Interview,

Roderick Williams on the songs of Arthur Somervell

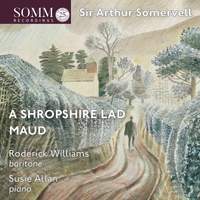

Acclaimed baritone Roderick Williams's most recent recording, on Somm Records, sees him explore Housman's evocative A Shropshire Lad poems - but not in the musical guise in which they're most often heard. Instead, Arthur Somervell's setting of the cycle is paired with his adaptation of Tennyson's Maud, in an album devoted wholly to this often overlooked composer.

Acclaimed baritone Roderick Williams's most recent recording, on Somm Records, sees him explore Housman's evocative A Shropshire Lad poems - but not in the musical guise in which they're most often heard. Instead, Arthur Somervell's setting of the cycle is paired with his adaptation of Tennyson's Maud, in an album devoted wholly to this often overlooked composer.

Roderick was kind enough to share some of his thoughts on this album with me.

You’re by no means a stranger to recording lesser-known English song, with recent albums of premiere recordings by Holst and Vaughan Williams. Where did the idea first come from to record this album of Somervell?

Susie Allan has actually recorded the Somervell before, a long time ago, with baritone Henry Wickham (husband to author Sophie Kinsella) so she has known the pieces for ages. She has been gently nudging me for years to look at them and finally I got round to it.

Compared to some other English song-cycles, Somervell’s have been relatively rarely performed, let alone recorded. Is this just a case of their Victorian idiom having fallen out of fashion since Somervell’s time?

I have a feeling that Somervell’s song-writing style, like that of Stanford and Parry (whose songs I have also recently been recording), is neither the standard Victorian parlour song nor the full flower of early twentieth century English song. It sounds to me as though all three of these composers were consciously trying to forge a new, more heavy-weight genre of song-writing after the German Lieder model. Perhaps, until now, history has judged them harshly against both their European counterparts and against the lighter, popular music that was so prevalent in Britain at the time.

Your commentary in the notes to this album sets Maud in its context as a series of excerpts from a surprisingly grim story of grief and angst, yet many of the songs themselves seem innocently melodious. Why do you think Somervell didn’t delve deeper into the dark side of the poems in his music?

I can’t really comment much on Somervell’s reason for setting the songs so lyrically, except to say that Garry Humphreys, who has been doing a lot of work and research recently around Somervell, tells me that a relative of Tennyson’s remarked to Somervell once that he had set them to music very much in the way Tennyson used to read them. So my twenty-first century interpretation of the poem may be completely at odds with Tennyson’s intentions. Who’s to say?

How much do you find “reading around” a song-cycle to set it in its literary context informs your performance of it? Should the music stand by itself even in a vacuum, or is understanding the background vital to presenting it convincingly?

It is satisfying if a piece of music can stand on its own, especially so that people hearing it for the first time can be drawn into it without feeling they should have done homework before listening. But it can also enrich one’s understanding of a piece if you can discover further layers within it, once you’ve discovered it has a specific context. There are occasions when reading around a character or a piece can fill you with amazing ideas, only for you to discover there is actually only so much room within the piece for you to explore your research. (I found this a little, for example, with the role of Eugene Onegin. Pushkin’s poem and Tchaikovsky’s treatment of it are different pieces and it wasn’t always that helpful trying to impose one on the other.). So I think it helps to read around a subject in order to increase one’s own understanding but what you do with that context can require a bit of tact.

The Housman poems are, of course, enormously popular among composers to this day; Somervell was merely the first to set them to music. What do you think it is about them that gives them such an enduring appeal to song-writers?

I have a feeling the appeal might be two-fold; firstly, Housman’s poems, especially in Shropshire Lad, tend to be short. Composers are often drawn to short, succinct poetry for songs and audiences like that too. Think of all those three-minute pop songs today! Housman’s poems are also written in deliberate basic language, which means they appear to be simple to grasp, again, like modern pop songs. And also, like some trendy, modern pop lyrics, when you really begin to think about the words, you discover a whole world of subtext beneath them, subtext that is not at all obvious. People can argue endlessly about the meaning behind the lyrics and can have their own, personal reading of the words. For a composer this is something of a gift, as it means the accompaniment can inhabit the world of subtext while the singer deals with the words at face value.

Many people will know Butterworth’s setting of A Shropshire Lad; why do you think Somervell’s earlier settings have been relatively sidelined by comparison?

My personal thought on this is that Butterworth left much more room through the simplicity and restraint of his writing to let Housman’s subtext speak. Somervell, to my mind, reads the poems more at face value and leaves much less room for manoeuvre. For what it’s worth, I sometimes feel that later settings of Housman by composers such as Moeran and Ireland, even Vaughan Williams’ On Wenlock Edge, spend relatively more time on the existential angst between the lyrics, so that it is in danger of swamping the understatement of the poetry.

You’ve recently recorded an album of Beethoven and Schubert Lieder; how much of an influence do you think that German school was on English song-composers such as Somervell?

I would like to imagine that Somervell was writing Maud with a copy of Dichterliebe sitting on his desk. There are so many similarities between the two that I cannot help thinking this was his model. A great deal of the piano writing in particular feels Schumann-esque, as does the pacing of the story sections that Somervell chose. For example, Come into the garden, Maud performs the same function as 'Das ist ein Flöten und Geigen', [Flute and violin music are playing], when an outsider listens to party/wedding music from a distance; both songs share almost ironic dance music burbling away in the piano part. Also, the idea in Shropshire Lad of referring back to the music of previous songs in order to make the set cyclic is, I’m convinced, an idea borrowed from Schumann. Elevating art song, taking it out of the pubs and the music hall and putting into chamber music recitals, was a concept most likely borrowed from Germany. We have a lot for which to thank the German Lieder tradition.

Roderick Williams (baritone), Susie Allan (piano)

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC