Interview,

Peter Cigleris on British Clarinet Concertos

Rediscovered brings back to light four clarinet concertos written by British composers in the first part of the twentieth century: Susan Spain-Dunk, Rudolph Dolmetsch, Elizabeth Maconchy, and Peter Wishart. It's an engrossing dive into one part of an evidently vast treasure-trove of forgotten works from this period, and clearly also something of a passion-project for the soloist, Peter Cigleris. I spoke to Peter about this album and the way these works have come full circle from popularity, via obscurity, back to a long-overdue return to the repertoire,

Rediscovered brings back to light four clarinet concertos written by British composers in the first part of the twentieth century: Susan Spain-Dunk, Rudolph Dolmetsch, Elizabeth Maconchy, and Peter Wishart. It's an engrossing dive into one part of an evidently vast treasure-trove of forgotten works from this period, and clearly also something of a passion-project for the soloist, Peter Cigleris. I spoke to Peter about this album and the way these works have come full circle from popularity, via obscurity, back to a long-overdue return to the repertoire,

One might say that while to lose one concerto is a tragedy, to lose at least four, as with the works recorded here, is more like carelessness. These aren’t ancient pieces lost to the mists of time – all were composed within living memory. So how did they become lost, in need of rediscovery?

That’s an interesting question and it’s very hard to say exactly why such works get lost in the mists of time. These works were composed either side of the Second World War, which would have had an impact, and the quickly changing tastes after the War to rebuild something new from the ground up.

The Dolmetsch Concerto was never heard as he died on the SS Ceramic in 1942 while on active service traveling across the Atlantic to take up a military music post - so the War clearly impacted his works, and no-one was interested in so much as looking at the manuscripts after the War, even with the support of Arthur Bliss and Edmund Rubbra.

Susan Spain-Dunk was sidelined like many after the War. Her Poem Cantilena was a popular work and was performed in the Queens Hall and broadcast by the BBC. But in the late 40s and 50s she would have been considered too post-Romantic, and the attitude was that Modernism was better. Like with Elizabeth Maconchy, Susan likely suffered from the fact that she was a woman, and as such it was easy for the decision-makers at the time to pass them by.

Maconchy’s Concertino was in the psyche partly because of Frederick Thurston and later his wife Thea King. Peter Wishart, on the other hand, forgot he ever wrote a work for clarinet: it only came to light in the years after his death having been found tucked away with other paperwork.

Naturally, you’ve focused on clarinet concertos here – but how much other music of this period do you think has suffered the same fate, and is still out there waiting for a champion to restore it to the repertoire?

Quite simply, there is a lot: it ranges from duos and trios with piano and in some cases another instrument like viola or cello, string quartet, wind quintet right up to concertante works, by both male and female composers that stretch back to around the 1870s. So much music, so little time...

Between these four concertos, the Stanford that you’ve also revived and later works by Arnold, Cooke and Finzi among others, it seems as if Britain’s early twentieth century was a particularly rich time for clarinet writing. Do you think that’s the case?

I do think that's the case because thanks to Henry Lazarus [1815-95], who could be considered the founder of the British Clarinet School, the clarinet was put on the map in the latter part of the nineteenth century. His playing and teaching inspired contemporary composers, and his students later did the same thing. Lazarus helped elevate the clarinet to the level of appreciation that saw composers like Brahms giving full musical expression to it. One could in fact argue that the London premiere of the Brahms Clarinet Quintet was the catalyst. Stanford was at that premiere, and then went back to his class of students at the Royal College of Music full of enthusiasm and asked them all to compose a quintet. The winner of that ‘in-house’ competition was Samuel Coleridge-Taylor.

As we look at the first half of the twentieth century, we see many clarinettists coming to the fore premiering works, such as Charles Draper and the Stanford Concerto. Later on, we see the emergence of players such as Reginald Kell and Frederick Thurston who had direct involvement with the works on this new album.

Of the composers featured on this album, Susan Spain-Dunk is probably the least well-known, yet she seems to have been fairly acclaimed in her own time. Why do you think she faded into obscurity in the ensuing decades?

Susan was a rising star for sure in first half of the twentieth century. She graduated from the Royal Academy of Music having won the Charles Mortimer Composition Prize, and set out forging a career. She played violin with various orchestras including the Royal Opera House, but it was when she won the illustrious Cobbett International Competition that her composing took off. Several chamber works followed, and then in 1925 Henry Wood selected her Suite for Strings for performance at the Promenade Concerts. This gave Susan her Proms conducting debut, and she is still the only other woman to conduct her own music at the Proms after Ethyl Smyth. This was a success and resulted in further engagements conducting her music at the Proms; Henry Wood in fact commissioned Susan to write a work for the following year's Proms on the back of that debut concert.

It was in the 1930s that Susan was chosen to have some works broadcast by the BBC; these were the Poem Cantilena recorded here and the tone poem Stonehenge. After the War it was incredibly hard for Susan to get any kind of recognition, which must have been extremely frustrating for her after her Proms concerts and BBC broadcasts. The sad truth is that there was a big lurch away from the old and an embracing of the new. Modernism was the way forward now and Serialism was preferred. This was also embraced by the Third Programme [precursor to BBC Radio 3] when it came on air in 1946. Susan wrote many letters to the BBC after the War asking if new compositions could be considered while reminding them of her success in the 1930s, though sadly all replies were the same: “We cannot consider this at this time”.

Susan composed with a post-Romantic style with lush rich textures and harmony and, like many others such as Bax, was considered outdated. The mood seems to have changed back, and so it’s probably the right time to rediscover Susan and her fellow colleagues and the rich culture of music that has been unjustly forgotten.

The Dolmetsch concerto’s neo-Baroque leanings are remarkable – how much do you think this approach is due to Rudolph’s heritage and upbringing within the influential Dolmetsch clan of early-music revivalists?

Rudolph’s background undoubtedly had a huge impact. He was fully immersed in the early-music revival and became the country's foremost harpsichordist. In many ways you could argue that the Dolmetsch family heavily influenced the ‘Nationalist’ composers in their search for folk tunes and structures to imitate in their own compositions. More study will need to be done on Rudolph’s other works to see if the neo-Baroque style of the Concerto for Clarinet and Harp is prevalent, as this recording is the only recording of a work by Rudolph Dolmetsch.

Two particular performers – Frederick Thurston and Reginald Kell – seem to have been instrumental in the genesis of all four works. Is there any evidence that they had direct influence on the composition, perhaps by collaborating with the composers?

Regarding the Spain-Dunk, Dolmetsch and Wishart, unfortunately there is not a lot to go on. Through connecting of dots and threads we can say that Thurston and Kell as players are connected to these works but it's perhaps speculative to suggest that either player had a hand in the genesis of any of them. What I do know is that Kell gave the very first performance of Poem Cantilena, albeit with piano, at a private event. I don’t think it would be a fair stretch to suggest that he might have made suggestions to Susan on the solo writing. By the time Thurston came to broadcast the work the part was established.

It's quite possible that Dolmetsch had players in mind, as he had made a rehearsal version of his concerto for the soloists and two pianos, but sadly the documentation on the genesis is virtually non-existent. With Wishart’s Serenata Concertante there could have been some intention to collaborate, or it could have been the case that he knew who would be playing the work without knowing the player personally.

Maconchy’s Concertino, however, did involve collaboration between Elizabeth and Frederick Thurston: there are letters arranging times for ‘Jack’ and Thea, at the piano, to play through the work leading up to the first performance in Copenhagen. It’s very possible that Thurston would have made suggestions on the solo writing.

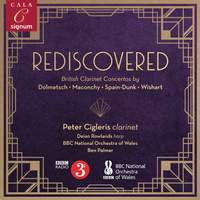

Rediscovered

British Clarinet Concertos by Susan Spain-Dunk, Rudolph Dolmetsch, Elizabeth Maconchy, and Peter Wishart

Peter Cigleris (clarinet), Deian Rowlands (harp), BBC National Orchestra of Wales, Ben Palmer

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC