Interview,

Tessa Uys and Ben Schoeman on Beethoven and Scharwenka

Beethoven's symphonies exist in a number of arrangements and transcriptions for forces other than the orchestra, including several for the piano. These largely date from the era before recording technology was developed, when live performance in the home was thus the only way to reproduce music on-demand. Among the various versions is a complete set of arrangements for piano duet by the pianist and composer Xaver Scharwenka, who is an interestingly Janus-like figure – born well before commercial recordings even existed (surely contributing in part to his motivation for transcribing the symphonies), but living long enough to make some of his own for Columbia Records in the early twentieth century.

Beethoven's symphonies exist in a number of arrangements and transcriptions for forces other than the orchestra, including several for the piano. These largely date from the era before recording technology was developed, when live performance in the home was thus the only way to reproduce music on-demand. Among the various versions is a complete set of arrangements for piano duet by the pianist and composer Xaver Scharwenka, who is an interestingly Janus-like figure – born well before commercial recordings even existed (surely contributing in part to his motivation for transcribing the symphonies), but living long enough to make some of his own for Columbia Records in the early twentieth century.

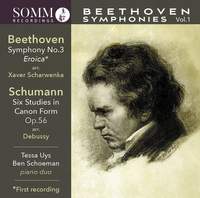

South African piano duo Tessa Uys and Ben Schoeman are now embarking on a complete set of recordings of Scharwenka's Beethoven transcriptions for Somm Records; the initial volume pairs the immortal Eroica with Debussy's transcription of Schumann's pedal-piano studies. I spoke to both Uys and Schoeman about what makes this version so unique, and how the role played by arrangements of this kind both has and hasn't changed over the centuries.

By the time Scharwenka published his arrangements in the early 1900s, the piano was physically capable of more than it had been when Czerny made the first duet versions of Beethoven’s symphonies in the 1830s. How much use do you find Scharwenka makes of these design improvements?

Carl Czerny was active earlier in the 19th Century and the piano he used did not possess a cast-iron frame which enabled the later instruments (from the 1840s onward) to resonate in larger concert halls. Czerny may have been aware of other significant developments during his lifetime, such as the invention of double-escapement (Érard) and the replacement of leather or cotton with felt on the hammers. His own musical contributions are, however, founded more on the principles of finger dexterity than experimentation with the instrument. Scharwenka had greater access to new music by composers such as Chopin, Schumann and Liszt, which required a more orchestral timbral approach to piano playing.

His own piano compositions also reflect this increased palette of sonorities, but in his Beethoven symphony transcriptions he employs the full gamut of sounds and colours that the piano could produce. He did not only attempt to bring justice to Beethoven’s intricate orchestral lines and textures, but he evidently wanted to imitate the grand soundscapes of a symphony orchestra. This indicates to us that his raison d’être in transcribing these symphonies was, not merely to bring this music into the home, but also to produce substantial concert works. Franz Schubert did the same with his vast oeuvre of piano duet music several years earlier – he may thus be a better example to cite in this instance than Czerny. In addition, as many manufacturers developed the piano in terms of range and power and in competition with one another, an instrument was produced that could be used almost orchestrally.

These arrangements are for one piano, primarily for the simple reason that most potential customers would not have owned two. How much difference is there in your experience between duets for two players at two pianos, and arrangements like these for two players at the same instrument?

Our previous answer supersedes this in a way, as we already indicate our suspicion that Scharwenka intended these transcriptions not to be mere arrangements for home use (such as other authors did – Hugo Ulrich, Otto Singer, Richard Kleinmichel, Louis Köhler and others). The Scharwenka versions of course have pedagogical significance when it comes to piano duet playing – he challenges both players to the utmost in terms of pedalling choices, fingering that would avoid clashes between the players, adjustment of the hands and seating positions, as well as articulation choices that would lead to greater clarity and colouristic variety. What he does, in our opinion, is that he amalgamates pianistic and musical education with instrumental virtuosity, and he thereby places these achievements within the realm of the concert hall and not merely the home.

We have also performed several works written for two pianos and these pose a different set of challenges and allow for the exploration of other sonorities. However, we do enjoy the process of creating orchestral colours within the more intimate medium of four hands playing at one keyboard. In this album with the duet work of Beethoven/Scharwenka and the two-piano work of Schumann/Debussy, we thus engage with two separate entities or forms of chamber music, which require a variety of technical and timbral approaches.

How much do you think it’s the case that the rise of the recording industry drove “household” arrangements like this to extinction, by making it possible to reproduce the orchestral sound in the home rather than approximate it at the keyboard?

The rise of the recording industry has not driven “household” arrangements like this to extinction – far from it. There are very many amateur and professional pianists as well as piano students, who derive enormous satisfaction from performing duets on one piano, especially Beethoven Symphonies. It takes a great deal more skill, co-ordination, knowledge of dynamics, tempi and balance than one imagines and those who essay it at home tell us they consider it as quite a challenge as well as enormous fun. The Symphonies in the Scharwenka Edition have been crying out for recording a long time now and it is all the more fun for these enthusiasts to know how closely Scharwenka has stayed to Beethoven’s original classical ideal.

In an article in the American Music Teacher of 2007, Arganbright and Weekley claim that four-hand piano duet playing is an ideal medium for modern-day music education and that the repertoire in this genre deserves equal attention to that of solo piano music. Transcriptions such as those of Scharwenka have been neglected over the past century, partly because they have gone out of print. They present apprentice and concert pianists with the challenge of coming closer to the magnitude of Beethoven’s orchestral works and we see it as our task to prevent these transcriptions from becoming extinct. We are fortunate that Tessa discovered the Universal Edition of the nine Beethoven symphonies transcribed by Scharwenka amongst her mother’s (Helga Bassel) collection. Bassel, herself a concert pianist, studied with Leonid Kreutzer, a contemporary of Scharwenka in Berlin. We therefore feel that our project reflects not only a historic, but also a personal connection with these works.

Scharwenka lived at the dawn of commercial recording, making recordings for Columbia in the 1910s as well as piano rolls. Do you think he conceived his Beethoven arrangements as pieces that would one day be recorded in their own right, or as functional and akin to recordings – merely the best method to hand for disseminating the music?

Having listened to Scharwenka’s piano rolls, we were struck by his technical brilliance and expressive playing. This inspired us on our journey with his Beethoven transcriptions. Although we can only speculate as to why he published these, we would like to believe that he would have been pleased with the sonority of modern day recording and the colouristic possibilities of the instruments on which we play his music.

Clearly Scharwenka didn’t conceive his arrangements in terms of future recording any more than Liszt, Chopin or Paderewski but we believe they would all be overjoyed that this recording, showing the amazing qualities of the piano as a polyphonic instrument, makes it possible for audiences and pianists the world over to hear and perform these symphonies in their own homes as well as in the concert hall. In our view the Scharwenka edition is the one edition which comes closest to Beethoven’s orchestra.

Schumann’s Studies in Canonical Form were originally written for the pedal piano – a piano with a pedalboard comparable to that of the organ. Why do you think this instrument never really caught on?

Mozart had an independent pedal piano made for him in 1785, the extended bass range of which is said to be reflected in the autograph of his D minor Piano Concerto, K. 466, composed in that year. He is also reported to have used the instrument in public improvisations. In the 19th century, Schumann and Mendelssohn played a significant role in the revival of earlier musical practices. The contrapuntal techniques of Bach and the pedal piano practices of Mozart thus kindled Schumann’s academic interest. He constantly embraced the new, but held on to the past, with Bach always being central. Schumann even wrote as a reminder to musicians: “Make Bach your constant study”. His Canonic Studies for pedal piano, Op. 56 reflect this combination of the old and the new – Bach-like counterpoint coupled with rich Romantic phrases and harmonies. Like the arpeggione (essentially a bowed guitar) which fell out of circulation but nonetheless inspired great works such as Schubert’s Sonata in A minor, the pedal piano also fell into oblivion, probably due to its mechanical and logistical complexity. It nonetheless proved to be a vehicle for Schumann’s profound musical expression which crystallised in his Op. 56. Virtuoso pianists like Clara Schumann and Franz Liszt, as well as those who followed in their footsteps, believed it possible that all the pianistic challenges and sonorities could be produced in the bass and treble registers of the single piano keyboard. They also had the technique to sustain several voices so that they did not need an extra set of pedals for a bass line. After Schumann’s lifetime, piano building improved to such an extent that there simply was no need for that added bass resonance of the pedal piano.

In a crude arrangement of pedal-piano music, presumably the lower part could simply replicate the erstwhile pedal part. Clearly this isn’t the case here – how does Debussy distribute the original three staves’ worth of material between the four available to a piano duo?

Debussy simply shifted the left-hand part of Schumann’s pedal piano work to the right hand of the second piano part in his two-piano arrangement of it. This in essence makes it technically easier to perform the music, as the counterpoint is distributed between the two pianists. In another way, it presents new challenges concerning sonority, balance, and ensemble-playing. The two players must be closely attuned to each other to achieve contrapuntal precision and homogenous sonority. It could be asserted that Debussy drew inspiration from Schumann’s Canonic Studies, when looking at the thematic material in the opening movement (Doctor Gradus ad Parnassum) from the Children’s Corner Suite (1908).

Like any other chamber configuration, a sense of ensemble must be critical for you as a duo. How often do you rehearse together as a unit, rather than individually?

During our countless rehearsals of these Beethoven/Scharwenka symphonies and two-piano works, we understood the necessity of mastering certain technical difficulties individually, but we also realised that it would be even more important to spend time working together as a duo to achieve what we envisage and to bring justice to this great music. Having performed these symphonies in over forty concerts, we have lived with them and spent many hours, weeks, and months on our preparation. Call it a labour of love – nobody has counted the hours involved.

Tessa Uys, Ben Schoeman (piano duo)

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC