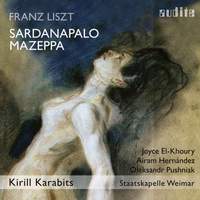

Recording of the Week,

Kirill Karabits conducts the world premiere of Liszt's Sardanapalo

I’ve received some sceptical looks over the past few weeks when I mentioned to friends that I was immersing myself in a Liszt opera, albeit an incomplete one – dating from around 1850, the composer’s projected setting of Byron’s Sardanapalus has been little more than a footnote in the history-books for almost 180 years, but last summer its existing single act was heard for the first time ever in Weimar thanks to painstaking reconstruction by Cambridge-based musicologist David Trippett.

The genesis and eventual abandonment of the project makes for a compelling story in its own right: Liszt never knew the identity of his librettist, whom evidence suggests was an Italian activist imprisoned for machinations against the Hapsburgs. Factor in an exiled Italian princess acting as intermediary plus the complex dynamics between Liszt and his son-in-law Wagner, and you have all the raw material for a sensational novel (or, as an eminent composer mused to me recently, perhaps another opera…).

The genesis and eventual abandonment of the project makes for a compelling story in its own right: Liszt never knew the identity of his librettist, whom evidence suggests was an Italian activist imprisoned for machinations against the Hapsburgs. Factor in an exiled Italian princess acting as intermediary plus the complex dynamics between Liszt and his son-in-law Wagner, and you have all the raw material for a sensational novel (or, as an eminent composer mused to me recently, perhaps another opera…).

You can read more about Sardanapalo’s complex back-story here, but my mission today is to talk about the proof of the pudding – does the existing act reveal an individual operatic voice which was never heard in full cry, or was Liszt’s decision to walk away and focus his energies on symphonic poetry a shrewd one?

The score is a fascinating, at times disconcerting melange of Italianate and Germanic elements, with long stretches of bel canto melody punctuated by darker, proto-Wagnerian outbursts and seasoned with harmonic shifts and orchestral colours which look towards Tristan und Isolde even as Liszt keeps one foot firmly anchored in the world of Bellini and Donizetti. After a shimmering Prelude that recalls Mendelssohn’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, we get a solid ten minutes of what sounds like early Verdi as the members of the Assyrian emperor Sardanapalo’s harem console the homesick favourite courtesan Mirra in music that wouldn’t sound out of place in La traviata or Don Carlo (both of these operas were just around the corner at this point, though Verdi already had Macbeth, Nabucco and Ernani under his belt).

With Mirra’s first declamatory utterance, though, we get the first hint that we’re not in Kansas anymore: the orchestration suddenly switches gears and the musical language becomes more chromatic, all of which plays out to great effect in an extended scena which fuses the vocal pyrotechnics of a Norma or Leonora with the sound-world of Elsa’s Dream in Lohengrin. (Liszt was preparing to conduct the premiere of that work at Weimar whilst working on Sardanapalo, so it’s no great surprise to hear whispers of Wagner’s swan-knight here, or echoes of Brabantian fanfares as the Assyrian army prepare for battle at the very end of the act).

The Lebanese-Canadian soprano Joyce El-Khoury does a valiant job, though there’s no disguising that Liszt wasn’t terribly accustomed to writing for the operatic voice and never got to the stage of trying things out with living, breathing singers – as with Beethoven’s Fidelio, the vocal writing often seems fundamentally instrumental in nature, in contrast with the bespoke tailoring provided by seasoned stage-animals like Donizetti or Rossini.

With Mirra’s first declamatory utterance, though, we get the first hint that we’re not in Kansas anymore: the orchestration suddenly switches gears and the musical language becomes more chromatic, all of which plays out to great effect in an extended scena which fuses the vocal pyrotechnics of a Norma or Leonora with the sound-world of Elsa’s Dream in Lohengrin. (Liszt was preparing to conduct the premiere of that work at Weimar whilst working on Sardanapalo, so it’s no great surprise to hear whispers of Wagner’s swan-knight here, or echoes of Brabantian fanfares as the Assyrian army prepare for battle at the very end of the act).

The Lebanese-Canadian soprano Joyce El-Khoury does a valiant job, though there’s no disguising that Liszt wasn’t terribly accustomed to writing for the operatic voice and never got to the stage of trying things out with living, breathing singers – as with Beethoven’s Fidelio, the vocal writing often seems fundamentally instrumental in nature, in contrast with the bespoke tailoring provided by seasoned stage-animals like Donizetti or Rossini.

The first appearance of the eponymous emperor (Canarian tenor Airam Hernández, singing with an open-throated ardour reminiscent of the young Pavarotti) manifests in a soaring love-duet that begins formulaically enough but transitions into what sounds like an early draft of Act II of Tristan, and the entry of the Machiavellian counsellor Beleso bringing news of an uprising is accompanied by portentous brass which anticipate both Verdi’s Fiesco in Simon Boccanegra and the baleful territory of Wagner’s Telramund and Hunding. Kirill Karabits and the Weimar Staatskapelle are on especially involving form in these last few minutes, and the act ends on a superb orchestral cliff-hanger as Sardanapalo’s troops march off to death or glory. It’s undeniably thrilling stuff, and by this stage I found myself so caught up in the drama that I was itching to crack on with the next four acts…until I remembered that they’d never materialised. Sardanapalo may be ‘the claw of a lion’ rather than the entire majestic beast (to borrow a phrase from one of Wagner’s letters to Liszt), but it’s definitely worth a visit.

(Please note that this recording does not include a libretto and translation, though both can be accessed online here.)

Joyce El-Khoury (Mirra), Airam Hernández (Sardanapalo), Oleksandr Pushniak (Beleso)

Weimar Staatskapelle, Kirill Karabits

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC