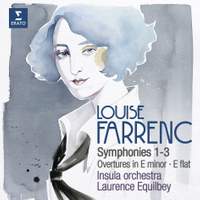

Recording of the Week,

Farrenc from the Insula Orchestra and Laurence Equilbey

Today’s Recording of the Week sees the Insula Orchestra under Laurence Equilbey begin a planned complete cycle of Louise Farrenc’s symphonic works with her first and third symphonies. Farrenc – a rough contemporary of Clara Schumann – was something of a flagbearer for the symphony within French music, at a time when this genre was seen as innately German and at odds with French sensibilities. She stands almost alone as an example of nineteenth-century French symphonists drawing heavily primarily on German traditions, and in a sense marks the end of an era – the national humiliation of the Franco-Prussian War shortly before her death would lead to a conscious effort to distance French music from German influences.

The Symphony No. 1, from 1842, has a lyrical opening, prominently featuring clarinettist François Gillardot, punctuated by dramatic outbursts before eventually revealing a fast-flowing theme that could almost have inspired the first movement of Saint-Saëns’s Symphony No. 3, composed in 1886. There are echoes of Schubert and of Farrenc’s younger contemporary Brahms, especially in her penchant for playing with expectations about stressed beats, something Brahms would later explore in his own symphonies. Her finely-constructed wind writing frequently treats the section as a quasi-concertante group set against the ripieno of the full orchestra – an approach apparent throughout both works.

The Symphony No. 1, from 1842, has a lyrical opening, prominently featuring clarinettist François Gillardot, punctuated by dramatic outbursts before eventually revealing a fast-flowing theme that could almost have inspired the first movement of Saint-Saëns’s Symphony No. 3, composed in 1886. There are echoes of Schubert and of Farrenc’s younger contemporary Brahms, especially in her penchant for playing with expectations about stressed beats, something Brahms would later explore in his own symphonies. Her finely-constructed wind writing frequently treats the section as a quasi-concertante group set against the ripieno of the full orchestra – an approach apparent throughout both works.

The Finale opens in a turbulent mood that it never truly escapes. While the earlier movements sometimes call to mind Beethoven’s Fifth, and an early moment of sunlit E flat major in the Finale hints at a comparable trajectory here, the similarities are deceptive. Farrenc provides no blaze of revolutionary triumph; the struggle between light and dark resists resolution and the closing minor cadence evokes a kind of grim determination.

The Symphony No. 3, from 1847, is introduced by a snatch of what I might now call distinctively “Farrencian” wind ensemble writing before the main Allegro. Rather than coming straight to life as in the Symphony No. 1, however, this new material stumbles to its feet, with hesitant, disjointed fragments only gradually assembling into a confident tutti. More rhythmic playfulness is on display, with every hemiola and displacement further suggesting an influence on the late-flowering Brahms.

Those appreciative of the aforementioned chamber-style wind writing will be pleased to hear that there is plenty more here, and the players clearly relish responding to it. Favouring the wind so heavily might be expected of a wind player – but Farrenc was a pianist, living in a time when the opportunity to learn orchestral instruments was largely restricted to men. Perhaps her flautist husband lobbied her, or her pioneering research into early music inspired her to reimagine the wind section as a contemporary “consort”; but whatever the reason, it’s a delight to hear woodwind textures used so generously.

The Adagio cantabile – a masterclass in elegant lyricism that is definitely my favourite movement on the album – opens with more such material; a beautiful cantilena for clarinet accompanied by rich low woodwind. Lest one think that the wind have all the fun, though, the Scherzo’s rushing semiquavers and trills put the strings through their paces – it’s credit to the players’ agility that the touch remains light, and Equilbey is clearly keen to keep the pace up, with even the calmer Trio still firmly one-in-a-bar.

The Finale has a tragic quality, again torn between agitated and more positive material; indeed both Finales seem more hotly-contested than some other symphonic conclusions of this period. No. 3 has perhaps more Sturm about it than No. 1, with sudden interjections recalling Beethoven’s pastoral thunderbolts and showcasing Equilbey’s hard-edged period timpani sound.

Among the reactions of their male contemporaries to historical female composers, one invariably finds comments that in succeeding they must have captured some essential musical “maleness”. What Farrenc represents here, though, is rather different: a Frenchwoman embracing musical German-ness. These works sit squarely within the German symphonic tradition, and it’s fascinating to consider them against the political upheavals that would shortly disrupt that lineage and forever alter the face of French orchestral music. I’m very much looking forward to the other volumes in the series – another symphony, two concert overtures and two sets of concertante variations for piano and orchestra await.

Insula Orchestra, Laurence Equilbey

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC