Favourites,

Shelf Discovery: Yehudi Menuhin

“As a boy I hoped - I had the childish idea - that if I played the Chaconne of Bach beautifully enough - but it would have to be very, very beautiful - I could bring peace.”

“As a boy I hoped - I had the childish idea - that if I played the Chaconne of Bach beautifully enough - but it would have to be very, very beautiful - I could bring peace.”

Though this statement by the violinist Yehudi Menuhin in 1995 might seem to be one of childish naiveté, it not only gives an insight into the personality of one the twentieth century’s most important musicians but also reveals a strong element of his artistic and moral credo that sustained an entire career.

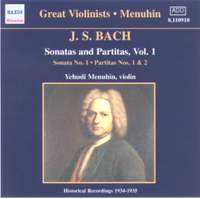

He tried multiple times on record to play the Bach Chaconne beautifully enough, but I think he actually came closest with his first attempt in 1935 (a recording of the complete Sonatas and Partitas which stands alongside Edwin Fischer's Well-Tempered Clavier and Pablo Casals's Cello Suites as the first recordings of music that was previously viewed as primarily pedagogic). This was perhaps less due to Menuhin losing his faith in his ability to do so as he got older, but more prosaically to the much-discussed problems with technique in his later years, possibly caused by the unusual way he learnt the violin - there is a famous anecdote that backstage after a flawless concerto performance he was asked to play a scale and simply couldn't.

You don't need to be a historian to know that the decade that following Menuhin's initial recording of the Chaconne was not one in which the world was blessed with peace, and though Menuhin's commitment to the pacifist cause evolved and matured throughout his post-war career three central tenets remained constant: reconciliation, the promotion of cultural understanding, and education.

After giving concerts throughout the war to support the Allied effort he then surprised the world by performing with Wilhelm Fürtwangler in 1948, and this collaboration was preserved with recordings of the Beethoven, Brahms and most interestingly Mendelssohn concerti. The Mendelssohn concerto was of course banned in Germany until 1945 and there is an almost frenetic intensity here, far removed from the 'gemütlich' quality so often associated with this work, especially in the opening Allegro. Central to Menuhin's repertoire throughout his career was the Beethoven concerto, and having sampled both his versions with Fürtwangler, I'm inclined to agree with the general critical consensus that the earlier performance (Lucerne, 1947) is preferable to the later, from 1953 with the Philharmonia. Although the first movements are largely identical in tempo and phrasing, there is a greater depth of intensity in ’47 - especially in the rapt slow movement, which Menuhin described as not only one the most sublime moments in all music, but “the best in all of us that we call humanity”.

After giving concerts throughout the war to support the Allied effort he then surprised the world by performing with Wilhelm Fürtwangler in 1948, and this collaboration was preserved with recordings of the Beethoven, Brahms and most interestingly Mendelssohn concerti. The Mendelssohn concerto was of course banned in Germany until 1945 and there is an almost frenetic intensity here, far removed from the 'gemütlich' quality so often associated with this work, especially in the opening Allegro. Central to Menuhin's repertoire throughout his career was the Beethoven concerto, and having sampled both his versions with Fürtwangler, I'm inclined to agree with the general critical consensus that the earlier performance (Lucerne, 1947) is preferable to the later, from 1953 with the Philharmonia. Although the first movements are largely identical in tempo and phrasing, there is a greater depth of intensity in ’47 - especially in the rapt slow movement, which Menuhin described as not only one the most sublime moments in all music, but “the best in all of us that we call humanity”.

Facing increasing difficulty with his technique in the late 40s and early 50s, Menuhin discovered and helped popularise Yoga in the West, but of course Yoga would not be his greatest contribution to improving relations and cultural understanding between the West and the Indian subcontinent. Years before The Beatles, in 1952 legendary sitar player Ravi Shankar and Yehudi Menuhin met, although Menuhin admitted that it took fifteen years before he found the courage to actually play with him; the resulting collaboration (which Menuhin would treasure throughout his life) undoubtedly contributed to a surge in interest in Indian classical music, and Indian culture more generally around the world. The intoxicating and exhilarating ‘Raga Piloo’ has probably proven to be the most iconic track from the album, and was performed by Menuhin and Shankar at the United Nations in 1967; it’s since been performed by Daniel Hope and the ceaselessly inquisitive Patricia Kopatchinskaja, the latter with Shankar's daughter Anoushka.

Facing increasing difficulty with his technique in the late 40s and early 50s, Menuhin discovered and helped popularise Yoga in the West, but of course Yoga would not be his greatest contribution to improving relations and cultural understanding between the West and the Indian subcontinent. Years before The Beatles, in 1952 legendary sitar player Ravi Shankar and Yehudi Menuhin met, although Menuhin admitted that it took fifteen years before he found the courage to actually play with him; the resulting collaboration (which Menuhin would treasure throughout his life) undoubtedly contributed to a surge in interest in Indian classical music, and Indian culture more generally around the world. The intoxicating and exhilarating ‘Raga Piloo’ has probably proven to be the most iconic track from the album, and was performed by Menuhin and Shankar at the United Nations in 1967; it’s since been performed by Daniel Hope and the ceaselessly inquisitive Patricia Kopatchinskaja, the latter with Shankar's daughter Anoushka.

Although Menuhin was one of the most recorded violinists of the twentieth century, his most enduring legacy could well prove to be his educational work, although sadly his eight-part 1979 TV series The Music of Man has been largely lost to the mists of time. Offering a much more lasting legacy is the Yehudi Menuhin School in England, where fees are based solely on parents’ ability to pay: clearly the school not only nurtures great musicianship, but also fosters the belief that music can be harnessed as a force for social change. Nicola Benedetti, a Menuhin School alumna whose Benedetti Foundation Presto Music was proud to support last year, proves that this spirit is alive over twenty years after Menuhin's death.

In that speech in 1995, four years before his death, Menuhin concluded by saying “Well, I have not succeeded [in bringing peace], but I am still concerned with harmony and with the idea of dynamic balance, of reciprocity of equilibrium, of complementarity.” It is those very ideas which can create a culture without which peace is impossible: equipped with only a piece of carved wood (either a bow & violin or later in his career a baton) and a simple credo, Menuhin achieved more to this end than virtually every self-professed peacemaker of the past century.

Yehudi Menuhin (violin)

Available Formats: MP3, FLAC

Yehudi Menuhin (violin)

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC

Lucerne Festival Orchestra, Wilhelm Furtwängler

Available Format: CD

Yehudi Menuhin (violin), Ravi Shankar (sitar), Alla Rakha (tabla), Kamala Chakravarti (tambura), Nodu Mullick (tambura)

Available Formats: MP3, FLAC