Recording of the Week,

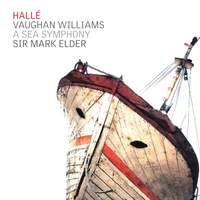

Mark Elder conducts Vaughan Williams' Sea Symphony

Vaughan Williams’ nine symphonies are surely among the greatest musical achievements to come out of Western Europe in the 20th century, and the Hallé under Mark Elder are arguably the finest contemporary interpreters of his music – worthy heirs to the great Vernon Handley and Richard Hickox. I was therefore quite excited to be able to hear their take on Vaughan Williams’ very first symphony, the work out of which his other orchestral compositions grew and developed over the decades.

It’s a work in which, while a unique personal voice is already present and establishing itself, nevertheless Vaughan Williams is clearly very much in the shadow of his teachers and those who influenced him. At one moment a jollity reminiscent of Stanford’s Songs of the Fleet comes to the fore to accompany imagery of flags and nations, and the busy bustle of a port or a ship underway is audible – while at the next, the music may take a philosophical turn, always steered by Walt Whitman’s words. These, indeed, were sources of inspiration for many composers writing at this time (one need only think of Arthur Bliss’ great choral ode, Morning Heroes, which seems at times rather to resemble this symphony). The first movement also incorporates achingly elegiac moments evoking Elgar’s Spirit of England and Music Makers, as the music makes moving – and, I couldn’t help feeling, poignantly timely – reference to “all that went down doing their duty”.

The Sea Symphony clearly and audibly sits at a musical crossroads – by this time, Vaughan Williams had already begun the studies with Ravel that would lead him to move in an almost Impressionistic direction, and that French, watercolour influence is just as palpable as the musical Englishness and Britishness that Vaughan Williams grew up with. Touches of the non-functional harmony that would become a cornerstone of Vaughan Williams’ style open the hauntingly beautiful Largo (an introduction that is mirrored in several of his later symphonies’ slow movements), and similar harmonies colour the music at many other points.

In the Largo, Whitman and Vaughan Williams are both at their most pensive – Roderick Williams’ inimitably rich, warm baritone unfolds a strongly universal message about the interrelatedness of “All souls, all living bodies though they be ever so different, / All nations, / All identities that have existed or may exist.” The mighty sound of Mark Elder’s multiple combined choirs (the Hallé Choir and Youth Choir, the Schola Cantorum of Oxford and Manchester’s Ad Solem all joining forces) leads the music to an uplifting climax before the movement closes in more subdued mood. Their diction is notably clearer than one often hears – this work can get quite orchestrally busy at times, and the singers often have their work cut out for them to get Whitman’s words across over the rolling waves of instrumental scoring.

The text moves in a decidedly spiritual direction in the final movement, with the imagery of the soul as a mariner on a ship expanded and developed. Both baritone and soprano soloists sing of the endless lure of exploration, both literal and metaphorical. Elder’s soprano soloist here is Katherine Broderick, a relative newcomer who I think we will and should be hearing much more of in years to come. Although she has relatively few recordings to her name so far (a couple of appearances in Elder’s Ring cycle, for example), she has already won a slew of awards, and her rich yet youthful voice is the perfect fit for this work. Her finest moment, for me, comes almost at the very end of the whole work – just as the chorus and orchestra seem to be driving towards a rousing final exhortation, a subito piano led by the soprano (with Vaughan Williams once again in quietly stirring Elgarian mode) provides instead a final glimpse of introspection. A last subtle hint of Debussy-esque waves, and the choir’s simple rocking motif sails over the horizon into silence – “Farther, farther, farther sail!”

In all this, I have been determinedly steering clear (sorry) of nautical similes about Mark Elder’s hand being “firmly on the tiller” and so on, but his pacing and control really are worth remarking on. This is a piece where pacing can make all the difference between a successful, uplifting performance and a tiresome one. The Sea Symphony is a big, big work, with some of the longest individual movements in the symphonic repertoire; judging the tempi on such a lengthy musical journey is no small task, and Elder’s account is to be praised for the way he avoids either flagging or rushing. A masterclass in choral symphonic music-making and conducting, and almost certainly one of my favourite discs of the year!

Katherine Broderick (soprano), Roderick Williams (baritone), Hallé Choir, Hallé, Mark Elder

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC