Interview,

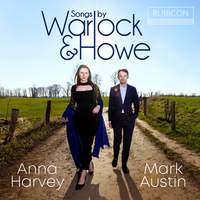

Anna Harvey and Mark Austin on the songs of Warlock and Howe

The wide-ranging gifts of Peter Warlock form the focus of a new album of song by Anna Harvey and Mark Austin, with world-premiere recordings of song-settings from the less-heard Frederick Howe (b.1951) showing the continuing legacy and influence of both Warlock and the English song tradition more generally.

The wide-ranging gifts of Peter Warlock form the focus of a new album of song by Anna Harvey and Mark Austin, with world-premiere recordings of song-settings from the less-heard Frederick Howe (b.1951) showing the continuing legacy and influence of both Warlock and the English song tradition more generally.

Anna and Mark shared some of their thoughts on how Warlock both fits into, and stands out from, that tradition, and what makes his writing for voice and piano so special.

These Warlock songs are part of a remarkable, and continuing, thread of English art song – Butterworth, Vaughan Williams, Gurney, Finzi, Roderick Williams, Ian Venables… how did this tradition arise and why do you think it has proved so successful?

Mark: The English tradition goes back many centuries, as evidenced by the wonderful lute songs of the 16th century. It’s ironic that in the 19th century, when singing in England was at its high point as a common domestic entertainment, the ballads sung did not strive to emulate German Lied in its marriage of sophisticated poetry and music. The turn towards this German tradition by composers such as Delius, Stanford, Elgar, Ethel Smyth, Elgar and others seems to have been a key factor in rekindling English art song.

The constant look to Shakespeare has proved an excellent stimulus to composers, alongside the extraordinary range of English lyric poetry. Whether the English art song can truly be called “successful”, when it remains relatively unknown outside England, is another question. It reminds me of the reputation of Thomas Hardy, whose novels are undeniably first class by any literary measure but perhaps appear parochial under international comparison with their explicit focus on rural and English contexts.

Anna: I think that the folk tradition, and the setting of traditional folk songs, has been another rich area of inspiration in English art song, and the telling of tales about people experiencing everyday English country life has also embedded the distinct English pastoral sound that is found in much of the repertoire. I agree with Mark that English art song doesn’t have the reach of that of the art songs of other countries (despite being in a language that is widely spoken), perhaps because it is seen as telling stories about a specific place and context, as opposed to expressing universal human emotions (whereas I think it also does that!).

Among so many other song-composers, what sets Warlock’s voice-setting apart?

A: The different periods of Warlock’s life and oeuvre offer a wide variety of styles and genres giving a real richness to his output — Warlock’s interest is Celtic culture was another inspiration. Warlock writes very well for the voice, contrasting songs with long legato vocal lines, and faster, wordy songs with hilarious texts, often building them to a big climax or a tender, understated ending.

M: The sheer variety of his output is unparalleled. From folk song arrangements (it is incorrect to suggest that he was not interested in folk song), to late Romantic à la early Berg, to Elizabethan pastiche with a modern colour, to simple melody and accompaniment, he asks his performers to move between styles and genres constantly. His piano parts are often tricky to play but when mastered offer a deceptive simplicity given depth by complex harmony and polyphony.

Why were the texts and musical idioms of the Tudor era so important to Warlock?

M: Warlock edited and published hundreds of lute songs (as Philip Heseltine) and was deeply immersed in this period of English music. It was inevitable that the influence would be felt in his own music. It’s possible to speculate that a past golden age attracted his rather tortured personality, in contrast to the difficulty he found in achieving happiness in the present. ‘Sleep’ is a masterpiece which creates a historical bridge from the four-part viol consort to the early 20th century. Warlock’s haunting music, which flows as if created without any metre or bar lines, is absolutely perfect.

What’s the story behind the re-fitting of new words to what became Yarmouth Fair - why didn’t the publishers want the original words (The Magpie, as you record it here for the first time) used?

M: The story goes that a roadmender named John Drinkwater had sung the tune and words of ’The Magpie’ to composer E. J. Moeran, who noted it down. Drinkwater claimed that he had found the words in an old newspaper, and the tune had simply come to him. Moeran shared it with Warlock, who arranged the song for publication, only to find that it was a duplicate of an older Music Hall song. To avoid a lawsuit, Hal Collins wrote new words for what became ‘Yarmouth Fair’. That song was first published in 1924, and the version with the original text finally saw publication in 1989.

Some of these songs are decidedly comedic, in a way that Lieder and French songs generally aren’t. Do you think they stray into what might be called “light music” – however we might define that?

A: There are many funny Lieder and French songs (Wolf and Poulenc being great examples), but if you don’t speak the language fluently the humour is perhaps not so immediate. It was very interesting performing the same songs in different countries at our launch concerts for the album. Despite having an audience who mainly had some knowledge of English in our Paris recital, the reception to Warlock’s funny, wordy songs was appreciative but muted, whereas we had some of the audience laughing out loud in our UK recitals.

M: There’s certainly comedy (‘Queen Anne’ for instance was written for children). But perhaps our experience of them in our native English amplifies this; there are humorous German Lieder (but we hear them in German) and perhaps when different national senses of humour are taken into account the difference may not be that pronounced. Warlock was certainly not averse to “light music” and many of his songs, particularly others we didn’t record would fit that category. He probably didn’t consider it a pejorative genre. Musicology has moved away from these kind of value classifications in recent years and this seems valid. Samuel Coleridge-Taylor is currently undergoing a re-evaluation and much of his music would previously have been termed “light”.

How did you encounter the music of Frederick Howe, and what’s his relationship with Warlock?

M: His daughter Flora, a fantastic musician herself, brought these folk songs to our attention a few years ago. I recognised their quality immediately. Frederick Howe has thought very deeply about how to write folk song arrangements in the 21st century that respect the original melody and words while presenting them in a harmonic language that speaks to our age. It was wonderful to record them to coincide with the composer’s 70th birthday. He cites Warlock as a profound influence, and I think the listener may detect this in the sensitive word setting and harmonic language. Pairing these two composers together has allowed their settings to reflect and enhance each other.

Anna Harvey (mezzo-soprano), Mark Austin (piano)

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC