Interview,

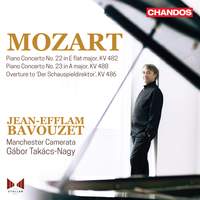

Jean-Efflam Bavouzet and Gábor Takács-Nagy on Mozart piano concertos

This year Manchester's acclaimed chamber orchestra the Manchester Camerata turns 50, and continues to settle into its new home, a converted monastery into which it moved last year. Among the anniversary celebrations, the Camerata's principal conductor Gábor Takács-Nagy has found time to continue his critically-hailed series of Mozart piano concerto recordings with Jean-Efflam Bavouzet; this sixth volume includes the beloved K488 in A major, as well as one of the first-fruits of Mozart's move to Vienna in the 1780s, the concerto K482 in E flat major (a period of the composer's life which Leif Ove Andsnes has also been focusing on, and discussed in an interview last year).

This year Manchester's acclaimed chamber orchestra the Manchester Camerata turns 50, and continues to settle into its new home, a converted monastery into which it moved last year. Among the anniversary celebrations, the Camerata's principal conductor Gábor Takács-Nagy has found time to continue his critically-hailed series of Mozart piano concerto recordings with Jean-Efflam Bavouzet; this sixth volume includes the beloved K488 in A major, as well as one of the first-fruits of Mozart's move to Vienna in the 1780s, the concerto K482 in E flat major (a period of the composer's life which Leif Ove Andsnes has also been focusing on, and discussed in an interview last year).

I was fortunate enough to catch both Gábor and Jean-Efflam to talk about this album, the factors that came together to shape the music, and the past and future of the Manchester Camerata and their own musical friendship.

This album forms part of the Manchester Camerata’s 50th anniversary year – can you tell us a bit about how the orchestra was formed and what sets it apart from other orchestras?

Gábor Takács-Nagy: It was founded fifty years ago; in the beginning it was primarily an ensemble of friends and teachers who came together to play beautiful chamber repertoire. It wasn't an amateur orchestra, but it didn't start out as the kind of ensemble that performs on the international stage. They were very good musicians – teachers, members of other orchestras, freelancers – and they were performing this chamber music of Haydn, Mozart, even going back to the Baroque.

Over time the orchestra progressed in both artistic and financial terms, and began to work with the highest calibre of conductors and soloists. When I came into the picture in 2010-11, when Douglas Boyd the previous Artistic Director was looking to take on other challenges in his life, I was chosen to take over. I've been here for eleven years; I try to do my best, but I'm also always learning.

I was originally a violinist myself, and I had some great teachers in Budapest. Douglas, on the other hand, is an oboe player – one of the best in the world – and maybe they were looking for someone who would take on that inheritance but focus more on the strings. After all, if you imagine an orchestra, the first thing you hear in your mind is the sound of the strings – though of course the wind section is very important. So it could be a factor that I'd been a string player. I could communicate to the players those things I'd learned myself, about bowing and sound quality and so on.

I think we have grown together as musicians and they like what I'm doing. Of course I have my weaknesses, as we all do, and I've tried to improve on those too. There are also two programmes that the Manchester Camerata does that I'd like to talk about – in particular the Haçienda Classical project and the Music and Dementia project. Since taking over as Artistic Director I've very much loved the open minds of the orchestral players. They're very innovative and looking towards new generations and new ways to reach the public. Our public is getting more and more conservative and older in the classical world, so it's a big mission to touch as many people's souls as possible.

One of the success stories has been the Haçienda project, working with the Haçienda nightclub and a DJ to reach different audiences, but even important has been the Dementia programme – healing people with music. Music is a kind of spiritual medicine, and I'm very proud and happy that we've been able to work with many people who are affected by dementia. In our new building we have people coming in every week, talking to the musicians, playing and singing; we also go into communities around the Manchester area. The musicians are doctors, in a sense; if the soul is happier and healthier then the body benefits too. We've been doing it for a number of years now – I can't remember exactly when it started, but three or four years at least. The orchestral musicians' participation in these sessions seems to bring them even closer together then they would otherwise be, and I realise more and more that our players are great people as well as just great musicians.

Just last year, the Camerata moved into the restored Gorton Monastery – a move reminiscent of the LSO adopting St Luke’s as its home in 2003. What led to this decision and what impact do you hope it will have?

G T-N: The orchestra's home had been in the Royal Northern College of Music in Manchester, but everyone shared a desire for us to have a new location which was just our own – like buying your own house rather than renting an apartment. When they went to this monastery, they realised it's not just beautiful from the outside but there's a very special spiritual atmosphere inside. There are also brilliant rooms for modern offices, of course, but the whole place has a soul. All of my friends who work with the Manchester Camerata say the same thing: Everybody fell in love with it.

Acoustically it's a little different to a concert hall – a little bit more boomy – and of course it wasn't built by professional expert acousticians. But on the other hand, it feels like you're a different person when you go in.

Turning to this particular recording: K488 in A major is arguably the most popular of all Mozart’s piano concertos. What do you think has endeared it so strongly to audiences over the years?

Jean-Efflam Bavouzet: Strangely enough, it's probably the least innovative of all his concertos. In terms of its structure, it's one of the only times when Mozart was following a very "by the book" procedure for how to write a concerto. There is absolutely not one single thing about it structurally that's unusual. It's almost the most banal and least interesting one, from the architectural point of view. What makes it so perfect is the beauty of the themes. It's perfect Classical proportions; the beauty of the themes and the different characters of the three movements. The first movement deals with two rather contrasting themes of incredible beauty; the second is the only piece Mozart ever wrote in F# minor, which is absolutely heartbreaking from beginning to end; and the last movement pushes the boundaries of how much joy and exuberance can be expressed musically. So it's not innovative in the way that it's written, but every movement is really taken to an extreme.

What is very interesting, though, is to compare it with K482, which is radically innovative in many, many ways - just thinking of the second movement, which is a total hybrid form between regular ABA form and a variation form; it's totally bizarre. The first movement has a huge number of themes, none of which are really great in the same way – they're very harmonically simple and perfectly good, but there are so many of them! It's as if, in one concerto, Mozart used a few themes of absolutely first rank, and in the other, there are not so many great ones but there are more overall.

They're very different approaches. But as for why K488 is so well-loved – this is an interesting thing that you encounter when you go through all of them. Sometimes you find a piece that you totally fall in love with and you wonder why it's not played more. When you have a masterpiece like K488, I think we just fall back on it.

Its haunting slow movement is unusual in both its tempo marking – an Adagio that Mozart generally eschewed in his concertos – and in its key of F# minor. Do we know anything about why Mozart took such a different approach in this concerto?

J-E B: The tempo isn't that unusual, but the difference between that and Andante is certainly important. As for why he used that key... well, let's call him up on the phone! Mozart? Hello? No, we can't know for sure because we can't ask him.

G T-N: There's an interesting thing that Tchaikovsky writes on this subject – another huge genius – and he says that whenever a melody occurs to him, immediately it has the associated key. I think that's why they are geniuses – I don't think Mozart was trying it out in different keys first to see which worked best, it came straight to him in F# minor. But I am not Mozart.

J-E B: There are also some examples in Haydn sonatas where a movement is in F minor and then followed by exactly the same in E minor – to give it a different character.

The sleeve notes for this album comment on the Masonic influences on Mozart’s music from the mid-1780s onward. How much similarity do you hear between the concerto K482 and Mozart’s more explicitly Masonic-inspired works, such as the Funeral Music and the Magic Flute?

J-E B: For me – I don't know about you, Gábor – this would be easier to answer if I was part of the Masonic community myself!

G T-N: I'm not an expert in this but what I do know is that in his pieces he's using some rhythms that are particularly associated with Masonic rituals – a particular dotted rhythm.

J-E B: I actually don't agree with that at all.

G T-N: No, not everyone does – it's really only a theory. There's another theory people have about this Masonic connection – I remember Iván Fischer, the brilliant Hungarian conductor, warning me "Gábor, it's total rubbish", and I certainly don't believe it myself – but an excellent musicologist put forward the idea that Mozart was poisoned because in Die Zauberflöte he put too many Masonic secrets – numerical secrets, hints of this and that – into the music.

J-E B: The reason I don't believe that that dotted rhythm is connected with Freemasonry is that it's used so widely. In Haydn, in Joseph Woelfl – to me it just seems to be the rhythm that was in fashion at the time. Mozart is by no means the only one using it. Just like with the bossa nova rhythm – so many great pieces were written based on that rhythm. Funnily enough, though, it's a rhythm that Beethoven never used.

G T-N: If we were to ask Mozart this question – “how much is there a Masonic element to these pieces?” – I think there's a good chance he would just shrug and say "no idea." Because it's well known that Bartók did this. Someone analysed his fifth string quartet in his presence, and this brilliant musicologist was drawing out all these points about the Golden Ratio and other things, and at the end after an hour he asked him "Mr Bartók, what do you think?" and he just said "It's possible. I don't know."

Having now recorded over a dozen of Mozart’s piano concertos, are you intending to make this series into a complete cycle? And do you know what your next project might be after doing so?

J-E B: We definitely intend to complete the cycle!

G T-N: My friend Jean-Efflam is one of the most successful recording artists and stage artists, so I'm sure he will have many more projects and I hope our paths will cross many more times.

J-E B: What could we do do? I was thinking Bach?

G T-N: Yes, Bach – because Jean-Efflam has already recorded everything else! Beethoven, Haydn... but we will find something.

Jean-Efflam Bavouzet (piano), Manchester Camerata, Gábor Takács-Nagy

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC