Interview,

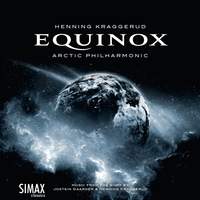

Henning Kraggerud's Equinox

Henning Kraggerud is an example of that rarest of musical beasts, the performer-composer. Both a writer of music and a proficient violinist, he walks in the spiritual footsteps of Chopin, Paganini, Rachmaninov and others who combined both musical roles with great success.

Henning Kraggerud is an example of that rarest of musical beasts, the performer-composer. Both a writer of music and a proficient violinist, he walks in the spiritual footsteps of Chopin, Paganini, Rachmaninov and others who combined both musical roles with great success.

And, indeed, of Vivaldi and Bach - his latest composition, Equinox, takes a similar starting-point to the famous Four Seasons and the Well-Tempered Clavier, but with a global perspective. Consisting of four concertos for four times of day, it is broken down into 24 movements that mirror the hours, the Earth's time-zones and of course the musical keys, all tied together with a moving narrative penned by best-selling author Jostein Gaarder.

I asked Henning about the thinking behind this complex and deeply fascinating project.

Much has been written about the properties of different keys – Rimsky Korsakov and Scriabin are just two of the most famous composers to set down their thoughts on the characteristics of the keys of Western classical music. Do you think the “personalities” we ascribe to keys are really innate to the keys themselves in some way – perhaps subtleties of pitches, frequencies or intervals – or are they “in the eye of the beholder”, merely projected onto them by us as listeners?

This is a very complex question to answer. Certainly in the old days different tuning systems gave the various keys particular characteristics, especially for keyboard instruments, but even today the keys are affected by open strings or stopped notes on string instruments. In addition, since written music is interpreted by human players the notation itself greatly contributes to how the musicians perform the music. If you were to notate one piece in both G-flat major and F-sharp major a computer program would play the versions identically - but I am quite sure that real musicians would play them very differently. If faced just with the notes, and without tempo or dynamic markings I am still certain that musicians would give a mellower, slower, softer and possibly more cantilena interpretation of the six-flat version than its enharmonic equivalent. This would make an interesting experiment, if it hasn't been done already!

Beethoven said it was a crime when a soprano transposed a Mozart aria - he said that if she couldn't sing it in the original key she should refrain from singing it altogether. When he was confronted with the argument that concert pitch itself had risen during past decades he replied that this was irrelevant since people's feelings about the keys rose along with the pitch. So when early musicians sometimes perform his Symphony No. 5 in what sounds to us like B minor they actually disobey Beethoven's own directions.

Within the framework of a work connected to 24 keys and 24 time-zones, there’s still quite a lot of room for different decisions to be made. What made you head “down” into the flat keys first, rather than “up” towards G, D, A major? And is it connected to your decision to travel East first, rather than West?

Jostein Gaarder and I decided to travel eastwards so that even having covered 24 hours and 24 time zones - each location one hour further on from Greenwich - we could still arrive back in Greenwich at the same time as we left! It wouldn't have been possible to have maintained the same time all over the world by going westwards.

As for the direction of the 'circle of fifths', I wanted to move from six flats (E-flat minor) to six sharps (F-sharp major) as we crossed the dateline at midnight. Since I wanted it all to start in C major, I went directly from there to D minor and saved A minor for the last postlude, in Iceland. We could have gone the other way around the circle of fifths of course, but I happen to like modulations down a fifth much more than upwards, and I also felt this suited our eastern journey. This order also makes it possible to start and end each concerto on the same tonic - for example the first concerto begins in C major and ends in C minor

Similarly, what is the significance of the choices of locations around the world? Do they relate closely to the keys of their movements – for example, what binds Prague and the key of D minor together? And doesn’t the sequence of keys risk forcing the narrative into a certain emotional shape?

I think the sequence of keys certainly shapes the narrative emotionally - 'force' is too strong a word though. This project started out when I invited myself for coffee with Jostein Gaarder a few years ago now (we first met back in 1992 before he became world-famous) and I took along the fascinating book A History of Key Characteristics in the 18th and Early 19th Centuries by Rita Steblin. This discusses all known theories about the keys up to the mid-1800s, which were regarded as a sort of 'quasi-science' like astrology. These theories were long before Scriabin and Rimsky-Korsakov's, which we disregarded for this project. Of course all the theorists, composers and philosophers of those early days did not agree, so we just chose the ideas we thought most fitting with our own vision for Equinox.

Why 24 Postludes, rather than more conventionally-titled concerto movements? Postludes to what?

I decided that it worked best for the music to develop threads from Jostein's storylines in Equinox, so when the work is performed in its entirety - music and text - each musical movement follows a passage of text. I therefore modified my original idea of writing 24 'preludes' to 24 'postludes'. Also, these pieces can be used individually as encores and the name 'postlude' seemed fitting for that purpose as well.

Your collaboration with the author Jostein Gaarder on this project is a fascinating cross-pollination between the worlds of literature and music; how closely did you work together as the work (or works) took shape – and did you find his input led the music in directions you hadn’t originally expected?

We collaborated very closely from the start, beginning with extensive discussions about our feelings towards different keys and also how we could develop ancient ideas about the keys artistically. Then Jostein went to Greenwich on the day of Equinox itself and at his hotel there he drafted the synopsis and recorded the exact weather at each location around the world at the moment of the Equinox. His story is multi-layered, taking part in both the present time and also that of the quotes by which we were inspired. These different time periods inspired the music too. As we move away from C major theories about the keys get weirder and weirder, and this is reflected both in the text and music.

Once Jostein had delivered the whole manuscript to me I began to compose. Hence I was inspired by the historical quotes about the keys, the places Jostein had chosen, and his text itself - the psychological drama of the main character awaiting diagnosis of a serious disease, his romantic meeting with a woman in Greenwich, and his 'magical' travel as he is thrown around the globe. There's also a historical narrative charting how Coordinated Universal Time came about and more.

My postludes were definitely hugely influenced by Jostein's text but I also intended them to work on their own, and I regularly perform the music both with and without the text. I would also like to explore possibilities to collaborate with other art forms for Equinox - dance for example. And I have a dream of performing all the pieces at their respective locations around the world - but that's a serious undertaking and would require some sponsorship! I'm currently working on a violin/piano version with Nils Thore Røst so that should make some of the more remote locations like Greenland a possibility.

Down the ages, there have been plenty of works representing the times of day, seasons of the year etc., as well as of course those traversing all 24 keys. Bach, Vivaldi, Haydn, Tchaikovsky, Shostakovich, Piazzolla… Did you draw inspiration from any of these works in particular when writing yours?

I was always envious of keyboard players' abundant choice of collections in all 24 keys and really wanted to create one for violin. The only violin set I knew about was Pierre Rode's 24 Caprices, and although they're rather nice they are mainly used as studies and seldom performed in concerts. So Bach and Chopin's keyboard collections were an early inspiration for the form of Equinox.

The decision to arrange the postludes into the four concertos 'Afternoon', 'Evening', 'Night' and 'Morning' was inspired mainly by Vivaldi's Four Seasons, though of course I was aware of both Haydn's 'Morning', 'Midday' and 'Evening' symphonies and his oratorio The Seasons.

Jostein introduces a new character to us at each time-meridian, but since those 24 meridians cross the poles and form 12 circles, we meet each character twice. We are then half a world and half an octave (a tritone) away from where we first met the character. So I also paired these postludes as variations - numbers 1 and 13, 2 and 14 etc share some important properties. Since Jostein Gaarder ends his text with an Overture I decided to conclude with a final 25th movement, an Overture in C. Overture to what? Well that's the question!

Equinox is out on Simax this Friday.

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC