanley Turrentine’s swaggering yet considered tenor sax lines are another a major factor marking Back at the Chicken Shack as a stand-out album, 'Stan-the-Man' nicely cutting through the amplified tones organ and guitar like a shaft of sunlight (best i could do, sorry).

Smith inspired a generation of players like Brother Jack McDuff, Jimmy McGriff and rock keyboardists like Jon Lord and Keith Emmerson. He also helped shape the sound of soul jazz and onwards to the acid jazz of the James Taylor Quartet. A testament to his enduring appeal is the fact that the Beastie Boys sampled large chunks from Smith’s 1972’s Root Down (And Get It) in their tribute to him Root Down.

Something for the weekend sir?

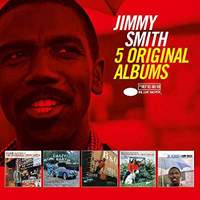

A generous five album set, this includes not only Back at the Chicken Shack but also Home Cookin' (1959), Crazy! Baby (1960), Midnight Special (1961) and Softly As A Summer Breeze (1965). Prime Blue Note era Jimmy, especially Midnight Special, recorded on the same day as Back at the Chicken Shack and just as good.

Available Format: 5 CDs

Not wanting you to overdose on Hammond (easily done, let's face it), here are some other Jimmy gems that warrant further scrutiny...