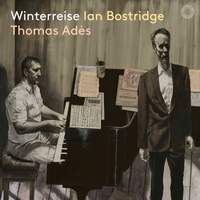

Recording of the Week,

Winterreise from Ian Bostridge and Thomas Adès

When I came back from a press-conference earlier this year with the news that Ian Bostridge was to record Schubert’s three great song-cycles for Pentatone, I met with a chorus of ‘Again?’, ‘Already?’, and ‘Why?’. It’s barely a decade since the idiosyncratic British tenor completed the trilogy on Warner Classics, where Leif Ove Andsnes accompanied him on a ‘Winter’s Journey’ of such pathos and chilly beauty that the recording (released in 2004) quickly became my own personal benchmark for the work.

In a sense, though, it was inevitable that Bostridge would return to Winterreise in different company, as many of his predecessors have done (Fischer-Dieskau, for instance, recorded the work with nearly a dozen pianists); as he muses towards the end of his 2015 book Winter’s Journey: Anatomy of an Obsession, the idea of ‘endless repetition’ is hardwired into the cycle itself in that the final song sees the protagonist tentatively approaching a new accompanist with whom to repeat the whole sorry saga. Bostridge’s companion for this second journey is of course a far more distinguished and respected musician than the destitute old busker of Wilhelm Müller’s bleak final poem – the composer, conductor and pianist Thomas Adès, for whom he created the role of Caliban in The Tempest, and indeed there’s something of Shakespeare’s apparently monstrous outsider in the character they bring to life together here.

So what fresh insights has Bostridge uncovered in the intervening years? Short answer: plenty. One of the remarkable things about this new reading is just how much of the extensive scholarly work which both he and Adès have undertaken translates readily into sound: Bostridge, for instance, spends much of the early chapters of Anatomy of an Obsession exploring the idea of the protagonist as unreliable narrator, and whilst this may sound unduly academic on paper it comes across loud and clear on the recording. From the outset this wanderer is perceptibly less simpatico, more disingenuous than his earlier incarnation: instead of a greenhorn experiencing heartbreak for the first time, the impression is of an older, embittered man who’s spent years re-playing this story in his head and occasionally tweaking it to garner sympathy from his imagined audience. Throughout, there’s the sense of re-opening old wounds rather than smarting from recent ones, though the pain is if anything more immediate; it helps that the voice itself is rougher round the edges than it was in 2004, and that Bostridge takes more overt expressive risks these days, though there’s still some hypnotically beautiful singing in songs like Das Wirthaus and an eerily elongated Die Krähe (taken almost twice as slow as on the recording with Andsnes).

So what fresh insights has Bostridge uncovered in the intervening years? Short answer: plenty. One of the remarkable things about this new reading is just how much of the extensive scholarly work which both he and Adès have undertaken translates readily into sound: Bostridge, for instance, spends much of the early chapters of Anatomy of an Obsession exploring the idea of the protagonist as unreliable narrator, and whilst this may sound unduly academic on paper it comes across loud and clear on the recording. From the outset this wanderer is perceptibly less simpatico, more disingenuous than his earlier incarnation: instead of a greenhorn experiencing heartbreak for the first time, the impression is of an older, embittered man who’s spent years re-playing this story in his head and occasionally tweaking it to garner sympathy from his imagined audience. Throughout, there’s the sense of re-opening old wounds rather than smarting from recent ones, though the pain is if anything more immediate; it helps that the voice itself is rougher round the edges than it was in 2004, and that Bostridge takes more overt expressive risks these days, though there’s still some hypnotically beautiful singing in songs like Das Wirthaus and an eerily elongated Die Krähe (taken almost twice as slow as on the recording with Andsnes).

Adès, too, has done much homework on the various editions of the score, and his playing has such clarity that every detail registers: staccatos where we’re used to hearing slurs, dynamic shifts in slightly different places, and appoggiaturas which are usually glossed over all make their presence felt, as do the unsettling cross-rhythms as the post-van rattles its way into town more unsteadily than on most recordings. Much of the overall magic derives from Adès’s willingness to play straight man to Bostridge’s more Expressionist protagonist: if the singer flirts with Sprechstimme in places (perhaps inspired by his performances of Hans Zender’s ‘composed interpretation’ of the piece several years ago), Adès’s playing put me in mind of András Schiff’s recent Schubert recordings, and some of the colours he draws from the Wigmore’s Steinway sound for all the world like they emanate from a Brodmann or Érard. As with Bostridge’s endlessly illuminating, enriching book on the subject, the balance between pointing up the work’s strange modernity and engaging with its historical context is immaculately judged, and much of the beauty of the interpretation stems from the contrast between the two.

Adès, too, has done much homework on the various editions of the score, and his playing has such clarity that every detail registers: staccatos where we’re used to hearing slurs, dynamic shifts in slightly different places, and appoggiaturas which are usually glossed over all make their presence felt, as do the unsettling cross-rhythms as the post-van rattles its way into town more unsteadily than on most recordings. Much of the overall magic derives from Adès’s willingness to play straight man to Bostridge’s more Expressionist protagonist: if the singer flirts with Sprechstimme in places (perhaps inspired by his performances of Hans Zender’s ‘composed interpretation’ of the piece several years ago), Adès’s playing put me in mind of András Schiff’s recent Schubert recordings, and some of the colours he draws from the Wigmore’s Steinway sound for all the world like they emanate from a Brodmann or Érard. As with Bostridge’s endlessly illuminating, enriching book on the subject, the balance between pointing up the work’s strange modernity and engaging with its historical context is immaculately judged, and much of the beauty of the interpretation stems from the contrast between the two.

The biggest surprise, though, comes at the beginning of the final song: instead of the bare open fifth which usually announces the presence of the ghostly hurdy-gurdy man, we get a jarringly dissonant chord which I’ve never come across before on disc or in print. The effect is profoundly uncanny, and I’d love to know its provenance…

Postscript: Pentatone's UK distributor, RSK, very kindly contacted Thomas Adès to answer my final question shortly after the article was published: his answer is reproduced below.

'What I think Schubert is trying to notate with that appoggiatura at the start of Der Leiermann is the "tuning up" effect that you might get with a hurdy-gurdy, as the drone scoops up to the note. It is supposed to suggest instability and "poor" intonation, a "poor" quality of instrumental sound. I found that playing the grace note virtually (though not quite) simultaneously with the downbeat, and releasing it gradually into the fifth, obtains the closest illusion of this effect that a piano can achieve.'

Ian Bostridge (tenor), Thomas Adès (piano)

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC

Ian Bostridge

Available Format: Book

Ian Bostridge (tenor), Leif Ove Andsnes (piano)

Available Formats: MP3, FLAC

Schubert Lieder (3CDs & DVD)

Ian Bostridge (tenor), with Mitsuko Uchida (piano), with Leif Ove Andsnes (piano), with Antonio Pappano (piano)

As well as Bostridge's earlier Winterreise with Andsnes, Schwanengesang and Die schöne Müllerin, this set includes the DVD of David Alden's 1994 film of Winterreise with Bostridge and Julius Drake and an accompanying documentary, Over the Top With Franz.

Available Format: 3 CDs + DVD Video