Interview,

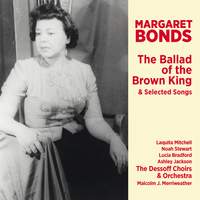

Margaret Bonds's The Ballad of the Brown King

A collection of powerfully socially-charged songs by Margaret Bonds flanks the centrepiece of this recording - the equally impactful Ballad of the Brown King, which picks up and develops a popular legend surrounding the Three Kings of the Christmas story.

A collection of powerfully socially-charged songs by Margaret Bonds flanks the centrepiece of this recording - the equally impactful Ballad of the Brown King, which picks up and develops a popular legend surrounding the Three Kings of the Christmas story.

It has become common to portray the Kings as each representing a different culture and ethnicity, with one among them very often of African descent; the poet Langston Hughes takes this tradition as the starting-point for a striking libretto meditating on the implications of a dark-skinned monarch, and the contrast with his and Bonds's own social realities as black artists in early twentieth-century America - and her instantly infectious music brings the text to vivid life.

I spoke to Malcolm J Merriweather, who conducts The Dessoff Choirs and Orchestra on this recording, and to Dr Ashley Jackson, one of the world's leading authorities on the music of Margaret Bonds and harpist on this recording, about this intriguing and unique Christmas album.

Given how different the social and cultural conditions were in 1930s America, how was The Ballad received during Bonds’s lifetime? How did it come to slip out of favour until your revival of it?

M.J.M.: Margaret Bonds wrote music on par with contemporaries like Menotti, Barber, and Schuman. One only has to look at her songs, chamber music and The Ballad of the Brown King to see that. However, like most African Americans, she faced gender and racial bias in various forms. This undoubtedly contributed to the lack of access to her music. Many of these practices stem from the Reconstruction era; but they held back Margaret Bonds and still haunt the classical music community in 2019.

A.J.: The Ballad of the Brown King was performed nationally and internationally following its premiere in 1960. The Civil Rights Movement had been gaining momentum, and Bonds knew that the work’s message of universal brotherhood would resonate strongly with the times during which it was written. This is what partly motivated her to dedicate the revised 1960 version to Martin Luther King, Jr. Unfortunately, the orchestral version was never published, and the piano/vocal arrangement has been out-of-print. This, along with the fact that there had been no professional recordings of the piece until this one, is a significant factor in why it came to “slip out of favour.” Choirs and directors simply are not aware of it and/or do not have access to the music.

Every so often, people point out that, in all probability, the “three kings” of school Nativity plays technically weren’t either monarchs or three in number – and that similarly the tradition of their being various different ethnicities is a piece of folk mythology that’s been spun over the centuries. Do you think this matters when thinking about the use Bonds makes of the image of the Brown King?

A.J.: I won’t attempt to suggest one way or another whether there were three kings of varying origins. But as you mention, it is the most common version of the nativity story, and certainly one that would resonate with many audiences. It absolutely matters when Langston Hughes writes, “Of all the Kings who came to call, one was dark like me.” Because whether or not in fact it is historically accurate, it allows black listeners to feel part of a story that in so many depictions leaves them out.

M.J.M.: I think it’s fitting if we look at this story from a historical point of view. Regardless of the racial accuracy, this narrative gives African Americans a positive image rarely portrayed in history, books, and art. A brown sovereign, travelling in majesty and splendour? It is unheard of. African Americans are not just descendants of slaves; but, we come from great Kings or Queens that ruled kingdoms with sophisticated political and economic systems on the continent of Africa.

M.J.M.: I think it’s fitting if we look at this story from a historical point of view. Regardless of the racial accuracy, this narrative gives African Americans a positive image rarely portrayed in history, books, and art. A brown sovereign, travelling in majesty and splendour? It is unheard of. African Americans are not just descendants of slaves; but, we come from great Kings or Queens that ruled kingdoms with sophisticated political and economic systems on the continent of Africa.

Contrasting with The Ballad, the other songs featured on this disc have a rather sharper social focus – above all I, too, which seems to prefigure the well-known “I am a man” placards of the civil rights protests. Would it be fair to say Bonds was engaging in overt political activism through some of her music, or was she merely expressing her own identity (or, indeed, both)?

M.J.M.: I think she is expressing both. Using the sophisticated rhetoric of Hughes, Bonds has a solid canvas to create musical colors and moods. When I sing 'Dream Variation' I feel the weight of my ancestors on my shoulders through the harmonies and textures. In Bonds, I see my aunts, grandmothers and even my own mother - strong, capable women who at one point or another were undervalued and stifled by white supremacy in America. That sense of struggle is not merely expressed but it screams to me. It is all packaged neatly in the form of an art-song.

A.J.: As a young college student at Northwestern, Bonds was drawn to the poetry of Langston Hughes because he captured so many of the complexities that she had been experiencing as a black woman, but perhaps couldn’t yet put into words. Bonds was certainly conscious of the power of art and music to speak in ways that words or direct action may not. She had grown up in Chicago during the Harlem Renaissance, and it was not uncommon for these prominent black artists to pass through her mother’s house on the South Side of the city. From them she inherited the belief that her gifts could be used for social change.

Bonds’s style is enigmatic; on listening, one hears mostly an accessible, unfussily Romantic voice with perhaps faint echoes of Barber and Copland, but it’s hard to pin down any more specific influences. Who would you say were the key figures that shaped her compositional voice – and how much did it evolve over her career?

M.J.M.: I do not necessarily hear Barber or Copland in Bonds’s idiom. What I do hear is a distinct mid-century voice that incorporates elements of neo-Classicism while also weaving in popular elements. I hear the great orchestra of Nat King Cole, especially in the treatment of the strings.

A.J.: Yes, stylistically The Ballad incorporates a lot of different styles. It’s quite fascinating, and perhaps may reflect the fact that it was first composed in 1954 and then revised in 1960. Her compositional voice seems most focused in the art songs. She was certainly influenced by Florence Price (one of her earliest composition teachers) and Harry T. Burleigh. She also deeply admired the Romantic lieder of Schubert. In The Ballad you can also hear the influence of her time spent working as a rehearsal pianist for shows in 1940s New York. She really seems to draw from a variety of sources throughout her career.

A.J.: Yes, stylistically The Ballad incorporates a lot of different styles. It’s quite fascinating, and perhaps may reflect the fact that it was first composed in 1954 and then revised in 1960. Her compositional voice seems most focused in the art songs. She was certainly influenced by Florence Price (one of her earliest composition teachers) and Harry T. Burleigh. She also deeply admired the Romantic lieder of Schubert. In The Ballad you can also hear the influence of her time spent working as a rehearsal pianist for shows in 1940s New York. She really seems to draw from a variety of sources throughout her career.

The arrangement of The Ballad recorded here, for strings, harp and orchestra, is an adaptation by Malcolm Merriweather. How was the work originally scored, and how different do you think this version is?

A.J.: The 1954 version of The Ballad was scored for mixed voices, soloists, and piano. Sometime between 1954 and 1960, Bonds decided to orchestrate the work for full orchestra. This version was never published, but was made available as a rental for a short period of time. I’ll let Malcolm continue!

M.J.M.: The original instrumentation is for full orchestra - this includes brass, woodwinds, strings (harp), and percussion. Hiring an orchestra of that size can be expensive thereby making performances of the work rare. This edition for harp, strings, and organ omits the woodwind and brass parts. Essentially those instrumental lines are absorbed into the organ part. The string parts are largely original and the harp part is enlivened to add texture. The organ functions as an orchestral instrument and registrations should blend with the other instruments while providing depth and dramatic color. All of the decisions in the edition were influenced and informed by Margaret Bonds’s idiom as analyzed in other songs and choral music.

The music of The Ballad of the Brown King seems within the grasp of the talented amateur choir; given this, and your own advocacy for Bonds’s work, do you see The Ballad becoming a fixture of Christmas musical festivities in America in years to come?

A.J.: Having a recording of The Ballad will make this work so much more accessible than it has been. It is just wonderfully written for the voice, and in the making of this recording, you can tell it is a joy to sing. The next step is have this pared-down version published and made available to the public. There is a much-needed effort towards programming works that reflect the beautiful diversity of this country, and this piece just so beautifully does that. Bonds wanted to compose a work that would bring people together, all kinds of people. I look forward to hearing this work in the years to come.

M.J.M.: Yes, you are correct! This piece is so accessible and it feels good to sing. The pacing of the piece would make a great centrepiece for any holiday program—or outside of the holidays. Let’s make this happen! Soon we will be learning of premieres in other states and countries. That would be a fitting homage to Margaret Bonds, and her dear friend, Langston Hughes.

Laquita Mitchell (soprano), Lucia Bradford (mezzo-soprano), Noah Stewart (tenor), Malcolm J. Merriweather (baritone/conductor), Ashley Jackson (harp), The Dessoff Choirs & Orchestra

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC