Interview,

Odaline de la Martinez on Ethel Smyth

The music of British composer Ethel Smyth has been enjoying something of a revival in recent years, thanks in no small part to the efforts of conductor Odaline de la Martinez, who has championed her works and those of other hitherto neglected female composers in numerous recordings.

The music of British composer Ethel Smyth has been enjoying something of a revival in recent years, thanks in no small part to the efforts of conductor Odaline de la Martinez, who has championed her works and those of other hitherto neglected female composers in numerous recordings.

De la Martinez conducts four of Smyth's orchestral songs on a new album from Somm with contralto Lucy Stevens, with Elizabeth Marcus at the piano for the remainder; I spoke to her about Smyth and about her thoughts on the evolution of attitudes towards the promotion of female composers' music.

During her own time, many male critics either praised Smyth for successfully emulating “maleness” in music or condemned her for doing so too well. Is there any evidence that Smyth tried either to be consciously “feminine” to make a statement, or conversely to adopt a musical “masculinity” (whatever those two things might be) as a route to mainstream success?

I certainly don’t think you can write “masculine music”, but back then they didn’t really know how to cope with someone like Smyth. A lot of female writers in the early twentieth century didn’t use their own names: they wrote under a pen-name or used initials, because there was a perception of what women were like, and what “male music” was like, so if anybody wrote in any style that was anywhere near that it was described as masculine. But there is no such thing!

Conversely, song-writing at this time was an area in which women composers (such as Maude Valérie White) really excelled, and as a result some men started using pen-names that were gender-neutral or implied they were women, in the hope that this would aid the acceptance of their songs. It really was an exceptional time: people knew something about women writing songs, but not major works like symphonies.

All people really knew in the area of symphonic writing was Beethoven and Brahms, and you can connect some of the thinking in Smyth’s Mass to Beethoven - not the style itself, but the thoughts behind it and even some of the keys. I suspect that she had studied Beethoven thoroughly by this point, but I think she was even more influenced by the late Romantic music that she was hearing in Germany and the UK. The movement in the Mass where the mezzo-soprano is accompanied largely by the brass, for instance, is much more Brahmsian.

Despite the steps that have been made in gender equality since the time of the suffragette movement, female composers are still often treated as a specialist category. How far do you think we are from incorporating Smyth and other women on a truly equal basis into our thinking about music?

“Flavour of the month” sums up how I look at this kind of question: while it’s fashionable, everyone is very keen to promote women and jump on the bandwagon, and then it subsides and we’re back to Square One. Throughout history there have been periods, for instance immediately after when women gained suffrage in the 1920s, when women were heavily featured: you see that in what was commissioned and performed at the Proms. But then that dissipated, and the interest in women composers – and conductors such as Ethel Leginska, born ‘Ethel Liggins’ in Hull – died out. It happened again in the late ‘60s after the big advances in women’s rights, and we’re seeing it now as we celebrate a hundred years of suffrage. I wish I were wrong about this – so many people argue with me about it! – but the historical record is very clear. It’s a sine curve that goes up and down where you see women flourishing for a period and then disappearing, and I think we’re at the top of that curve now.

Given this, I think it’s our duty to ensure that we don’t fall all the way back down each time this cycle recurs. One aspect of this concerns archiving – I don’t want to promote myself too much here, but I’m very keen to record and archive women’s work. Publishing itself isn’t always the issue: Clara Schumann and Fanny Mendelssohn’s works were published during Clara’s lifetime and in Fanny’s case after her lifetime, but a lot of it just ended up in obscure libraries and effectively disappeared. So there’s a need to create some kind of an archive so that these works are readily accessible.

The British Library is currently taking a lot of my CDs: they approached me and said they thought the work I was doing was very important, and the fact that this music is now in the library means that when someone comes looking for it they’ll be able to find it. Previously that’s been left to publishers, but publishers can go out of business or discontinue a product because nobody wants to buy it. And sometimes they have so many composers on their books that they don’t know who to promote, so they stick to the ones who are fashionable now.

In the case of Smyth, the reason for her music’s disappearance was actually very straightforward. When I first started recording her music I had a long conversation with Universal Edition about why they had lost so many of her scores, and the answer was simple: in 1939 most of her music was published by Universal Vienna rather than Universal London, and when the Nazis occupied Vienna Smyth was so angry that she withdrew all her scores and took the copyright back from Universal. She died in 1944 without having returned it, so Universal were still acting as an agent that could represent her - but if you’re trying to determine which scores you’ll prioritise then naturally that money is going to go to the ones where you hold the copyright as well.

Nowadays Smyth is within the relative mainstream – partly through my own efforts, I’d like to think. I was in New York recently and met someone who’d given the American premiere of one of her works; he greeted me with “We share a Dame!”, and it took me a while to realise that he was talking about Dame Ethel! He felt a sense of ownership from having conducted the piece, which is a great thing, because now he feels like he can programme more of her works. Let’s not be possessive about this music: if enough people have a share in her, then we stand a chance that performances will continue.

Many composers show different “personalities” through different genres; one thinks of Shostakovich’s chamber music compared with his symphonies. Is the same thing true of Smyth – do you hear a different side to her in some of these song settings than in her larger-scale works?

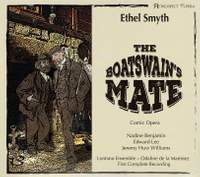

She changed style throughout her career and was very aware of trends in composition around her – that’s why she adopted the neoclassical style at one stage, for instance in Fête galante, with sections titled after Baroque dances. It’s a particularly interesting question in terms of her operas: the style of The Wreckers is very late-Romantic, whereas The Boatswain’s Mate is full of folk-song and lightness and a sense of exploration. The reason that The Boatswain’s Mate was so influenced by folk-songs was that it was written right after a period where three major things were upsetting her: firstly the death of Henry Brewster, which really broke her heart; secondly the two years that she spent as a suffragette, ending up in jail; and thirdly her feeling that the British public didn’t care about opera as they did on the Continent, or at any rate were only interested in Gilbert & Sullivan.

As for the songs, such as the four orchestral ones on this album, these were almost a parenthesis. At the turn of the century when they were written, Smyth was spending a lot of time in Paris and had befriended some Parisian composers such as Augusta Holmès (initially “Holmes”, but she added the accent upon taking French citizenship), who was writing operas including La Montagne Noire, which Smyth had gone there specifically to hear. Smyth’s connection to Paris was very significant – during her time as a suffragette she would also go there to hide from the British authorities. I would definitely say that the style is still recognisably Smyth (particularly the Ode anacréontique where her voice comes out loud and clear), but some of the earlier ones have a flavour of “I’ve been to France” about them. That’s why Debussy was so fond of them – he called them “tout à fait remarquable”, wholly remarkable.

The Three Songs dating from 1913 clearly stand out as overtly political, rallying-cries for the suffragette cause. With female suffrage now extended almost worldwide, do you view these songs as historical documents, or as something more alive?

I think it’s very narrow to view them as purely political - the only one that is overtly so is On the Road, which is definitely a suffragette song! But I agree with what Lucy Stevens argues in the sleeve notes: they’re different ways of talking about freedom. Maurice Baring was a great supporter of Smyth’s (she wrote a book about him, which I have); she simply loved his poem and I’m sure she connected what he was saying about the fact that women were enslaved, and the same is true of Possession. On the Road and Possession were both written by a suffragette, Ethel Carnie Holdsworth, and they talk about the same thing, about letting women go.

Can you tell us anything about your own relationship with Smyth’s music – when did you first come across her?

Around 1990 the Chard Festival of Women in Music asked me to form an orchestra of women musicians to showcase women composers, to be conducted by me as a woman conductor. I spoke to Sophie Fuller, who wrote The Pandora Guide to Women Composers, and she suggested I look at Smyth. Universal led me towards the Serenade in D and having found that score to be so extraordinary I started investigating her music more generally.

That whole experience made me realise that I, as a woman conductor and composer myself, was not giving fair consideration to women composers; I was thinking of them just the same as everyone else did at the time: “Oh, well, she’s just a woman composer”. Smyth’s scores and the tremendous power of them really opened my eyes, and since then I’ve devoted a lot of energy to promoting women composers. In the process I’ve recorded a lot of her work, including this album on which I’m conducting the four orchestral songs, and before that Fête galante. I was delighted that Lucy asked me to do this, as I’ve done the four songs before many times, in all kinds of places including New Zealand, where we recorded it for the radio.

Now Smyth is finally coming into the limelight and being acknowledged, and I’ve been trying to do the same thing with Elizabeth Maconchy, whose orchestral and choral works, with BBC forces, I’ve recorded with funding from the RVW Trust. When I went to try to get funding to record Smyth’s Serenade in D, I went to the RVW Trust and they sponsored the CD (meaning the money went to the record company that released it). They’ve been very supportive, but their mission is to support little-known composers of contemporary and recent music – and I think if you went back to them today and tried to get money to promote or perform Smyth or Maconchy, you wouldn’t get it because they are no longer neglected. That is an achievement!

There’s one piece of Smyth I really want to do called The Prison but just can’t find the money – so if someone reads this and can fund it I’ll be delighted! It really is a terrific piece, and one of the last things she ever wrote; I think of it as a choral symphony, about 75 minutes long. I suggested it for the Proms, but David Pickard told me it wasn’t suitable – if that piece isn’t suitable, then what is? Maybe now I’ve said this they’ll never let me do another Prom again, but I was very shocked at that response. This is a major choral and symphonic work by a great composer whose greatness is thankfully no longer a point of contention as it used to be: when I first did The Wreckers one of the singers described it as “Women’s Institute music” despite the fact that he’d never heard it before!

At the end of the day, it’s all about fighting for somebody who deserves to be fought for.

Lucy Stevens (contralto), Elizabeth Marcus (piano), Berkeley Ensemble, Odaline de la Martinez

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC

Charmian Bedford (soprano), Carolyn Dobbin (mezzo), Felix Kemp (baritone), Simon Wallfisch (baritone), Mark Milhofer (tenor), Alessandro Fisher (tenor), Dame Felicity Lott (reciter), Valerie Langfield (piano), Lontano Ensemble, Odaline de la Martinez

Available Format: CD

Sophie Langdon (violin), Richard Watkins (horn), BBC Philharmonic, Odaline de la Martinez

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC

Anne-Marie Owens (Thirza), Justin Lavender (Mark), Peter Sidhom (Pascoe), David Wilson-Johnson (Lawrence), Judith Howarth (Avis), Anthony Roden (Tallan), Brian Bannatyne-Scott (Harvey/A Man), Annemarie Sand (Jack), Huddersfield Choral Society, BBC Philharmonic Orchestra, Odaline de la Martinez

Available Format: 2 CDs

Nadine Benjamin (Mrs Waters), Edward Lee (Harry Benn), Jeremy Huw Williams (Ned Travers), Simon Wilding (Policeman), Ted Schmitz (The Man), Rebecca Louuise Dale (Mary Ann), Mark Nathan (chorus), Lontano Ensemble, Odaline de la Martinez

Available Format: 2 CDs