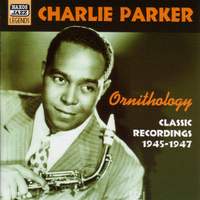

Classic Recordings,

Charlie Parker - Early Recordings

When I was a kid there was a sketch on my Muppet Show LP where Floyd, the furry beatnik sax player in the pit band, was forced to play an insultingly banal arrangement. After being threatened with dismissal for refusing to comply he muttered ‘Forgive me Charlie Parker wherever you are!’. For years I wondered who this Charlie Parker person was (in the days when t’internet was the stuff of a madman’s dreams), so revered by hipster Floyd, until years later I happened upon a Parker compilation of these early recordings in a second-hand stall at the student union bar. After decades of listening to these sessions it’s easy to forget just how bewildering and alien it sounded on first encounter, but also how compelling, and it got me hooked on jazz.

When I was a kid there was a sketch on my Muppet Show LP where Floyd, the furry beatnik sax player in the pit band, was forced to play an insultingly banal arrangement. After being threatened with dismissal for refusing to comply he muttered ‘Forgive me Charlie Parker wherever you are!’. For years I wondered who this Charlie Parker person was (in the days when t’internet was the stuff of a madman’s dreams), so revered by hipster Floyd, until years later I happened upon a Parker compilation of these early recordings in a second-hand stall at the student union bar. After decades of listening to these sessions it’s easy to forget just how bewildering and alien it sounded on first encounter, but also how compelling, and it got me hooked on jazz.

There seems to be a general consensus as to the handful of absolute geniuses in jazz, the innovators who changed the music; Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington from the pre-war generation, followed by Parker, Thelonious Monk, Miles Davis, John Coltrane and Ornette Coleman from the modern era. Parker represents the pivotal point at which jazz self-consciously becomes art music, and these recordings are the big bang from which all modern jazz springs. It can be a challenge choosing a classic album where there isn’t a single definitive edition to recommend for a specific recording, a case in point being Charlie Parker’s classic sessions for Savoy and Dial from the mid-forties. This Naxos set does as good a job as any currently available of offering the best of these sessions at an attractive price, and although the sound for these sessions was always fairly rough (Max Roach’s drums suffering the most), these transfers are clean and unlike many they have bothered to include documentation about sessions and players.

A very brief history then; Charlie Parker was born in Kansas City in 1920, a city which, along with New Orleans, Chicago, and New York, was one of the creative centres in the formation of jazz. Kansas had its own particular sound, a spontaneous and gutsy take on rhythm and blues (evinced in the difference between Kansas native Count Basie’s sound and Ellington’s), no doubt helped by the fact that the city had the most relaxed licensing laws anywhere in the US, thanks to corrupt political boss Tom Pendergast, which enabled clubs to stay open through to the dawn, leaving plenty of opportunity for players like Parker to stretch out and develop their solos. Dropping out of school at 14 and switching from tenor to alto, there is the famous story of a young Parker losing his way through the chords when trying to improvise at a jam session at the Reno Club in 1936, prompting Jo Jones (Basie’s drummer) to hurl a cymbal at Parker, essentially booting him off the stage. Undeterred, Parker took this as a spur to practise harder, and was soon good enough to join the Jay McShann orchestra the following year, rapidly building up a local reputation. He made his first trip to New York in 1939, and by the early forties he was hanging out with Dizzy Gillespie, Kenny Clarke, and Thelonious Monk at Minton’s Playhouse in Harlem, an after-hours club where musicians were given free dinner and drinks in return for performing, and forming the crux of the bebop movement. Unlike the swing band circuit, with its emphasis on dancing, at Minton’s the focus was solely on the music, and the furiously paced new music being played was decidedly not for dancing.

What was is it about Parker that remains so radical? Just listen to Ko-Ko from what is argued to be the first bebop recording session, in 1945, to hear how advanced his playing was (due to the war there was a recording ban, so the formative years of bebop sadly go undocumented). After the theme (featuring a teenage Miles Davis on trumpet, Dizzy Gillespie on piano, bassist Curley Russell and Max Roach on drums), Parker launches into an extended solo at breakneck pace, navigating the numerous chord changes with a fluency and confidence that transcends anything that had been performed or recorded up until that point, and I would argue has never been topped. This was improvisation that went far beyond that of any other jazz musician, founded on a hard-won knowledge of harmony that would rival the great classical improvisers. At a time when white big band leaders were being hailed as the kings of jazz (let’s not forget that the first jazz recording was by a white Dixieland band), Parker, Gillespie et al were reclaiming jazz as the black art form, and sowing the seeds of the avant-garde of the coming decades.

When listening to Parker it’s hard to reconcile that someone so beset with personal demons (heroin and alcohol addiction fuelling repeated mental breakdowns and ultimately an early death) could create music of such joy, beauty, exhilaration and complexity. It’s timeless music, and if you haven’t ever given Parker a listen, or need a refresher, do yourself a big favour and ‘better get hit in yo’ soul’, to paraphrase another Charles.

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC

Also very much worth a listen...

A classic concert from Massey Hall in Tornonto, 1953, this features Parker, Gillespie, an inebriated Bud Powell, Max Roach, and Charles Mingus (who originally released in on his own label, Candid). It presents the bebop masters in terrific form, clearly buzzing off each other's presence.

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC

![The Quintet: Jazz At Massey Hall [Original Jazz Classics Remasters]](https://d1iiivw74516uk.cloudfront.net/eyJidWNrZXQiOiJwcmVzdG8tY292ZXItaW1hZ2VzIiwia2V5IjoiODQ5OTA0OC4xLmpwZyIsImVkaXRzIjp7InJlc2l6ZSI6eyJ3aWR0aCI6MjAwfSwianBlZyI6eyJxdWFsaXR5Ijo2NX0sInRvRm9ybWF0IjoianBlZyJ9LCJ0aW1lc3RhbXAiOjE3MDczMjA4Mjh9)